These days whenever Chanette Thompson stubs her toe or knocks her funny bone, she is likely to shout out “Aish,” the Korean equivalent of “Oh no” or “Darn it.”

Thompson, a make-up artist who lives in Los Angeles, has never been to South Korea, and is not even close to being fluent in Korean. That she is prone to curse in a language she does not speak is a testament to one thing — her insatiable consumption of South Korean TV.

Thompson first happened upon South Korean shows more than a decade ago while flipping through the outer reaches of free broadcast TV channels in Los Angeles. Before long, she was enthralled with Pink Lipstick, a South Korean romantic comedy with a handsome protagonist and a melodramatic storyline, which reminded her of The Young and the Restless, a soap opera she used to watch with her grandmother. From there, her fascination took off.

Photo: Reuters

Today her Netflix queue is filled with South Korean dramas. She subscribes to another streaming service, Viki, to get access to even more of the shows, she goes to South Korean restaurants to try out the food she has seen on screen and is planning a trip to South Korea in 2025.

“I watch American TV, but I watch way more Korean TV,” she said.

Thompson is in good company. South Korean TV has blossomed into one of the most popular types of programming on the planet. The success of the Netflix Inc series Squid Game, following on the heels of the hit film Parasite, has helped turn Seoul into one of the entertainment capitals of the world.

South Korea is the single largest producer of successful shows in Asia, research firm Media Partners Asia said.

It is also the largest producer of hit series globally for Netflix outside the US, and more than 60 percent of its customers watched a South Korean show last year, Media Partners Asia said.

For two consecutive weeks last month, The Glory — a 16-episode drama about a woman seeking revenge against the tormentors from her childhood — was the most-watched show on Netflix, drawing about as much viewership as the two biggest English-language series combined. It was one of Netflix’s 10 most popular series in more than 90 countries, including Argentina, France, India and South Africa.

Netflix budgeted US$500 million for South Korea in 2021 and, after the success of Squid Game and other series, increased its output to at least 34 original programs this year.

It now spends close to US$1billion a year, Media Partners Asia said.

Following Netflix’s lead, some of the world’s largest media companies are scrambling to capitalize on the surging interest from viewers such as Thompson. Disney+ and Apple TV+ are among the global streaming services exploring deals that would step up their investment in the country. Amazon.com Inc, which does not operate a streaming service in South Korea, is also buying Korean shows because of their popularity elsewhere in the world.

Yet the success of South Korean TV did not happen overnight.

In the 1950s, Lee Byung-chul, the founder of the electronics-to-shipbuilding giant Samsung Group, created CJ CheilJedang, a food and health conglomerate. Producing TV was not part of the original plan, but during the twilight of the Cold War, as the cultural and economic might of the US helped to topple the Soviet Union, the political leaders of South Korea began encouraging its largest companies to invest in entertainment. The soft power, they believed, might prove nationally advantageous.

In the 1990s, two of Lee’s grandchildren, Lee Jay-hyun and Miky Lee, dove in headlong, transforming CJ into a sprawling entertainment conglomerate. They created and acquired a handful of domestic TV networks, live-event businesses and record labels.

In 1994, they invested US$300 million in DreamWorks SKG, a new movie studio being formed by Steven Spielberg, Jeffrey Katzenberg and David Geffen. In 1998, the CJ Group opened the country’s first multiplex, spawning a successful cinema chain that would go on to manage theaters throughout Asia.

The Lees were initially more focused on making films rather than television. For years, the South Korean TV industry had been ruled by a handful of local networks that churned out popular, formulaic romance dramas, while the more prestigious storytelling often landed in movie theaters.

In 2010, the Lees created a new division to produce dramas for South Korean TV networks, and over time, the company went on to strike deals with many of the nation’s best writers and directors.

In 2016, the Lees spun out Studio Dragon from CJ ENM, their entertainment company. That same year, Studio Dragon produced Guardian: The Lonely and Great God. The series about a military general from the 10th century who is cursed with immortality became the first cable drama in South Korean history to reach 20 percent of TV viewers with a single episode.

A few years earlier, when Netflix was first expanding into Asia, the company initially focused on making inroads in Japan, which Western executives often think of as the cultural capital of the region thanks to the global appeal of Japanese anime and the achievements of auteurs such as Akira Kurosawa and Hayao Miyazaki.

However, as they cultivated deeper relationships in the region, Netflix executives started to realize that it was South Korea, not Japan, that would be the key to attracting legions of new subscribers throughout Asia.

TV networks in Taiwan, Japan and Hong Kong were already buying up popular South Korean TV series and re-airing them on broadcast and cable networks with great fanfare. So far, nobody outside of the region had scooped up many of the streaming rights.

In the early days of streaming, fans of South Korean dramas often illegally downloaded episodes, or they turned to Drama Fever, a once promising US start-up service owned by Warner Bros, that was losing steam amid AT&T Inc’s tangled 2016 takeover of its parent company.

Minyoung Kim and Don Kang, Netflix’s top executives in South Korea, saw an opening. Kang, who had worked at CJ Group, was well versed in South Korean programming.

“Interest in Korean content was very, very high in Asia, but there was no real demand from the businesses outside Asia,” Kang said.

