Approaching the 10th anniversary of the Asian financial crisis, we must brace for a round of self-congratulatory backslapping.

In the months ahead, expect policy makers in the region to wax eloquent about how much more resilient their economies and capital markets have become since those dark days of 1997.

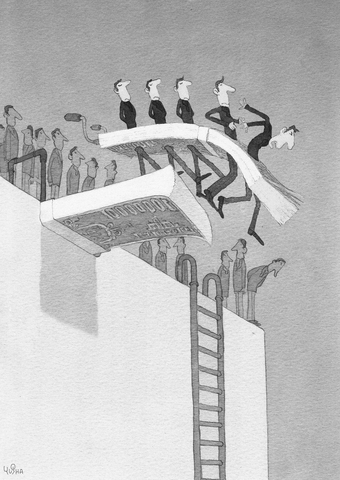

Is Asia really less vulnerable now? We won't know the answer to that question until the money that's betting on Asia's strength has undergone famed investor Warren Buffett's "naked swimmer" test.

The outward signs do support an optimistic appraisal.

The US$1.6 trillion buildup in foreign-exchange reserves in Asia, excluding Japan, in the past decade makes the fortress appear better protected against speculators than in the past.

Yet, it's reasonable to ask if reserve acquisition beyond a point is good use of local taxpayers' money, and whether it can ever be a substitute for prudent economic policies, a strong banking system and the rule of law. It's equally important to query if Asia looks stronger than it is because of a protracted slump in investments.

Asian emerging markets -- with the exception of China -- aren't saving much less than the 30 percent of GDP they were putting away before 1997.

Yet investment rates, which used to be as high as 35 percent of GDP, are about 10 percentage points lower now.

The excess of savings over investments is the current-account surplus, which is responsible for the bulk of the increase in Asian reserves.

Swimming naked

It's fine if lower investment rates reflect a new-found aversion for dubious projects funded by short-term overseas borrowings. Corporate-governance standards have improved in most parts of Asia, as has the quality of bank supervision.

Correspondingly, however, Asia's openness to global trade and capital flows has intensified. Economies and markets in the region are more closely integrated with the world -- and with each other -- than ever. Shocks emanating in one country can hit another faster and with greater ferocity than in 1997.

"It's only when the tide goes out that you learn who has been swimming naked," Buffett said in his annual chairman's letter to shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway in March 1993.

The much-quoted -- and misquoted -- comment was about inadequate preparedness in the US insurance industry to deal with catastrophes. Those words are also of immense value in making sense of the exuberance in everything from Chinese and Indian equities to Indonesian corporate bonds and Singapore property.

No Dearth of Money

Investors recently offered more than 450 billion yuan (US$58 billion) for the shares of a rail operator in Guangdong Province, China. Guangshen Railway needed only 10 billion yuan.

Six real-estate companies have tapped London's Alternative Investment Market this year to raise money to invest in India. Their pickings? More than ?1.2 billion (US$2.4 billion).

According to Singapore's Today newspaper, an investor who paid about S$14 million (US$9.1 million) last week for an apartment near Singapore's main business district turned down an offer to sell it at a 19 percent profit, or an annualized 1,000 percent profit. He wants more, the paper said.

Structural weaknesses are being brushed aside.

Global investors who snapped up US$2.7 billion in international corporate-bond issuances by Indonesian companies this year aren't at all perturbed about the dubious legality, under Indonesian jurisprudence, of offshore special-purpose vehicles that are routinely used in structuring such deals.

Ten years after the Asian crisis exposed weaknesses in governance, both graft and nepotism remain big headaches. President Chen Shui-bian's (

In Thailand, businesses linked to deposed prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra are being probed by the military junta that overthrew him in September, alleging corruption and cronyism.

Weak Institutions

The legal system in Indonesia is at best a work in progress: The building that will house the all-powerful Constitutional Court, set up in 2003, is still being built.

Malaysia looks both unable and unwilling to stop clinging to an anachronistic racial policy that does nothing to add much-needed dynamism to its economy.

As long as the tide of liquidity runs high and is left undisturbed, investors don't care about anything else.

A nationalistic whiplash against foreign buyout firms in South Korea is being shrugged off as par for the course.

Meanwhile, the Bank of Thailand this week tried to tax the deluge of funds entering the economy and got punished. Stocks collapsed. The move had to be hastily scaled down.

Will sobriety return next year? Will there be a decline in the amount of cash chasing Asian assets? Perhaps not. That's because the investment slump seen in Asian nations since the crisis may actually be part of a more widespread phenomenon.

Shortage of Assets

Behind the surfeit of worldwide liquidity, there's a global shortage of new fixed assets, noted Raghuram Rajan, the outgoing chief economist at the IMF, in a speech earlier this month.

"The glut has spilt over into markets for existing real and financial assets -- real estate, high-risk credit, private equity, art, commodities -- pushing prices higher," he said.

Except for Asian central banks suddenly draining excessive liquidity, skinny-dipping will continue to be all thrills and no embarrassment.

Andy Mukherjee is a Bloomberg News columnist. The opinions expressed are his own.

Wherever one looks, the United States is ceding ground to China. From foreign aid to foreign trade, and from reorganizations to organizational guidance, the Trump administration has embarked on a stunning effort to hobble itself in grappling with what his own secretary of state calls “the most potent and dangerous near-peer adversary this nation has ever confronted.” The problems start at the Department of State. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has asserted that “it’s not normal for the world to simply have a unipolar power” and that the world has returned to multipolarity, with “multi-great powers in different parts of the

President William Lai (賴清德) recently attended an event in Taipei marking the end of World War II in Europe, emphasizing in his speech: “Using force to invade another country is an unjust act and will ultimately fail.” In just a few words, he captured the core values of the postwar international order and reminded us again: History is not just for reflection, but serves as a warning for the present. From a broad historical perspective, his statement carries weight. For centuries, international relations operated under the law of the jungle — where the strong dominated and the weak were constrained. That

The Executive Yuan recently revised a page of its Web site on ethnic groups in Taiwan, replacing the term “Han” (漢族) with “the rest of the population.” The page, which was updated on March 24, describes the composition of Taiwan’s registered households as indigenous (2.5 percent), foreign origin (1.2 percent) and the rest of the population (96.2 percent). The change was picked up by a social media user and amplified by local media, sparking heated discussion over the weekend. The pan-blue and pro-China camp called it a politically motivated desinicization attempt to obscure the Han Chinese ethnicity of most Taiwanese.

The Legislative Yuan passed an amendment on Friday last week to add four national holidays and make Workers’ Day a national holiday for all sectors — a move referred to as “four plus one.” The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), who used their combined legislative majority to push the bill through its third reading, claim the holidays were chosen based on their inherent significance and social relevance. However, in passing the amendment, they have stuck to the traditional mindset of taking a holiday just for the sake of it, failing to make good use of