“People were shot. We went there and found people lying all over the ground. But something amazing happened. There was a black cloud. For 15 minutes it rained heavily after the shooting. It washed all the blood … ”

Ikabot Makiti’s voice trails off into quiet sobs. The former student activist cannot forget the strewn corpses of men, women and children, or the mass burials that followed. Half a century has passed but memories of the Sharpeville massacre still run deep.

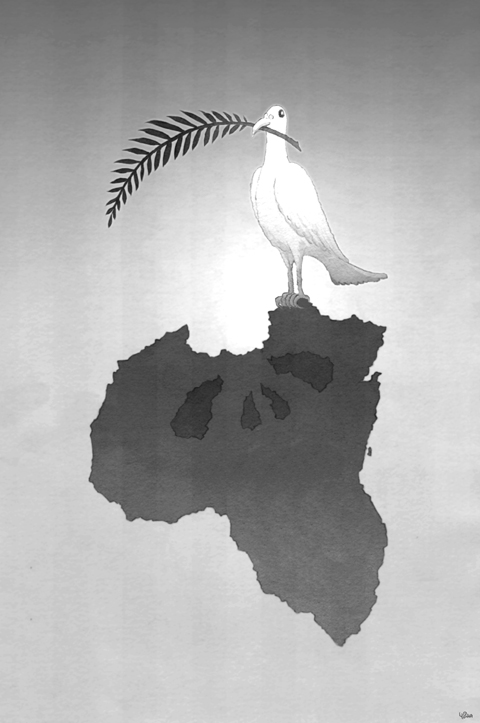

Yesterday marked the 50th anniversary of the day that changed the course of South African history. When police opened fire on thousands of unarmed protesters, killing 69 and injuring about 180, they inadvertently provided a catalyst for decades of armed struggle and forced the rest of the world to confront the iniquity of apartheid. White minority rule finally collapsed in 1994. Two years later, it was in Sharpeville that the country’s first black president, Nelson Mandela, signed a new Constitution.

Named after the Glaswegian immigrant John Lillie Sharp, Sharpeville is a township about 50km south of Johannesburg. Black people were forcibly relocated here and in 1960 it had only two tarred roads with electric lighting.

On March 21 that year, the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC), a breakaway organization from the African National Congress, mobilized black people across the country to demonstrate against laws that controlled their movement.

Thousands gathered outside the local police station in Sharpeville, challenging the police to arrest them for being without the pass books, or dompas, they were meant to produce on demand.

Makiti, who at the time was a 17-year-old PAC member, recalled that the demonstrators were in high spirits, holding umbrellas and throwing their hats in the air.

“There was jubilation around, not anything that suggested people were angry or wanting to fight,” said the grandfather, who later spent five years imprisoned on Robben Island. “They were waiting for the answer and the answer came with the bullet. I think the police just panicked because of the mob.”

Without warning, the police opened fire on the crowd. Most of those who died were shot in the back as they fled.

Piet Tshabalala, 86, recalled: “Something hit me on the leg and I saw blood. The pregnant woman next to me lay in a pool of blood after being shot in the stomach.”

The bullets hit another pregnant girl, 16-year-old Ziphora Mameho, but she survived.

“The people were demanding a response and the police started shooting. I ran for a few meters but was shot in the leg. The person I was running with died,” she said.

“The other guys commanded me to stay down because otherwise I’d be shot. I said I’d rather die because I didn’t have a leg to use. I remember an Afrikaner [white] policeman stopping and saying: ‘Now you’ve received the Africa you were fighting for,’” Mameho said.

Mameho, now 66, rolls down a sock to show uneven bones beneath her scarred skin. She spent 18 months in hospital, where doctors inserted her short rib in her leg, and she gave birth to a son, Samwell, without complications.

The anniversary is marked every year as Human Rights Day across South Africa. This year Deputy South African President Kgalema Motlanthe was scheduled to address a commemorative rally in Sharpeville.

But political freedom has not delivered economic freedom for its residents. The roads are potholed and some still lack tarmac, rubbish is strewn on wasteland and the stadium where Mandela signed the Constitution is run down. Unemployment is rife and two schools recently closed.

“Apartheid made us despair. Even though today our kids have better lives, we struggle,” Mameho said. “We suffer because of the hardships and we don’t have money for medical attention.”

Last month people took to the streets, burning tires in protest at poor service delivery, and once again the crack of police gunfire was heard in Sharpeville.

Hofni Mosesi, an executive of the Concerned Residents of Sharpeville, said: “It blurs the difference between the apartheid government and our government. We feel bitter about it if it happens today, if it’s done by the government we voted into power.”

He said while the ANC remembers Sharpeville on the anniversary, it is neglected for the other 364 days of the year.

“This township is just good as far as March 21 is concerned; otherwise, nothing else, forget about it,” he said.

Asked if he felt the sacrifices of 1960 had been in vain, Mosesi said: “To us, it was worth it. It could be that it’s not worth it to our present authorities, because if it was worth something, our township wouldn’t be in the state it’s in at the moment. The government has betrayed that legacy.

“At some stage all hell will break loose. We don’t know when. There will come a point when we say we have done everything in our power,” he said.

The gutting of Voice of America (VOA) and Radio Free Asia (RFA) by US President Donald Trump’s administration poses a serious threat to the global voice of freedom, particularly for those living under authoritarian regimes such as China. The US — hailed as the model of liberal democracy — has the moral responsibility to uphold the values it champions. In undermining these institutions, the US risks diminishing its “soft power,” a pivotal pillar of its global influence. VOA Tibetan and RFA Tibetan played an enormous role in promoting the strong image of the US in and outside Tibet. On VOA Tibetan,

Former minister of culture Lung Ying-tai (龍應台) has long wielded influence through the power of words. Her articles once served as a moral compass for a society in transition. However, as her April 1 guest article in the New York Times, “The Clock Is Ticking for Taiwan,” makes all too clear, even celebrated prose can mislead when romanticism clouds political judgement. Lung crafts a narrative that is less an analysis of Taiwan’s geopolitical reality than an exercise in wistful nostalgia. As political scientists and international relations academics, we believe it is crucial to correct the misconceptions embedded in her article,

Sung Chien-liang (宋建樑), the leader of the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) efforts to recall Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) Legislator Lee Kun-cheng (李坤城), caused a national outrage and drew diplomatic condemnation on Tuesday after he arrived at the New Taipei City District Prosecutors’ Office dressed in a Nazi uniform. Sung performed a Nazi salute and carried a copy of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf as he arrived to be questioned over allegations of signature forgery in the recall petition. The KMT’s response to the incident has shown a striking lack of contrition and decency. Rather than apologizing and distancing itself from Sung’s actions,

US President Trump weighed into the state of America’s semiconductor manufacturing when he declared, “They [Taiwan] stole it from us. They took it from us, and I don’t blame them. I give them credit.” At a prior White House event President Trump hosted TSMC chairman C.C. Wei (魏哲家), head of the world’s largest and most advanced chip manufacturer, to announce a commitment to invest US$100 billion in America. The president then shifted his previously critical rhetoric on Taiwan and put off tariffs on its chips. Now we learn that the Trump Administration is conducting a “trade investigation” on semiconductors which