Asma al-Assad looks poised and fragrant as she ladles food out of a vast silvery bowl to children who wait patiently for their portion. The first lady of Syria is dressed down for the occasion in a pale blue blouse, caught in an ethereal white light as she tends to the needs of her people. The woman is a saint.

In another photograph she sits on the ground with girls in Guide-like uniforms, and in another, she gives a little girl a new doll. She chats and smiles with grateful (and perhaps nervous) recipients of her bounty, in touchy-feely pictures that show her physically touching the poor and disabled.

These are some of the images from the daily rounds of the wife of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad that are puzzling a world riven by debate about claims that al-Assad used sarin gas in an attack on his people in the suburbs of Damascus on Aug. 21. While the Syrian regime’s responsibility for the attack is disputed by Russia, China, British Leader of the Opposition Ed Miliband and many more who refuse to accept US accusations at face value, reactions to these photographs have been pretty much a universal “ugh.” From Israel’s Haaretz to Britain’s Daily Mail, the bland, Hello-like images of Asma al-Assad posing with little conviction as a friend of the people while her husband’s civil war with rebels is devastating the country seem to strike most observers as “shameless” and grotesque.

The smiling, sun-kissed world of the al-Assads — while she does charity work, he holds decorous meetings with dignitaries — come from the Syrian presidency’s Instagram account. The hugely popular photography Web site and app allows users to display and share pictures in a visually seductive way. You can see the temptation for Bashar al-Assad to use this benign tool for propaganda. However, his Instagram smilorama appears to be backfiring: while argument rages over his alleged use of poison gas, his Instagram is drawing sneers. Perhaps the UN could even agree to condemn its bad taste.

It’s no laughing matter. In a curious way, these pictures of Asma al-Assad reveal the truth about Syria. Their blatant phoney quality — the first lady serving hot lunches while in reality al-Assad’s forces have been accused of targeting bakeries, and refugees are streaming hungry for the borders — allows us to recognize the embattled Syrian regime for what it is. They stir a sinister sense of recognition, for who has not heard of the banality of evil?

The war in Syria has been made easier for Bashar al-Assad by powerfully enforced reporting restrictions. The death of the renowned war reporter Marie Colvin in Homs in February last year sent out a powerful message (it is unclear whether she and the other reporters killed or injured with her were deliberately targeted) about how hard it would be to get the truth from this killing zone. Many images of horror have come out of Syria since, but have to be examined carefully. Was a video that surfaced on YouTube early in the war, in which the cameraman observes a sniper at work until he is shot himself as the gun turns on him, an authentic piece of citizen reporting?

Reality has proved easy to destroy in Syria. Facts are hard to come by and have to be peered at through a bloody fog. The old adage that truth is the first casualty of war has never been more brutally proven — because Bashar al-Assad attacked truth from the start. As the civil war, we called it a rebellion then, started in 2011, he simply banned most foreign journalists from Syria. This is such a familiar fact it may seem obtuse to restate it. Yet it is no coincidence that two years into the conflict, international onlookers are debating fundamental issues of fact and evidence, with many people giving al-Assad the benefit of the doubt on last month’s chemical attack.

Amid this uneasy global debate, Bashar al-Assad’s Instagram comes as a luminous portrait of the ruler, his marriage and lifestyle. It is a glittering triumph of banality. The al-Assads really seem to believe that they are the perfect couple, the dashing man of power and his beautiful and gracious first lady.

It is too simplistic to describe these images as “propaganda.” Propaganda for whom? Can the regime really think pictures of Asma al-Assad meeting the people will efface dead bodies, blasted cities and homeless children? It can only appear monstrous to outsiders to see this myth of a sanitized Syria promoted by a government at war with a large part of its own people.

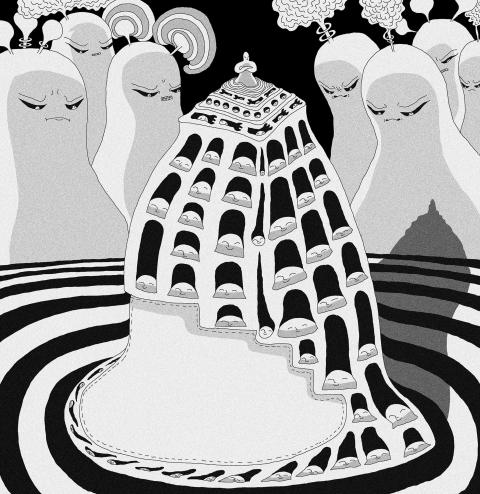

Yet the Syrian president must think the pictures have purchase, that he can smile his way to success — and this can only be because he and his supporters drug themselves with such images. Dictators don’t just fool the people. They fool themselves first. Dictators’ private lives are often kitsch fantasy worlds that enable a ruler to believe in a myth that is then projected outwards and buttressed by violence. The al-Assad Instagram world of glossy magazine glamor is just another such self-empowering fantasy.

