The question that dashed Angel Feng’s job prospects always came last.

Fluent in Chinese, English, French and Japanese, Feng, a 26-year-old business school graduate, interviewed with a half-dozen companies in Beijing this year, hoping for her first job in the private sector, where the salaries are highest.

“The boss would ask several questions about my qualifications, then he’d say: ‘I see you just got married. When will you have a baby?’” Feng recalled. “I’d say not for five years, at least, but they didn’t believe me.”

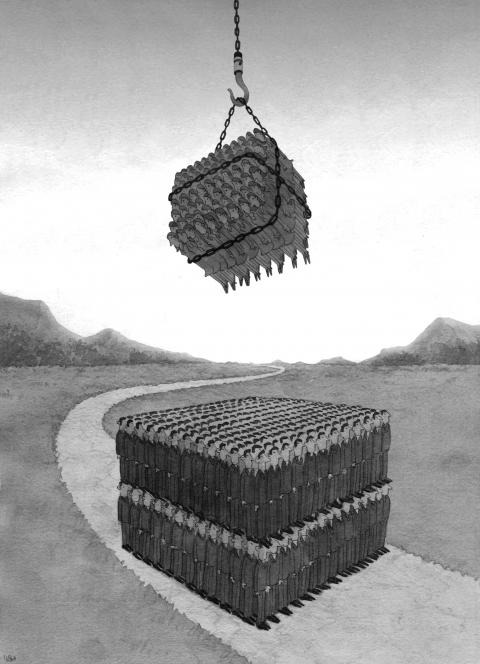

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

Turned down again and again, she took a job at “a really bad place,” then quit. Finally she ended up at a “semi-state” organization run by the Ministry of Education. The pay is lower, but she gets benefits that hark back to the socialist days, including at least 90 days of maternity leave at full pay.

The difference says everything about the mixed challenges facing women in China’s hybrid economy three decades after it embarked on dazzling economic reforms. Women today no doubt have more freedom to choose their paths, but the expanding private sector is not always welcoming.

As socialist-era structures shrink, the powerful cultural traditions that value men over women — long held in abeyance by official Chinese Communist Party support for women’s rights — have returned in force.

Many employers are choosing not to hire women in an economy where there is an oversupply of labor and where women are perceived as bringing additional expense in the form of maternity leave and childbirth costs. The law stipulates that employers must help cover those costs, and feminists are seeking a system of state-supported childbirth insurance to lessen discrimination.

The result is that even highly qualified candidates like Feng can struggle to find a footing. After her series of rejections, Feng finally found work at a company that promoted Chinese brands. It was hardly her first choice.

The hours were long, and a colleague who suffered a late miscarriage was ordered back to work within three days. Her salary was about US$745 a month, without benefits.

She quit in July for a job with the China Education Association for International Exchange. The pay is lower, about US$625 a month, but she gets a housing allowance and at least her employer does not object to employees having babies.

The job may be “a bit boring,” she said, but for now, she, like others, has made her choice.

Guo Jianmei (郭建梅), director of the Beijing Zhongze Women’s Legal Counseling and Service Center, insists that, overall, women today are in a better position than they were three decades ago.

“They know so much more about their rights,” she said. “They are better educated. For those with a competitive spirit, there’s a world of opportunity here now, whether they are businesswomen, scientists, farmers or even political leaders. There really have been huge changes.”

Practical concerns about coping in a highly competitive world are also feeding into a powerful identity crisis among China’s women.

“The main issue we face is confusion, about who we are and what we should be,” said Qin Liwen, a magazine columnist. “Should I be a ‘strong woman’ and make money and have a career, maybe grow rich, but risk not finding a husband or having a child?”

“Or should I marry and be a stay-at-home housewife, support my husband and educate my child? Or, should I be a ‘fox’ — the kind of woman who marries a rich man, drives around in a BMW, but has to put up with his concubines?” she said.

Feng Yuan (馮媛), director of the Center for Women’s Studies at Shantou University, said many women were deciding to opt out of the private sector.

