Watch yourself carefully, and think how you could be seen in the eyes of others." This is the lesson I was taught in elementary school in Tokyo.Nowadays, however, that piece of wisdom seems less widely shared in Japan.Regrettably, the same seems to be true in neighboring countries, where Japanese attitudes are criticized stridently.

A harsh debate concerning a new history textbook for junior high schools in Japan has prompted me to think about how the tone of a debate shapes perceptions. 19 years ago, I lived in Seoul as a language student when the first angry protests against Japanese textbooks occurred. It took years to recover from this, but since then Korean-Japan relations have improved significantly, despite the fact that some politicians sometimes talk about Japan's past in a thoughtless way. As the result of numerous primeministerial apologies for Japan's former colonization and aggression in Asia, expanded economic and grassroots exchanges are today a normal part of relations between Japan and its neighbors.

Indeed, during his visit to Japan in 1998, President Kim Dae-jung openly boosted reconciliation between our two countries. The upcoming World Cup Soccer Tournament in 2002, which Japan and South Korea will jointly host, should have been the crowning symbol of these friendly relations, in sharp contrast to a century ago, when Japanese imperialism was on the march. Instead, the dispute over a new Japanese history textbook has claimed centerstage. Even though it passed official examinations by Japan's government, which insisted on numerous revisions, the textbook in question does clearly intend to glorify Japan's history. So it is not unreasonable for Koreans and Chinese to object to its use, particularly as they see it as aimed at justifying Japan's wars against them.

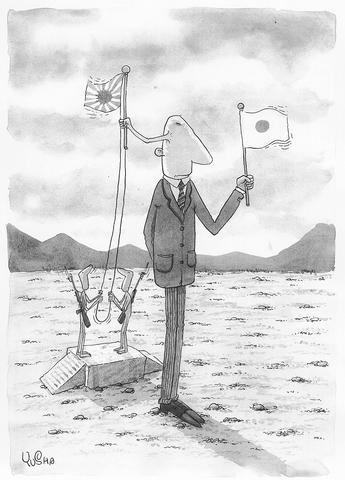

ILLUSTRAION: YU SHA

While I disagree with the textbook's thrust, I don't want to over estimate its importance. It is only one among eight possible textbooks for junior high schools. More importantly, no public school district adopted the textbook for use by its students, mostly because local education committees rejected its message. That result should demonstrate to everyone that an unhealthy nationalism is not supported by a majority in Japan.

So, while I sympathize with our neighbors and their concerns, I am uneasy about foreign governments demanding -- directly -- that Japan modify specific details in its textbooks. It is Japan's responsibility to control the content of school textbooks. Japan must be more scrupulous in writing textbooks, of course, but what country anywhere would easily bow to outside pressure where the education of its children is concerned? It is puzzling that numerous planned exchanges between Japanese and Korean grassroots organizations were canceled by the Korean side because of this dispute. Perhaps these cancellations were seen as a type of sanction on Japan, but such attitudes tend to be seen as "overly emotional" in Japanese eyes, and may provoke a resurgence among some Japanese of the very nationalism the Koreans loathe.

If the Korean people had, instead, chosen to continue the exchanges and mentioned their objections to the textbooks in friendly and frank discussions, Japan's people would have understood and respected the Koreans more. I hope the Koreans will come to believe in our good faith a little more when they see how few school districts adopt the textbook to which they object. That good faith was tested again in the eyes of Koreans and Chinese by the visit of Prime Minister Junichero Koizumi to the Yasukuni Shrine. Koizumi argues that the purpose of his visit was merely to mourn for the Japanese soldiers who died during WWII.

But visits to Yasukuni, like history textbooks, have a complex history, dating back to 1985 when then prime minister Nakasone made an "official visit" to Yasukuni, ignoring strident domestic opposition. He was forced not to repeat the visit because of severe Chinese protests. It is true that "Class A" war criminals from WWII are enshrined in Yasukuni alongside other rank and file soldiers, and Yasukuni is indeed seen as a symbol of Japan's past militarism by Asian countries. So Koizumi can hardly expect silent understanding about his visit.

Yet the manner in which Japan's neighbors objected stunned many Japanese. China's foreign minister even went so far as to say, on camera to Japanese reporters after his meeting with Japan's foreign minister: "I told her to stop the visiting." In Japanese, this phrase carries a very strong connotation of command, a posture that may further stoke Japanese xenophobia.

Perhaps Koizumi intended, by his visit, to call attention to a perceived Chinese insensitivity to Japanese concerns. China's rapid military buildup of recent years and its obsessions with nuclear missile development are not easily understood by a Japanese public who see their country as contributing mightily in terms of economic assistance to China.

But manipulating symbols to send diplomatic messages rarely works effectively, for symbols are imprecise and their meanings are easily distorted.

Koizumi's visit may, indeed, only further stimulate China's military buildup. In this, sadly, we can begin to glimpse a return to the sad downward spiral among neighbors that once gripped this region. His visit to Yasukuni over, Koizumi must do all that he can to prevent that unfortunate spiral from repeating itself.

Yoshibumi Wakamiya is a guest scholar of The Brookings Institution. He is senior political writer at Asahi Shimbun and the author of The Postwar Conservative View Of Asia.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

They did it again. For the whole world to see: an image of a Taiwan flag crushed by an industrial press, and the horrifying warning that “it’s closer than you think.” All with the seal of authenticity that only a reputable international media outlet can give. The Economist turned what looks like a pastiche of a poster for a grim horror movie into a truth everyone can digest, accept, and use to support exactly the opinion China wants you to have: It is over and done, Taiwan is doomed. Four years after inaccurately naming Taiwan the most dangerous place on

Wherever one looks, the United States is ceding ground to China. From foreign aid to foreign trade, and from reorganizations to organizational guidance, the Trump administration has embarked on a stunning effort to hobble itself in grappling with what his own secretary of state calls “the most potent and dangerous near-peer adversary this nation has ever confronted.” The problems start at the Department of State. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has asserted that “it’s not normal for the world to simply have a unipolar power” and that the world has returned to multipolarity, with “multi-great powers in different parts of the

President William Lai (賴清德) recently attended an event in Taipei marking the end of World War II in Europe, emphasizing in his speech: “Using force to invade another country is an unjust act and will ultimately fail.” In just a few words, he captured the core values of the postwar international order and reminded us again: History is not just for reflection, but serves as a warning for the present. From a broad historical perspective, his statement carries weight. For centuries, international relations operated under the law of the jungle — where the strong dominated and the weak were constrained. That

The Executive Yuan recently revised a page of its Web site on ethnic groups in Taiwan, replacing the term “Han” (漢族) with “the rest of the population.” The page, which was updated on March 24, describes the composition of Taiwan’s registered households as indigenous (2.5 percent), foreign origin (1.2 percent) and the rest of the population (96.2 percent). The change was picked up by a social media user and amplified by local media, sparking heated discussion over the weekend. The pan-blue and pro-China camp called it a politically motivated desinicization attempt to obscure the Han Chinese ethnicity of most Taiwanese.