It has something in common with the photo albums found when Libyans stormed then-leader Muammar Qaddafi’s family compound. Pictures of the dictator and his children posing with pet camels mingled with Qaddafi’s pictures of former US secretary of state Condoleezza Rice. These albums — like the desert-disco decor of the Qaddafi residences — were not intended for public consumption. They were not “propaganda.” The dictator himself liked to look at images of his private life that strengthened his sense of identity.

Adolf Hitler, similarly, worked on a private fantasy of who he was. He did not conduct his affair with Eva Braun in the public eye — her existence was a secret from most Germans. Yet plenty of photographs record their relationship and celebrate the leisure life of the Fuhrer in Bavaria and Berlin. Braun and his dog feature heavily in these eerie pictures. Both appear to have been props in his own self-image. Hitler’s real relationship with Braun is a mystery — observers said he was awkward in her company.

No one would doubt that the al-Assads have a “real” marriage — but what is real in the life of dictators? In the glory days of the Arab spring, the image of dictatorship as a corrupt, abusive form of rule was widely excoriated across the Middle East and in the west. It was easy for all parties to join in portraying Qaddafi as a tyrant reminiscent of Roman emperors Caligula or Nero. Today, so soon, disillusionment is such that even calling al-Assad a “dictator” may be seen as a caricature legitimating US aggression. However, the Instagram says it all. Here is a ruler just as deluded as Qaddafi, just as intoxicated with his own myth. To live in this false world is the nature of absolute rulers.

The ancient Romans knew that. Their historians describe with terse fury the madness of emperor Tiberius, hiding from the public gaze at his villa on Capri among his young sex slaves, and Nero, setting fire to Rome to clear land for a new palace.

In the 20th century, Hannah Arendt, witnessing the trial of SS lieutenant colonel Adolf Eichmann, one of the architects of the Holocaust, coined that phrase “the banality of evil” to describe the strange emptiness and unsatisfying lumpenness of history’s criminals. Al-Assad’s Instagram world is supremely banal. Rather than a Nero fiddling while Rome burns or a Hitler dreaming of architectural follies in his last days in the bunker, the Syrian president in these pictures just wants to come across as a great guy with a lovely wife. However, the space between these images and the stench of war is so manifest that it reveals a true dictator’s loss of touch with reality.

The smiling fantasy of Bashar al-Assad’s Instagram is blandly psychotic. It reveals a terrible gulf between reality and the ruler’s fictional self-image. Banality may not be in itself a proof of evil. However, in the psychology these pictures reveal, what lies are not possible? The mind that can believe in these pictures might easily order a war crime then go home to kiss his beloved wife.

The gutting of Voice of America (VOA) and Radio Free Asia (RFA) by US President Donald Trump’s administration poses a serious threat to the global voice of freedom, particularly for those living under authoritarian regimes such as China. The US — hailed as the model of liberal democracy — has the moral responsibility to uphold the values it champions. In undermining these institutions, the US risks diminishing its “soft power,” a pivotal pillar of its global influence. VOA Tibetan and RFA Tibetan played an enormous role in promoting the strong image of the US in and outside Tibet. On VOA Tibetan,

Sung Chien-liang (宋建樑), the leader of the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) efforts to recall Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) Legislator Lee Kun-cheng (李坤城), caused a national outrage and drew diplomatic condemnation on Tuesday after he arrived at the New Taipei City District Prosecutors’ Office dressed in a Nazi uniform. Sung performed a Nazi salute and carried a copy of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf as he arrived to be questioned over allegations of signature forgery in the recall petition. The KMT’s response to the incident has shown a striking lack of contrition and decency. Rather than apologizing and distancing itself from Sung’s actions,

US President Trump weighed into the state of America’s semiconductor manufacturing when he declared, “They [Taiwan] stole it from us. They took it from us, and I don’t blame them. I give them credit.” At a prior White House event President Trump hosted TSMC chairman C.C. Wei (魏哲家), head of the world’s largest and most advanced chip manufacturer, to announce a commitment to invest US$100 billion in America. The president then shifted his previously critical rhetoric on Taiwan and put off tariffs on its chips. Now we learn that the Trump Administration is conducting a “trade investigation” on semiconductors which

By now, most of Taiwan has heard Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an’s (蔣萬安) threats to initiate a vote of no confidence against the Cabinet. His rationale is that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP)-led government’s investigation into alleged signature forgery in the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) recall campaign constitutes “political persecution.” I sincerely hope he goes through with it. The opposition currently holds a majority in the Legislative Yuan, so the initiation of a no-confidence motion and its passage should be entirely within reach. If Chiang truly believes that the government is overreaching, abusing its power and targeting political opponents — then