“The state sector is quite popular with women because their rights are better protected there,” she said.

At least on paper, women’s rights are supposed to be well protected. In 2005, the government amended the landmark 1992 Law on the Protection of Women’s Rights and Interests, known as the Women’s Constitution, to make gender equality an explicit state policy. It also outlawed, for the first time, sexual harassment.

Yet sex discrimination is widespread. Only a few women dare to sue employers for unfair hiring practices, dismissal on grounds of pregnancy or maternity leave, or sexual harassment, experts say. Employers commonly specify sex, age and physical appearance in job offers.

There are gaps in the law. A major problem, said Feng Yuan, who is not related to Angel Feng, is that it does not define sex discrimination.

The law also sticks to the longstanding requirement that women retire five years earlier than men at the same jobs, thereby reducing earnings and pensions.

In 2008, 67.5 percent of Chinese women over 15 were employed, said Yang Juhua of the Center for Population and Development Studies at Renmin University, citing World Bank statistics.

That was a drop from the most recent Chinese government data, from 2000, showing that 71.52 percent of women from 16 to 54 were employed, compared with 82.47 percent of men from 16 to 59. Yang has calculated that women earn 63.5 percent of men’s salaries, a drop from 64.8 in 2000.

And yet there are many stories of individual success, built on hard work — and some luck. Shi Zaihong’s is one.

Born into a poor rural family in Anhui Province, Shi, now 41, came to Beijing to work as a nanny in 1987. She earned about US$6 a month.

Today, she works 10 cleaning and child-minding jobs, earning about US$1,050 a month. With her husband, who runs a small business putting up advertisements, she bought an apartment just outside Beijing for about US$75,000 — an astonishing achievement for a migrant worker with just five years of education.

The mother of a 16-year-old son and a three-year-old daughter, Shi can now apply for her children to legally join her because buying property confers this right, she said.

Shi’s eyes shine as she talks about her accumulation of wealth, far outstripping what her mother was able to save as a farmer.

“I have taken advantage of every opportunity that I had, and I have always worked hard,” she said. “Things are good. Very good.”

Wherever one looks, the United States is ceding ground to China. From foreign aid to foreign trade, and from reorganizations to organizational guidance, the Trump administration has embarked on a stunning effort to hobble itself in grappling with what his own secretary of state calls “the most potent and dangerous near-peer adversary this nation has ever confronted.” The problems start at the Department of State. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has asserted that “it’s not normal for the world to simply have a unipolar power” and that the world has returned to multipolarity, with “multi-great powers in different parts of the

President William Lai (賴清德) recently attended an event in Taipei marking the end of World War II in Europe, emphasizing in his speech: “Using force to invade another country is an unjust act and will ultimately fail.” In just a few words, he captured the core values of the postwar international order and reminded us again: History is not just for reflection, but serves as a warning for the present. From a broad historical perspective, his statement carries weight. For centuries, international relations operated under the law of the jungle — where the strong dominated and the weak were constrained. That

The Executive Yuan recently revised a page of its Web site on ethnic groups in Taiwan, replacing the term “Han” (漢族) with “the rest of the population.” The page, which was updated on March 24, describes the composition of Taiwan’s registered households as indigenous (2.5 percent), foreign origin (1.2 percent) and the rest of the population (96.2 percent). The change was picked up by a social media user and amplified by local media, sparking heated discussion over the weekend. The pan-blue and pro-China camp called it a politically motivated desinicization attempt to obscure the Han Chinese ethnicity of most Taiwanese.

The Legislative Yuan passed an amendment on Friday last week to add four national holidays and make Workers’ Day a national holiday for all sectors — a move referred to as “four plus one.” The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), who used their combined legislative majority to push the bill through its third reading, claim the holidays were chosen based on their inherent significance and social relevance. However, in passing the amendment, they have stuck to the traditional mindset of taking a holiday just for the sake of it, failing to make good use of