Valdevaqueros is one of the last remaining unspoiled beaches in southern Spain, where kites hauling surfers along the waves dot the sky over golden sands buttressed by one of the country’s few shifting sand dunes.

Currently, the beach has little more than an access road lined with camper vans from Germany, France, Italy and Britain which disgorge windsurfers and kitesurfers lured by the area’s strong winds.

For decades, it has been a world apart from the concrete-lined beaches of Torremolinos and Marbella along the coast, yet on May 29, the local council in Tarifa, Andalusia, approved plans to build a tourist complex right next to the beach, with 1,400 hotel rooms and 350 apartments.

Environmental and conservation groups have protested that the project will harm the habitats of protected species, but for most councilors, the issue is simple: jobs. In this town of 18,000 inhabitants, 2,600 are out of work, as Spain faces its worst economic crisis in at least half a century, and one that has cast doubt on the future of the euro.

“Traditional sources of income such as fishing are dying out, now that fleets are being dismantled and fish stocks are depleted, so tourism is the only way out, as long as it is sustainable,” said Sebastian Galindo, a councilor from the Socialist Party, which is in opposition in Tarifa, but voted with the governing People’s Party to give the project the green light.

Tarifa Mayor Juan Andres Gil declined to comment on the project, but Galindo said it complies with environmental standards. The complex would be 800m from the coast, comfortably beyond the minimum of 200m stipulated in the landmark 1988 Coastal Law, drawn up to prevent more ugly developments that have blighted much of Spain’s coastline when mass tourism first descended on its shores in the 1960s and 1970s.

The site is also sandwiched between the Estrecho and Alcornocales national parks, but encroaches on neither, Galindo said.

He vowed to check developments closely, but admitted that the project may not get off the drawing board “in the current economic climate.”

Just meters from the corner cafe where Galindo spoke, idle cranes loom over blocks of apartments that have lain unfinished or empty since a property bubble burst in 2008, swiftly turning Spain from the eurozone’s fastest-growing economy into one that may soon need a European bailout to help rescue its parlous public finances.

Opponents of the complex say the last thing anyone needs is more housing in a country that already has a million empty homes, although the central government last week proposed a sell-off by granting non-Spaniards residency permits in return for buying property worth at least 160,000 euros (US$206,700).

The Socialist opposition in Madrid slammed the proposal and Galindo said it discriminated against migrant workers who flocked to Spain during the boom years, many of them from Morocco, whose coastline is just 14km away and can be seen from Tarifa.

“It favors moneyed classes rather than those who came here to help Spain get ahead,” he said.

Surfers such as Henning Mayer fear that new buildings in Valdevaqueros would sap the strength of the famous local Levant wind, but fail to lure traditional package holidaymakers.

“It’s not really a family spot. Just wait until they see what a Levant is like,” said Mayer, who has regularly made the journey from Augsburg in Germany for 20 years. “Ten years ago they said they would build a new highway here. It didn’t happen, so I think it will be impossible to build new hotels.”

Perched on the southernmost tip of Spain, Tarifa is at the strategic crossroads between Africa and Europe, where the Mediterranean Sea meets the Atlantic. Campaigners say it also has a vital role in the animal world as a crossroads for migrating species.

Salvemos Valdevaqueros (“Let’s Save Valdevaqueros”) became a trending topic on Twitter 12 hours after the Tarifa council voted for the project.

The campaign also has a Facebook page and is supported by groups including Greenpeace, the World Wide Fund for Nature and the Spanish branch of conservation network Birdlife, as well as Spain’s indignado movement, which arose last year to protest against a political system that they say denies people a voice in deciding how to face the crisis.

“It’s the environmental equivalent of putting a shopping center right in the middle of the Alhambra,” said Noelia Jurado, 38, who uses the multimedia expertise she gained while running an advertising agency in nearby Algeciras to campaign against the complex.

She added that the resort would be near the ancient Roman town of Baelo Claudia.

“They could be building on top of more Roman ruins here. Nobody knows,” she said.

Also joining the charge against the planned resort has been the Andalusian College of Geographers, which in a preliminary study charted on its Web site concluded that “free areas,” including car parks if not actual buildings, will overlap part of the Alcornocales national park.

