John Browett, the chief executive of Tesco.com, the online arm of Britain's largest supermarket chain, is no stranger to the intricacies of home delivery. So when he visited the warehouse of an Internet grocery company in the US last year, he noticed that it was using a fancy conveyor belt to ferry boxes around a corner, when a similar gadget would have done the job for half the price.

Company executives defended their choice, Browett recalled in a recent interview, as worth the expense because it enabled them to start up sooner.

"People were making some very strange decisions," he said. "They were saying things like, `I'm going to get the revenue first and work out the cost structure later."'

PHOTO: NY TIMES

Tesco was not in such a hurry, but what was the rush? Instead of trying to revolutionize the mundane chore of grocery shopping with a high-tech approach relying on expensive centralized warehouses, Tesco simply added a modest online delivery service to its traditional supermarket operation.

And now that Webvan, the most prominent of the various stand-alone Internet food shopping companies has gone bust after pouring US$1.2 billion into the attempt, Tesco's tortoise-like approach to the business is clearly more likely to succeed where the rabbits that raced ahead have failed.

Tesco neither designed a glitzy Web site nor spent millions on state-of-the-art distribution facilities. It has invested just US$56 million in its online grocery endeavor, a business that now has US$422 million in annual sales, making it the largest in the world. Last year, Tesco earned a pre-tax profit of US$1.6 billion on total sales of US$30 billion.

Moreover, Tesco says it makes an undisclosed annual profit on its online service, which analysts estimate to be in the range of US$7 million. And the company is exporting its know-how to the US in a deal with GroceryWorks, an Internet venture now half-owned by Safeway.

Still, while Tesco's store-oriented approach appears to be winning out, the debate over which method works best is not quite over. Publix Super Markets of Lakeland, Florida, by contrast, is building big fulfillment centers for its online operations. Still others, like Ahold, a Dutch company that recently bought the rest of Peapod, a grocery shopping startup serving Chicago and some cities in the Northeast, is experimenting with a hybrid bricks-and-clicks method.

Jan Hol, an Ahold spokesman, said Peapod is making a profit in the Chicago market, although he declined to provide details. In all, Ahold's online sales are expected to total US$220 million this year out of sales of US$52 billion.

With such deep-pocketed supermarket chains taking the place of idealistic but cash-strapped entrepreneurs, this will be a battle drawn out over decades rather than years. Even the most optimistic forecasts now expect food deliveries by online ordering to remain a relatively small share of the overall grocery business for the foreseeable future. Jupiter Media Metrix predicts that by 2006, online food shopping in the US will reach US$11.3 billion business, or 2 percent of all grocery sales, up from US$800 million, or 0.2 percent of total sales this year.

"The question is not, `What will this business be like in 10 years," Browett said, "but what will it be like in 30 years?"'

For the better part of the last decade, Tesco has been concerned with improving operations at its stores rather than experimenting in cyberspace. That penchant for efficiency paid off by helping Tesco increase its share of the retail food market in Britain from 10 percent in 1991 to 16 percent today, putting it ahead of Sainsbury as the country's leading supermarket chain.

Tesco took its first online order in 1996, inspired by futuristic technologies that Terry Leahy, its chief executive, had seen demonstrated at an Andersen Consulting Smart Store a year earlier. But Tesco was still unsure whether to pursue the warehouse model or to have its 690 British stores double as distribution centers.

Both strategies had risks. Building huge warehouses would cost millions of pounds that Tesco was hesitant to spend on an unproven service. But packing and picking groceries from stores could clog the aisles and frustrate customers.

And so Tesco ran a series of calculations that turned up surprising results.

To get enough volume to justify the cost of building a warehouse, Tesco determined it would have to serve too wide a swath of the population from one location. In London, for instance, a single warehouse would have had to deliver to an area that would have taken hours to cover even if London's traffic was not as notoriously jammed as it is.

But by delivering from local stores, Tesco found, no route would take more than 25 minutes.

