Taiwan is racing to set up specialized “chip schools” that run year-round to train its next generation of semiconductor engineers and cement its dominance of the crucial industry.

The plans, championed by President Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文), come as chip companies plow billions of dollars into capacity expansion to make the “brains” that power everything from smartphones to fighter jets, amid a global shortage. Chip giant Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) alone this year is to spend up to US$44 billion and hire more than 8,000 employees.

Jack Sun (孫元成), who retired as TSMC’s chief technology officer in 2018 and became dean of one of the new semiconductor graduate schools last year, said that chip companies need a lot more and better talent to compete on the global stage.

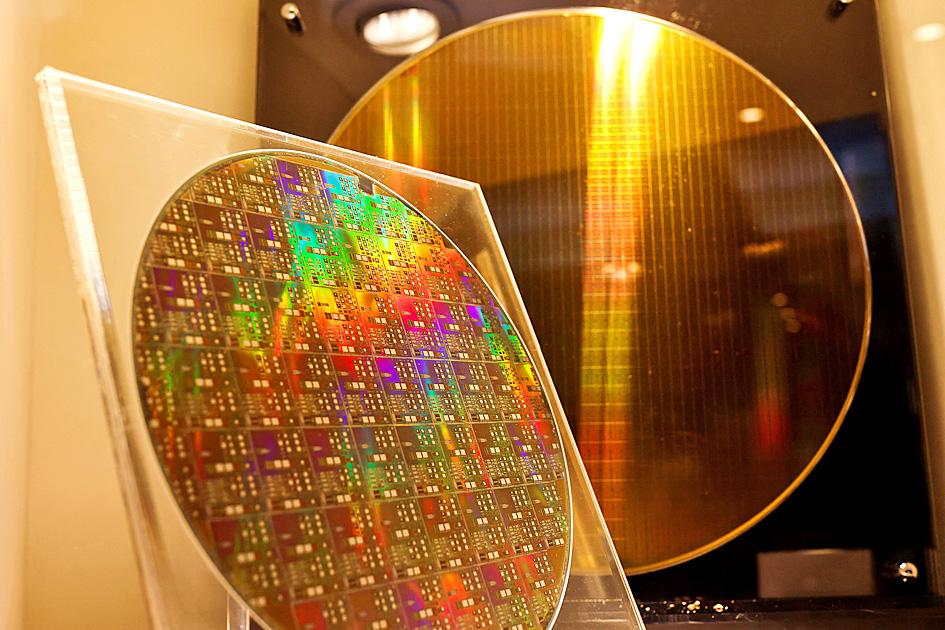

Photo: Ann Wang, Reuters

“Indeed, I’m devoting some of my golden years to talent development,” Sun said with a laugh, before pointing out that his former TSMC colleague Burn Lin (林本堅) is older and the dean of another chip school.

Sun and Lin, industry heavyweights turned educators, embody the government’s strategy of strengthening industry-academia ties to remain a critical node in the global chip supply chain.

“In the cultivation of semiconductor talent, we are racing against time,” Tsai said in December at the unveiling of National Tsing Hua University’s College of Semiconductor Research.

The government has partnered with leading chip companies to pay for the schools. The first four were established at top universities last year, each with a quota of about 100 master’s and doctorate students, and another has been approved, the Ministry of Education said.

“I specifically requested these schools stay open year-round, without winter and summer breaks, so that we can quickly produce talent,” Tsai said at another unveiling.

The chip talent shortage is a top concern for the nation, which considers the industry critical to economic growth and national security, especially as China steps up military pressure on Taiwan.

Even before the global chip shortage, companies worried that a talent crunch could hobble the booming industry, said Terry Tsao (曹世綸), president of the SEMI Taiwan industry group.

In September 2019, Tsao and about 20 Taiwanese and foreign chip executives met with Tsai and urged the government to address the issue.

“Everyone thinks this is the top priority,” Tsao said.

As countries pledge billions for domestic chip production and companies scramble to build new plants, the need for people to design, manufacture and test chips has intensified.

In the fourth quarter of last year, there were nearly 34,000 chip industry job openings per month on average on 104 Job Bank (104人力銀行), a popular recruitment platform, about 50 percent more than a year earlier, according to data provided by the job bank.

Although demand for workers has soared, Taiwan — with one of the world’s lowest birthrates — has been producing fewer engineers over the past decade. Even fewer are enrolling in the doctoral programs that best prepare engineers to develop breakthrough technologies.

