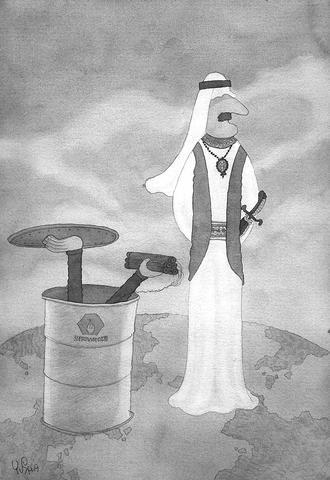

When Fadel Gheit first warned of his "nightmare scenario" that Saudi Arabia's main oil export terminal at Ras Tanura could be wiped out by terrorists, he was dismissed as an alarmist.

It was the week after the Sept. 11 attacks in New York, where he is based. But the oil analyst began to think there was another target that would have an even more devastating impact if hit.

YUSHA

As fears of upheaval in Saudi Arabia helped set world crude oil prices to 21-year highs of US$42.45 per barrel ahead of an OPEC ministerial meeting last week, there were fewer willing to scoff at Gheit.

"I cannot think of any more logical target for terrorists. It [Ras Tanura] is the nerve center for the Saudi oil trade, but also for global exports. If you can blow up the Pentagon in broad daylight, then it cannot be impossible to fly a plane into Ras Tanura -- and then you are talking US$100 [per barrel] oil," he says.

Saudi Arabia is the linchpin for world crude supplies, a key to setting prices and yet sitting on a political tinderbox due to internal dissent and having trouble securing itself against terrorism.

The repressive desert kingdom is the birthplace of Osama bin Laden, provided 15 out of the 19 attackers on 9/11 and its future problems could ultimately make petrol too expensive for us to take our cars out of the garage.

Not only is Ras Tanura or the refining center of Abqaiq dangerously exposed to being knocked out of action by militants, but Gheit also believes regime change in Saudi Arabia to a more hostile Islamic government is as inevitable as it was in Iran a quarter of a century ago. "Its only a matter of time," he claims.

But this is no headline-grabbing polemicist. The Egyptian-born American is employed by investment house Oppenheimer & Co to provide sober assessments of future oil supply and demand to investors sitting on billions of dollars worth of Wall Street financial funds.

Nor is he an armchair theorist. The 58-year-old worked in Saudi Arabia as a chemical engineer for Mobil [now ExxonMobil] while it was building facilities at Yanbu in the 1980s.

Yanbu, on the Red Sea, was attacked barely a month ago and six Western expatriate oil workers were killed; in a further attack in Khobar last weekend 22 civilians were killed. Last week shots were fired at US military personnel outside the capital Riyadh, adding to the tension and forcing a Saudi foreign affairs spokesman, Adel Al-Jubeir, to admit the oil industry was being targeted.

An assault on Ras Tanura, however, would be vastly more serious. As much as 80 percent of the near 9 million barrels of oil a day pumped out by Saudi Arabia is believed to end up being piped from fields such as Ghawar to Ras Tanura in the Gulf to be loaded on to supertankers bound for the US and the west.

Ras Tanura and other terminals are heavily patrolled and protected, the energy ministry is ringed by concrete and the streets outside patrolled by tanks and armored vehicles. But that seems to have done little to reduce a growing number of attacks on key installations.

Saudi Arabia is vital because it sits on the world's largest oil reserves, exports much more than anyone else and even more importantly has consistently acted as "swing producer" inside OPEC to try to iron out supply-and-demand blips.

The Saudi royal family -- traditionally supportive allies of the US and the UK -- promised ahead of the Western assault on Saddam Hussein that it would pump out more crude to make up any temporary shortfall should Iraqi oilfields be knocked out of action.

Similarly, Saudi Arabia promised to increase its output unilaterally when its plan for OPEC to increase production was turned down by some other OPEC ministers ahead of the meeting in Beirut last Thursday.

But this role of being friends to the west causes tension inside the country with religious and other conservatives opposed to social liberalism and Western culture.

Against this is a growing number of young, highly educated Saudis who want to throw off what they see as the semi-feudal rule by the House of Saud and adopt democracy and a new openness.

So what would happen if either Ras Tanura was put out of action or the country was taken over by an anti-Western fundamentalist movement which decided to turn off oil to the west?