Once it settled on its approach, Tesco set about creating a system that would allow it to pick and pack groceries efficiently from stores. Rather than walking up and down the aisles pulling product from the shelves individually, employees use carts equipped with a computer that determines the most effective path, allowing six orders to be filled simultaneously. The products are automatically scanned into a virtual cash register, all of which has helped to reduce picking time by one-third, Browett said.

Last, Tesco determined there was no way to make a profit unless it charged a delivery fee per order of 5 pounds, or about US$7. Many competitors in the US shied away from imposing such a hefty upfront fee for fear of turning off potential customers.

Shoppers like Susan Goulding, a 34-year-old resident of Middlesex, England, are willing to pay.

"It's much more convenient to order the stuff over the site and have them deliver it rather than spending a few hours in the supermarket," Gould said, adding that since she gave birth to a son 10 months ago she does her grocery shopping online every week.

Even though the evidence showed Tesco was heading in the right direction, by 1999 executives were second-guessing their assumptions, given the conventional wisdom in the US, where Webvan executives were publicly decrying a store delivery strategy. Tesco hired outside consultants to double-check its math, but they came up with the same conclusions.

Many of those findings are now supported by the Internet upstarts that had dismissed Tesco's approach earlier.

GroceryWorks, of Carrollton, Texas, began delivering from a warehouse in December 1999. Two months later, the executives realized the business model had severe flaws.

"We knew right away that we had to get the product costs down," said Jeffrey Cushman, the company's chief financial officer. But without the buying power of the larger grocery chains it could not arrange competitive deals from suppliers.

The other problem was with its warehouse system. "A fulfillment center is so big that you never get the density until you run out of money," Cushman said.

And so Cushman began canvassing traditional retailers in search of a partner. Over the past 14 months, Safeway has invested US$40 million for a 50 percent stake. And in June, Tesco kicked in US$22 million for a 35 percent stake.

With the blessing of its new investors, GroceryWorks is closing its three distribution centers, built at a cost of roughly US$7 million each, and is temporarily ceasing operations. When it reopens, it will operate under the Safeway name, using the Tesco model of store picking and packing.

But just because Tesco has managed to work out the initial challenges does not mean the company will necessarily dominate the future business.

Some analysts and investors also question whether Tesco's online grocery operation would be profitable if it were truly evaluated as a separate business.

Since Tesco uses its existing stores to fulfill online orders, Matthews asks, shouldn't it allocate some depreciation of those assets to its online venture? But given that the online operations are consolidated within the company's overall financial statements, he said, investors have no way of knowing whether the company is accounting for these costs properly.

Browett said Tesco allocates some store depreciation costs as well as all other relevant expenses to its online operation, but declined to provide financial details.

Then there are questions as to how easily Tesco's methods will translate to the US.

"The UK is God's perfect food laboratory," said Andrew Fowler, an analyst with Merrill Lynch in London. "It is a densely populated, homogenous island."

By contrast, the US is ethnically diverse, with a far-flung population. Tesco is able to deliver to 90 percent of the British population from its existing stores; in the US, no grocery chain commands national status.

Moreover, Tesco had the luxury of developing its system cloistered in England, where competition from online start-ups and more traditional players has been negligible. But now Sainsbury and other British supermarkets are pursuing their own strategies.

Tesco is convinced that its lead will hold up and that its decentralized approach will work for many years.

"We can do 10 times the sales we're doing today out of these stores," Browett said.

It all might have turned out differently for Tesco, Browett conceded, if the company had been based in the US, where it was easier to be caught up in revolutionary visions for the Internet.

"We were lucky," he said, "that we weren't in the middle of the maelstrom."