In 2019, Netflix signed a deal, licensing the streaming rights to many Studio Dragon shows, and took a small stake in the company. Under the new arrangement, series such as Hometown Cha-Cha-Cha, a dentist-themed romantic comedy, would debut on South Korean TV and then appear hours later on Netflix.

In the years that followed, millions of customers in South Korea signed up for the streaming service, helping to turn Asia into Netflix’s fastest-growing market. By adding subtitles and dubbing to the South Korean series, Netflix was soon able to introduce the programming to legions of new viewers in Latin America, Europe and the US.

“We opened up an easy way for people outside Asia to get to know Korean content in the language they speak,” Kang said.

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic only heightened interest from audiences overseas, as people who were stuck at home and streaming large amounts of programming started sampling shows from other parts of the world.

By the fall of 2021, South Korean shows, including Squid Game, All of Us Are Dead and Extraordinary Attorney Woo, were regularly popping up on the lists of Netflix’s most popular programming. Globally, Netflix users started spending more time watching shows from South Korea than from any country outside the US, including the UK.

Global streaming services have enabled the South Korean drama to evolve from the more formulaic programs seen on broadcast networks, Studio Dragon cochief executive offcier Kim Jey-hyun said.

Story arcs now stretch over more episodes, and characters are less one-dimensional. Shows also deal with darker themes such as class, abuse and the undead, but they do so without pandering to foreign viewers. The biggest hits are still quintessentially South Korean.

Now the South Korean entertainment industry is hoping to keep the trend going. Studios have increased their output of drama series by more than 50 percent over the past three years, releasing more than 125 shows last year.

CJ ENM has a long way to go to catch Western media giants. It has an enterprise value of about US$4 billion, less than Lions Gate Entertainment Corp, the producer of the John Wick movie franchise.

However, Studio Dragon’s success is inspiring CJ ENM, its majority shareholder, to try and compete head-to-head with Western media giants on the global stage. The company has set up two new production divisions — CJ ENM Studios and Fifth Season — to increase its output. Recently, the company created a division of Studio Dragon in Japan, and is also expanding into Thailand, which has a growing community of filmmakers.

Northeast of Seoul in the town of Paju, CJ ENM has built a new TV studio, the largest in the country, housing 13 sound stages, including one that is about the size of the White House. Stage two is the home of a virtual production studio modeled after the technology used on Walt Disney Co’s The Mandalorian.

“If someone writes about the media industry, I would love for there to be three companies,” said Steve Chung, the cochief executive officer of CJ in the US and the company’s chief global officer. “Netflix is the top streamer, Disney is the family branded company and CJ as the most consequential non English-language media company in the world.”

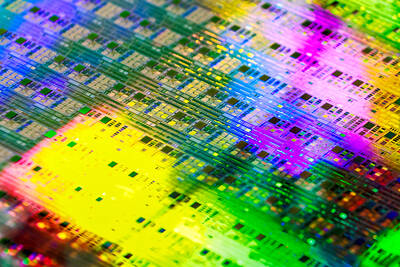

SEMICONDUCTOR SERVICES: A company executive said that Taiwanese firms must think about how to participate in global supply chains and lift their competitiveness Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) yesterday said it expects to launch its first multifunctional service center in Pingtung County in the middle of 2027, in a bid to foster a resilient high-tech facility construction ecosystem. TSMC broached the idea of creating a center two or three years ago when it started building new manufacturing capacity in the US and Japan, the company said. The center, dubbed an “ecosystem park,” would assist local manufacturing facility construction partners to upgrade their capabilities and secure more deals from other global chipmakers such as Intel Corp, Micron Technology Inc and Infineon Technologies AG, TSMC said. It

People walk past advertising for a Syensqo chip at the Semicon Taiwan exhibition in Taipei yesterday.

NO BREAKTHROUGH? More substantial ‘deliverables,’ such as tariff reductions, would likely be saved for a meeting between Trump and Xi later this year, a trade expert said China launched two probes targeting the US semiconductor sector on Saturday ahead of talks between the two nations in Spain this week on trade, national security and the ownership of social media platform TikTok. China’s Ministry of Commerce announced an anti-dumping investigation into certain analog integrated circuits (ICs) imported from the US. The investigation is to target some commodity interface ICs and gate driver ICs, which are commonly made by US companies such as Texas Instruments Inc and ON Semiconductor Corp. The ministry also announced an anti-discrimination probe into US measures against China’s chip sector. US measures such as export curbs and tariffs

The US on Friday penalized two Chinese firms that acquired US chipmaking equipment for China’s top chipmaker, Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp (SMIC, 中芯國際), including them among 32 entities that were added to the US Department of Commerce’s restricted trade list, a US government posting showed. Twenty-three of the 32 are in China. GMC Semiconductor Technology (Wuxi) Co (吉姆西半導體科技) and Jicun Semiconductor Technology (Shanghai) Co (吉存半導體科技) were placed on the list, formally known as the Entity List, for acquiring equipment for SMIC Northern Integrated Circuit Manufacturing (Beijing) Corp (中芯北方積體電路) and Semiconductor Manufacturing International (Beijing) Corp (中芯北京), the US Federal Register posting said. The