Squatting on spongy soil, a climate scientist laid a small cone-shaped device to “measure the breathing” of a peat bog in the northern part of Canada’s Quebec province.

Michelle Garneau, a university researcher and a member of the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), was collecting the first data on areas flooded to build the new Romaine River hydroelectric dams in a bid to assess the project’s impact on the region.

While renewable hydroelectricity itself is considered to be one of the cleanest sources of energy on the planet, there is no proven model for calculating the greenhouse gas emissions released by flooding huge areas behind new dams.

Photo: AFP

With construction of four new dams on the Romaine River in northern Quebec nearly complete, researchers saw an opportunity to try out new techniques to measure its carbon footprint.

The team led by Garneau zeroed in on a swamp a mere stone’s throw from the raging river in the wilds of Canada’s boreal forest, an area accessible only by helicopter.

After landing, she took several boxes out of the belly of the aircraft and placed them next to some solar panels and a portable weather station that she and her students installed over the summer. The devices are expected to produce sample data within two years.

“Every 20 minutes, the cone will capture and measure the breathing of the soil,” Garneau said, placing a transparent device that resembles a handbell on the lichen, as wild geese honked and cackled overhead.

She took a few steps further on the unstable ground and placed a box that connects to sensors already sunk into the ground.

“This automated device to measure the photosynthetic activity records the [carbon dioxide] and methane emissions every three minutes, for hours,” the researcher said.

Carbon dioxide and methane emissions are the main sources of global warming.

Another team is measuring carbon dioxide emissions from artificial lakes created by flooding lands behind dams for eventual comparison.

About one-third of the world’s land area is covered by forests, which act as sinks for greenhouse gases.

Canada’s enormous boreal forest has trapped more than 300 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide, the Washington-based Natural Resources Defense Council said.

However, 10 to 13 percent of Canada’s boreal forest is covered by peatlands — wetlands with high levels of organic matter — and very little is known about them, said Garneau, research chair on peat ecosystems and climate change at the Universite du Quebec a Montreal.

Her work is supported by the province’s utility, Hydro-Quebec, whose dams — once the four additional hydropower plants on the Romaine River are turned on next year — are to supply 90 percent of Quebec’s power needs.

The data collected in this study should “serve the IPCC and the advancement of science in general” by helping to better peg the carbon footprint of flooded wilderness, Garneau told reporters.

The information is crucial as several new big hydroelectric projects are due to come online in the coming years, including in Canada, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Laos, Tajikistan and Zimbabwe.

“We’re creating artificial reservoirs around the world, but GHG [greenhouse gas] emissions from hydroelectricity are not well-accounted for,” university biologist Paul Del Giorgio said.

“There are some dams in tropical zones that emit as many greenhouse gases as coal plants,” due to the accelerated decomposition of drowned organic materials, the Argentine researcher said.

Del Giorgio and his students are complementing Garneau’s research by taking water samples from flooded lands behind dams that are analyzed in a field laboratory set up in Havre-Saint-Pierre’s town hall.

Both data sets are to be plugged into a complex set of equations to determine the volume of greenhouse gas emissions from dams.

The first results of their work are expected next year and are highly anticipated by climate scientists worldwide, Garneau said.

The IPCC desperately needs “to have better models for better predicting climate change,” she said.

Real estate agent and property developer JSL Construction & Development Co (愛山林) led the average compensation rankings among companies listed on the Taiwan Stock Exchange (TWSE) last year, while contract chipmaker Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) finished 14th. JSL Construction paid its employees total average compensation of NT$4.78 million (US$159,701), down 13.5 percent from a year earlier, but still ahead of the most profitable listed tech giants, including TSMC, TWSE data showed. Last year, the average compensation (which includes salary, overtime, bonuses and allowances) paid by TSMC rose 21.6 percent to reach about NT$3.33 million, lifting its ranking by 10 notches

Popular vape brands such as Geek Bar might get more expensive in the US — if you can find them at all. Shipments of vapes from China to the US ground to a near halt last month from a year ago, official data showed, hit by US President Donald Trump’s tariffs and a crackdown on unauthorized e-cigarettes in the world’s biggest market for smoking alternatives. That includes Geek Bar, a brand of flavored vapes that is not authorized to sell in the US, but which had been widely available due to porous import controls. One retailer, who asked not to be named, because

SEASONAL WEAKNESS: The combined revenue of the top 10 foundries fell 5.4%, but rush orders and China’s subsidies partially offset slowing demand Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) further solidified its dominance in the global wafer foundry business in the first quarter of this year, remaining far ahead of its closest rival, Samsung Electronics Co, TrendForce Corp (集邦科技) said yesterday. TSMC posted US$25.52 billion in sales in the January-to-March period, down 5 percent from the previous quarter, but its market share rose from 67.1 percent the previous quarter to 67.6 percent, TrendForce said in a report. While smartphone-related wafer shipments declined in the first quarter due to seasonal factors, solid demand for artificial intelligence (AI) and high-performance computing (HPC) devices and urgent TV-related orders

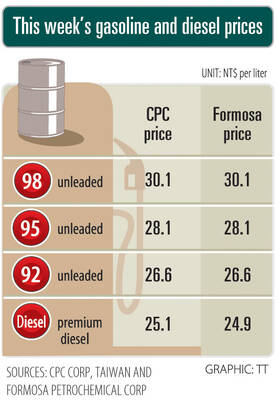

Prices of gasoline and diesel products at domestic fuel stations are this week to rise NT$0.2 and NT$0.3 per liter respectively, after international crude oil prices increased last week, CPC Corp, Taiwan (台灣中油) and Formosa Petrochemical Corp (台塑石化) said yesterday. International crude oil prices last week snapped a two-week losing streak as the geopolitical situation between Russia and Ukraine turned increasingly tense, CPC said in a statement. News that some oil production facilities in Alberta, Canada, were shut down due to wildfires and that US-Iran nuclear talks made no progress also helped push oil prices to a significant weekly gain, Formosa said