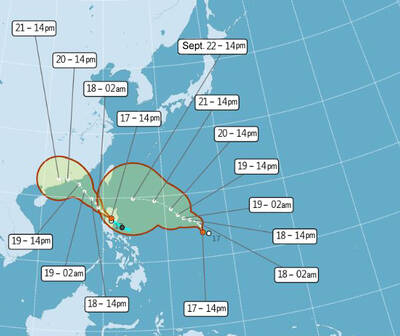

One of two tropical depressions that formed off Taiwan yesterday morning could turn into a moderate typhoon by the weekend, the Central Weather Administration (CWA) said yesterday. Tropical Depression No. 21 formed at 8am about 1,850km off the southeast coast, CWA forecaster Lee Meng-hsuan (李孟軒) said. The weather system is expected to move northwest as it builds momentum, possibly intensifying this weekend into a typhoon, which would be called Mitag, Lee said. The radius of the storm is expected to reach almost 200km, she said. It is forecast to approach the southeast of Taiwan on Monday next week and pass through the Bashi Channel

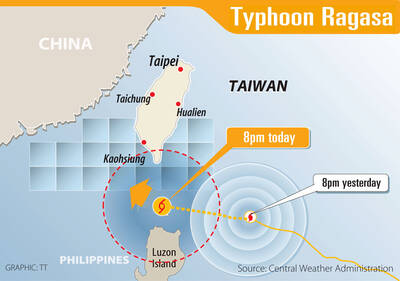

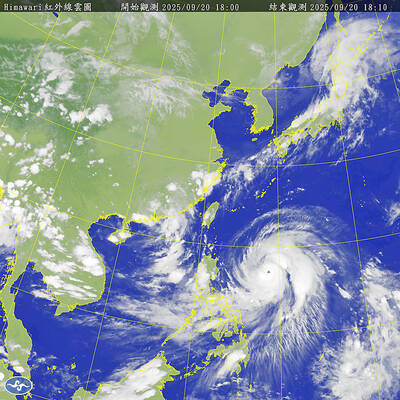

WARNING: People in coastal areas need to beware of heavy swells and strong winds, and those in mountainous areas should brace for heavy rain, the CWA said The Central Weather Administration (CWA) yesterday issued sea and land warnings for Typhoon Ragasa, forecasting that it would continue to intensify and affect the nation the most today and tomorrow. People in Hualien and Taitung counties, and mountainous areas in Yilan and Pingtung counties, should brace for damage caused by extremely heavy rain brought by the typhoon’s outer rim, as it was upgraded to a super typhoon yesterday morning, the CWA said. As of 5:30pm yesterday, the storm’s center was about 630km southeast of Oluanpi (鵝鑾鼻), Taiwan’s southernmost tip, moving northwest at 21kph, and its maximum wind speed had reached

The Central Weather Administration (CWA) yesterday said that it expected to issue a sea warning for Typhoon Ragasa this morning and a land warning at night as it approached Taiwan. Ragasa intensified from a tropical storm into a typhoon at 8am yesterday, the CWA said, adding that at 2pm, it was about 1,110km east-southeast of Oluanpi (鵝鑾鼻), Taiwan’s southernmost tip. The typhoon was moving northwest at 13kph, with sustained winds of up to 119kph and gusts reaching 155kph, the CWA Web site showed. Forecaster Liu Pei-teng (劉沛滕) said that Ragasa was projected to strengthen as it neared the Bashi Channel, with its 200km

PUBLIC ANNOUNCEMENTS: Hualien and Taitung counties declared today a typhoon day, while schools and offices in parts of Kaohsiung and Pingtung counties are also to close Typhoon Ragasa was forecast to hit its peak strength and come closest to Taiwan from yesterday afternoon through today, the Central Weather Administration (CWA) said. Taiwan proper could be out of the typhoon’s radius by midday and the sea warning might be lifted tonight, it added. CWA senior weather specialist Wu Wan-hua (伍婉華) said that Ragasa’s radius had reached the Hengchun Peninsula by 11am yesterday and was expected to hit Taitung County and Kaohsiung by yesterday evening. Ragasa was forecast to move to Taiwan’s southern offshore areas last night and to its southwestern offshore areas early today, she added. As of 8pm last night,