Julian Lee, senior energy analyst at the Center for Global Energy Studies think tank in London, does not dismiss out of hand the US$100 per barrel oil scenario.

"I think it would be difficult to put an upper limit on the kind of panic reaction you would see in the global oil markets following the loss of Saudi supplies," he explains.

And US$80 plus could be a more likely guess according to Lee, but he also believes it would be a relatively short-lived spike because the west would take special reserves out of storage to try to stabilize the market.

The US has close to 700 million barrels of oil in its strategic petroleum reserves while many European countries, plus Japan and South Korea, have similar stocks.

The UK is still a net exporter, so in theory is self-sufficient but even if the direct impact of a loss of Saudi oil was not felt directly for say half a year, the shock would produce serious disruption and probable economic recession.

And if an extreme Saudi regime produced oil but refused to sell it to the west? Lee suggests an invasion by the US could not be ruled out but seems pretty unlikely given the difficulties in Iraq.

Saudi exports would be sucked up by China, Asia and others but in turn a lack of demand for non-Saudi supplies from those nations could then be passed on to the west, he argues. But that is not to say there would not be a problem even if Russia, Angola and the Caspian nations are all busy providing new sources of crude.

"There is no one who could step in and take over from Saud after six months, one year or even two," says the analyst from the Center for Global Energy Studies.

"But the world has lived with being dependent on politically shaky countries: look at the coup after coup in Nigeria, strike after strike in Venezuela," he argues.

Not everyone is willing to even consider the "nightmare scenario." Gerald Butt, an editor with the Middle East Economic Survey (MEES) newsletter, is dismissive of suggestions that the country is in a politically fragile state.

"The royal family is very large and very influential. It will stand together to face a common threat and sees al-Qaeda as a security issue and not a political one," he says.

As for the threat to oil installations, Butt believes they are well guarded, pushing terrorists to attack softer targets such as compounds of Western workers.

"Even with all the anarchy in Iraq, that country is still able to pump out huge quantities. It's pretty difficult to stop oil in very large countries with a huge number of oil installations," he says.

Back over the Atlantic, Gheit remains convinced that there is a real and continuing threat which would cripple the global economy.

He was in the past accused of being irresponsible by critics who said doom mongers had been predicting regime change in Saudi Arabia for 20 years, but the current situation frightens economists and consumers alike. However, there is one group that is happier than others.

Oil giants such as BP in the UK and ExxonMobil in the US have been making corporate history by notching up the largest profits ever.

As Gheit puts it: "Oil executives must be pinching themselves every morning when they wake up. They are not making money, they are printing it."

They did it again. For the whole world to see: an image of a Taiwan flag crushed by an industrial press, and the horrifying warning that “it’s closer than you think.” All with the seal of authenticity that only a reputable international media outlet can give. The Economist turned what looks like a pastiche of a poster for a grim horror movie into a truth everyone can digest, accept, and use to support exactly the opinion China wants you to have: It is over and done, Taiwan is doomed. Four years after inaccurately naming Taiwan the most dangerous place on

Wherever one looks, the United States is ceding ground to China. From foreign aid to foreign trade, and from reorganizations to organizational guidance, the Trump administration has embarked on a stunning effort to hobble itself in grappling with what his own secretary of state calls “the most potent and dangerous near-peer adversary this nation has ever confronted.” The problems start at the Department of State. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has asserted that “it’s not normal for the world to simply have a unipolar power” and that the world has returned to multipolarity, with “multi-great powers in different parts of the

President William Lai (賴清德) recently attended an event in Taipei marking the end of World War II in Europe, emphasizing in his speech: “Using force to invade another country is an unjust act and will ultimately fail.” In just a few words, he captured the core values of the postwar international order and reminded us again: History is not just for reflection, but serves as a warning for the present. From a broad historical perspective, his statement carries weight. For centuries, international relations operated under the law of the jungle — where the strong dominated and the weak were constrained. That

The Executive Yuan recently revised a page of its Web site on ethnic groups in Taiwan, replacing the term “Han” (漢族) with “the rest of the population.” The page, which was updated on March 24, describes the composition of Taiwan’s registered households as indigenous (2.5 percent), foreign origin (1.2 percent) and the rest of the population (96.2 percent). The change was picked up by a social media user and amplified by local media, sparking heated discussion over the weekend. The pan-blue and pro-China camp called it a politically motivated desinicization attempt to obscure the Han Chinese ethnicity of most Taiwanese.