Competing over a limited pool, Taiwanese companies have rolled out higher wages, longer parental leave, billboard ads and scholarships to poach engineers from other firms and recruit fresh talent from campuses.

Taiwan can no longer sustain local industry’s needs, and foreign competition would further affect its long-term research and development (R&D) talent growth, said chip designer MediaTek Inc (聯發科), which this year plans to recruit more than 2,000 R&D employees and double its number of summer interns to lock in talent earlier.

Companies are also looking abroad. United Microelectronics Corp (聯電), which plans to recruit more than 1,500 new employees in Taiwan this year, said it is expanding its overseas recruitment channels.

In May last year, the government passed a regulation to make it easier for schools and companies to collaborate in key fields of national interest, paving the way for chip schools.

The looser rules allow the schools to bring in corporate funding and increase faculty pay.

Beyond funding, companies would help design curricula, send executives to give talks, and provide chip experts to teach courses and advise research projects.

As chip technology develops rapidly, “there is a gap between what you study and what you need to use at the company,” said Su Yan-kuin (蘇炎坤), dean of the chip school at National Cheng Kung University, in his office, while workers assembled beams next door.

“We work closely with industry, connecting industry and academia, thus narrowing the gap,” Su said.

Lin Chun-yu, 24, an incoming doctorate student at Su’s school, would receive NT$40,000 per month, a stipend doctorate students in Taiwan do not typically receive.

“Close collaboration with the industry now will be very helpful for my studies and for employment,” he said.

While some are concerned that a singular focus on semiconductors will come at the cost of other industries, others say such costs are necessary.

“It will create imbalances in the ecosystem,” said Yeh Wen-kuan (葉文冠), director-general of the Taiwan Semiconductor Research Institute (台灣半導體研究中心), about the chip schools attracting students from other fields.

“But there’s no other choice right now,” he added. “Taiwan’s lifeblood, you have to first hold on to it. If you don’t hold on to it, how can you let Taiwan’s economy progress?”

Real estate agent and property developer JSL Construction & Development Co (愛山林) led the average compensation rankings among companies listed on the Taiwan Stock Exchange (TWSE) last year, while contract chipmaker Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) finished 14th. JSL Construction paid its employees total average compensation of NT$4.78 million (US$159,701), down 13.5 percent from a year earlier, but still ahead of the most profitable listed tech giants, including TSMC, TWSE data showed. Last year, the average compensation (which includes salary, overtime, bonuses and allowances) paid by TSMC rose 21.6 percent to reach about NT$3.33 million, lifting its ranking by 10 notches

Popular vape brands such as Geek Bar might get more expensive in the US — if you can find them at all. Shipments of vapes from China to the US ground to a near halt last month from a year ago, official data showed, hit by US President Donald Trump’s tariffs and a crackdown on unauthorized e-cigarettes in the world’s biggest market for smoking alternatives. That includes Geek Bar, a brand of flavored vapes that is not authorized to sell in the US, but which had been widely available due to porous import controls. One retailer, who asked not to be named, because

SEASONAL WEAKNESS: The combined revenue of the top 10 foundries fell 5.4%, but rush orders and China’s subsidies partially offset slowing demand Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) further solidified its dominance in the global wafer foundry business in the first quarter of this year, remaining far ahead of its closest rival, Samsung Electronics Co, TrendForce Corp (集邦科技) said yesterday. TSMC posted US$25.52 billion in sales in the January-to-March period, down 5 percent from the previous quarter, but its market share rose from 67.1 percent the previous quarter to 67.6 percent, TrendForce said in a report. While smartphone-related wafer shipments declined in the first quarter due to seasonal factors, solid demand for artificial intelligence (AI) and high-performance computing (HPC) devices and urgent TV-related orders

MINERAL DIPLOMACY: The Chinese commerce ministry said it approved applications for the export of rare earths in a move that could help ease US-China trade tensions Chinese Vice Premier He Lifeng (何立峰) is today to meet a US delegation for talks in the UK, Beijing announced on Saturday amid a fragile truce in the trade dispute between the two powers. He is to visit the UK from yesterday to Friday at the invitation of the British government, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs said in a statement. He and US representatives are to cochair the first meeting of the US-China economic and trade consultation mechanism, it said. US President Donald Trump on Friday announced that a new round of trade talks with China would start in London beginning today,