The geographers also estimate that the site intrudes on two areas designated by the European Environmental Agency as part of its Natura 2000 network of conservation zones to protect wildlife across the EU. One of the areas in Valdevaqueros is home to the lesser mouse-eared bat and the greater horseshoe bat, both species whose survival is threatened.

Environmental group Ecologistas en Accion (“Ecologists in Action”) asked the EU in June to take legal action against the Valdevaqueros project because of the conservation risks.

“Money is once again being put before urban laws and European environmental directives,” said Raul Romeva, a member of the European Parliament who is vice president of the Greens group. “European public interest in the Natura 2000 network is neither being applied nor safeguarded.”

In Romeva’s view, the project is also at fault because the proposed site has too little water in a town that already suffers from shortages in the summer weather that scorches the southern Spanish region of Andalusia.

Lack of water led the Andalusia supreme court last month to uphold an appeal filed by Ecologistas en Accion in 2005 against plans to build a complex called Merinos Norte elsewhere in the region, which would have included golf courses, hotels and luxury homes.

Many locals are also wondering why a resort should be built 10km away, rather than on wasteland near Tarifa’s picturesque old center, with its typically Andalusian whitewashed walls and winding streets, dominated by a 10th-century Moorish castle.

“My opinion and that of catering workers is that we agree [with the complex] as long as it creates jobs in the town, which is what is needed, but we are against it being for the benefit of a few,” said Cristobal Lobato, 45, who has waited on tables at the same beachside bar in Tarifa for 30 years.

“If they put it in the center of Tarifa, where there is space, then clients could visit shops, tapas bars and restaurants,” he said.

Overlooking the green fields earmarked for building, biologist Aitor Galan, 41, who conducts environmental impact studies for a living, pointed at one of only two seaside breeding grounds for vultures in Europe.

“Anywhere else in Europe, this place would have the utmost protection, but here they want to get rid of it all and cover it with buildings,” he said, while peering through binoculars. “What they want to do is turn this into Benidorm, but what draws people here is wildlife and the wind.”

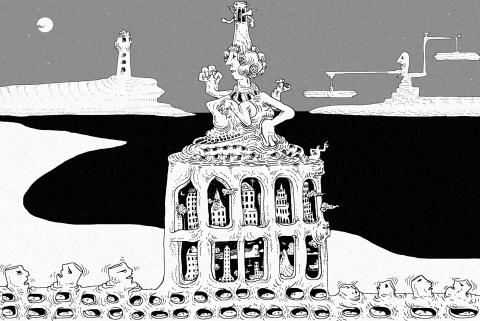

They did it again. For the whole world to see: an image of a Taiwan flag crushed by an industrial press, and the horrifying warning that “it’s closer than you think.” All with the seal of authenticity that only a reputable international media outlet can give. The Economist turned what looks like a pastiche of a poster for a grim horror movie into a truth everyone can digest, accept, and use to support exactly the opinion China wants you to have: It is over and done, Taiwan is doomed. Four years after inaccurately naming Taiwan the most dangerous place on

Wherever one looks, the United States is ceding ground to China. From foreign aid to foreign trade, and from reorganizations to organizational guidance, the Trump administration has embarked on a stunning effort to hobble itself in grappling with what his own secretary of state calls “the most potent and dangerous near-peer adversary this nation has ever confronted.” The problems start at the Department of State. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has asserted that “it’s not normal for the world to simply have a unipolar power” and that the world has returned to multipolarity, with “multi-great powers in different parts of the

President William Lai (賴清德) recently attended an event in Taipei marking the end of World War II in Europe, emphasizing in his speech: “Using force to invade another country is an unjust act and will ultimately fail.” In just a few words, he captured the core values of the postwar international order and reminded us again: History is not just for reflection, but serves as a warning for the present. From a broad historical perspective, his statement carries weight. For centuries, international relations operated under the law of the jungle — where the strong dominated and the weak were constrained. That

The Executive Yuan recently revised a page of its Web site on ethnic groups in Taiwan, replacing the term “Han” (漢族) with “the rest of the population.” The page, which was updated on March 24, describes the composition of Taiwan’s registered households as indigenous (2.5 percent), foreign origin (1.2 percent) and the rest of the population (96.2 percent). The change was picked up by a social media user and amplified by local media, sparking heated discussion over the weekend. The pan-blue and pro-China camp called it a politically motivated desinicization attempt to obscure the Han Chinese ethnicity of most Taiwanese.