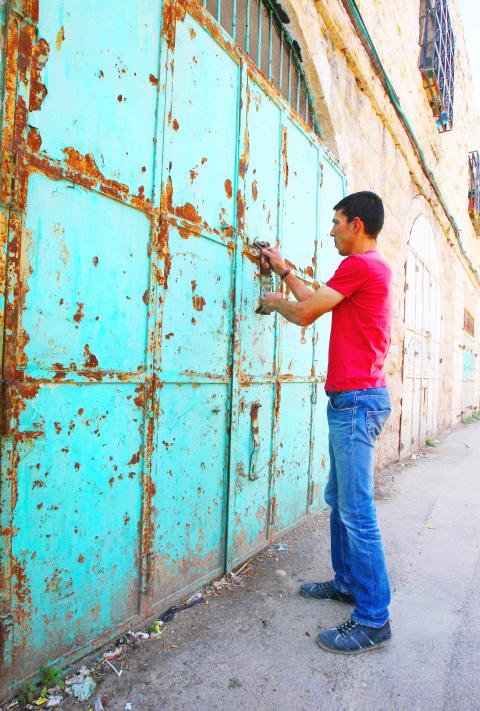

It took Mohammad Abu Halaweh a good 10 minutes to pry open the rusted metal doors of his butcher shop for the first time in two decades. He had the key, an old-fashioned iron number as big as his hand, but he had to press a sandaled foot against the door and leverage his body weight to yank off a second lock. A handful of curious children had gathered by the time he finally finished the job with the help of a hammer.

Inside, Abu Halaweh found what he had left back in 1994, when the Israeli military shuttered the shops of al-Sahla Street in the Old City of Hebron after a US-born Israeli doctor’s murderous rampage left 29 Muslim worshipers dead at the nearby Tomb of the Patriarchs. A scale covered in dust. The back room where the goats were killed, still a bit rank. An ancient ceiling fan. The shell of a refrigerator with empty meat hooks.

“This is the table where we used to chop the meat,” he said.

Photo: AFP

The reminiscing was cut short by an Israeli soldier, who ordered him to close up once again. It took Abu Halaweh, a bearded man of 50 in a gray jalabiya, almost as long to get the warped doors secured anew as it did to open them.

On June 19, the first Friday of Ramadan, the Palestinian mayor of Hebron announced that 70 of the 300-odd shops on al-Sahla Street could reopen. However, the Israeli military insisted that it had agreed to only seven, citing security concerns in a place where clashes with settlers are common. So al-Sahla, once a thriving marketplace off the storied Shuhada Street, remained a ghost town, as the Israeli human rights group B’tselem termed it in 2007.

LONG-TERM STRATEGY

Photo: AFP

“It’s a progressive process,” said Matthieu Desselas of the Hebron office of the International Committee of the Red Cross, which helped negotiate the deal. “The more shops are open, the more movement there will be. It’s a long-term strategy.”

Shway-shway, as they say in Arabic: slowly, slowly. Too slow, shop owners and residents complained. They said seven stores would not be enough to bring people back, especially since Israeli checkpoints surround the area and prevent Palestinian cars, and thus quantities of goods, from entering.

On Friday morning, a religious Jew with prayer fringes hanging over his shorts jogged through. Then came a group of European tourists in sun hats, cameras at the ready. New blue street signs, in Hebrew and English, but not Arabic, call it Emek Hebron Street.

Ghassan Abu Hadid, who has lived all his 32 years on this block, saw a different scene in his mind. The central taxi stand on one corner, buzzing with fares. Across the street, a stand filled with fresh produce. Behind the doors covered in peeling white paint, a home-appliance store. Next to it, a poultry market, and next to that a fragrant spice shop.

“You could barely walk here because it was so packed with people,” Abu Hadid recalled.

That was before Baruch Goldstein’s 1994 massacre at the tomb, which Muslims call the Ibrahimi Mosque, and before the 1997 Hebron Protocol that divided the city of 200,000 Palestinians and perhaps 700 Jews, leaving this section under the control of the Israeli military. Before the violent Second Intifada that stretched from 2000 to 2005, when Palestinians killed 22 Israelis in Hebron, including 17 security officers and 10-month-old Shalhevet Pass, according to B’tselem, and Israeli forces killed 88 Palestinians, nine of them minors.

“The declared commitment to free movement and unity of the city was rendered meaningless,” the group’s 2007 report says, citing a new curfew and street closings that led Palestinians to abandon more than 1,000 apartments above the shuttered storefronts.

“What was once the vibrant heart of Hebron has become a ghost town,” it says.

Back then, Abed Muhtaseb’s souvenir shop, across from the Jewish entrance to the revered tomb — which also draws international tourists — and Khaled Fakhouri’s pottery workshop next door were the only businesses open on al-Sahla Street, local residents said.

A year ago, the Red Cross persuaded the Israelis to permit a few more to unlock their doors: There is now a tiny cafe and two places that type up official documents, residents said, but they operate only a few hours a day for lack of traffic.

ONE STEP AT A TIME

Now, another handful got the go-ahead, including several owned by Abu Hadid’s extended family. He has put in a new tile floor and painted the walls pink in one storefront, planning to invest about US$8,000 to create a small grocery. On Friday, he examined the ancient, broken-down machines of the little factory where he used to help his grandfather grind wheat and local spices like zatar. And he put a cage of pigeons a few doors down: maybe a pet shop?

“I’m going to buy a fridge; I’m going to bring some shelves,” he said of the grocery-to-be.

As for the factory, “we’re going to renovate all these machines and get it back up and running,” he said, but warned: “If they don’t remove the checkpoints, this whole thing is for nothing.”

Tamar Toledano, a military spokeswoman, said she had no idea why the mayor had announced that 70 shops would reopen, raising false hopes.

“For now, it’s seven,” she said. “It’s a very complicated city. It’s little steps. It’s one step at a time.”

Abu Hadid took a little step on Friday. Actually, he took a seat, placing a plastic chair outside the shop, something he said Israeli soldiers had not allowed in a long time.

Additional reporting by Rami Nazzal

With an approval rating of just two percent, Peruvian President Dina Boluarte might be the world’s most unpopular leader, according to pollsters. Protests greeted her rise to power 29 months ago, and have marked her entire term — joined by assorted scandals, investigations, controversies and a surge in gang violence. The 63-year-old is the target of a dozen probes, including for her alleged failure to declare gifts of luxury jewels and watches, a scandal inevitably dubbed “Rolexgate.” She is also under the microscope for a two-week undeclared absence for nose surgery — which she insists was medical, not cosmetic — and is

CAUTIOUS RECOVERY: While the manufacturing sector returned to growth amid the US-China trade truce, firms remain wary as uncertainty clouds the outlook, the CIER said The local manufacturing sector returned to expansion last month, as the official purchasing managers’ index (PMI) rose 2.1 points to 51.0, driven by a temporary easing in US-China trade tensions, the Chung-Hua Institution for Economic Research (CIER, 中華經濟研究院) said yesterday. The PMI gauges the health of the manufacturing industry, with readings above 50 indicating expansion and those below 50 signaling contraction. “Firms are not as pessimistic as they were in April, but they remain far from optimistic,” CIER president Lien Hsien-ming (連賢明) said at a news conference. The full impact of US tariff decisions is unlikely to become clear until later this month

GROWING CONCERN: Some senior Trump administration officials opposed the UAE expansion over fears that another TSMC project could jeopardize its US investment Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) is evaluating building an advanced production facility in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and has discussed the possibility with officials in US President Donald Trump’s administration, people familiar with the matter said, in a potentially major bet on the Middle East that would only come to fruition with Washington’s approval. The company has had multiple meetings in the past few months with US Special Envoy to the Middle East Steve Witkoff and officials from MGX, an influential investment vehicle overseen by the UAE president’s brother, the people said. The conversations are a continuation of talks that

CHIP DUTIES: TSMC said it voiced its concerns to Washington about tariffs, telling the US commerce department that it wants ‘fair treatment’ to protect its competitiveness Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) yesterday reiterated robust business prospects for this year as strong artificial intelligence (AI) chip demand from Nvidia Corp and other customers would absorb the impacts of US tariffs. “The impact of tariffs would be indirect, as the custom tax is the importers’ responsibility, not the exporters,” TSMC chairman and chief executive officer C.C. Wei (魏哲家) said at the chipmaker’s annual shareholders’ meeting in Hsinchu City. TSMC’s business could be affected if people become reluctant to buy electronics due to inflated prices, Wei said. In addition, the chipmaker has voiced its concern to the US Department of Commerce