Leodegard Kagaba lifts his shirt to reveal an ugly scar on his belly left by a bullet that nearly killed him when Tutsi neighbors in Rwanda attacked him after accusing him of participating in the 1994 genocide.

“I have many scars, even in my heart,” he said. “The people who put those scars on me still live freely in Rwanda.”

Nearly two decades after the genocide, Kagaba and many of the other 9,000 Rwandans at the Nakivale refugee camp in Uganda say they are troubled by the looming prospect of forced repatriation back to Rwanda.

Hutu refugees say they fear reprisal attacks by Tutsis in Rwanda. During the genocide, at least 500,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus were killed in a campaign of mass murder orchestrated by Hutu extremists.

After the genocide, hundreds of thousands of Hutus — some charged with participating in the genocide, others simply afraid of reprisal killings — fled Rwanda and sought refuge across east and central Africa.

Many ended up in a sprawling settlement in Nakivale and some now regard the place as their home for life. In the settlement, the Rwandans have access to pasture for their cattle and many have set up successful businesses selling groceries or farm animals.

They say that political climate in Rwanda discourages them from leaving Nakivale. At least 92 percent of all Rwandan refugees in Uganda are Hutus, a UN refugee agency said.

Kagaba, an ethnic Hutu whose father and siblings were killed in 1994, said he would be harassed or worse in Rwanda because he saw atrocities committed by Tutsi soldiers who came to his village looking for genocide suspects.

Rwandan President Paul Kagame — an ethnic Tutsi — dismisses allegations that his country targets Hutus, saying those who played a role in the genocide should face the law.

However, groups such as Human Rights Watch — which the Rwandan government openly spars with — have long accused Kigali of using a genocide ideology law to target the regime’s critics. Independent journalists who have written critically about the history of the genocide have been threatened with jail terms. Many have fled.

Rwanda’s government said in a statement on Friday that “Rwandan refugees who hesitate to return home either lack enough information on the current situation in Rwanda or have developed significant ties with host countries.”

The 8,000 Rwandans who arrived in Uganda before 1998 have until the end of June to return home voluntarily. Uganda, which hosts the highest number of officially recognized Rwandan refugees, has published lists of those who are expected to return home soon.

In Nakivale, the Hutus who fled Rwanda at the end of the genocide spoke of a persistent witch hunt, saying sons can be harassed for their father’s crimes. Their grim opinion of life in Rwanda is reinforced by the accounts of refugees who returned to Rwanda and fled back to Uganda, saying they had been jailed on trumped-up charges and even tortured.

Some of the refugees freshly arriving from Rwanda claim persecution and want political asylum, said Lucy Beck, a spokeswoman for the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights’ (UNHCR) office in Uganda.

Belonging to a family seen in the community as having participated in the genocide carries a lifetime stigma, some refugees said, equating a Hutu’s return to Rwanda to committing suicide. Some Tutsi families are still eager to exact revenge on neighbors they believe killed their relatives, said Rajab Simpamanuka, a Hutu refugee who has lived in Nakivale since 2001.

Hamida Kabagwira, another Hutu refugee, said she will not forced to return to Rwanda.

“If they want it, they will have to come here and kill us. I will never find peace in Rwanda,” said Kabagwira, who was recently reunited with her husband, Shaban Mutabazi.

Mutabazi, who said he spent 16 years in a Rwandan jail for alleged genocide, fled to Uganda in January after serving his sentence because “after that everyone in my village saw me like an animal.”

UNHCR opposes forcible repatriations, but is powerless to stop them. A decision to forcibly evict refugees would be the responsibility of Ugandan officials, Beck said, adding that about 90 percent of refugees do not want to return.

Moses Watasa, a spokesman for the Ugandan department that manages refugees, said his office cannot be expected to rely on the refugees’ opinion of safety in Rwanda and that input from Rwanda’s government and the international community would be crucial.

Indonesia yesterday began enforcing its newly ratified penal code, replacing a Dutch-era criminal law that had governed the country for more than 80 years and marking a major shift in its legal landscape. Since proclaiming independence in 1945, the Southeast Asian country had continued to operate under a colonial framework widely criticized as outdated and misaligned with Indonesia’s social values. Efforts to revise the code stalled for decades as lawmakers debated how to balance human rights, religious norms and local traditions in the world’s most populous Muslim-majority nation. The 345-page Indonesian Penal Code, known as the KUHP, was passed in 2022. It

‘DISRESPECTFUL’: Katie Miller, the wife of Trump’s most influential adviser, drew ire by posting an image of Greenland in the colors of the US flag, captioning it ‘SOON’ US President Donald Trump on Sunday doubled down on his claim that Greenland should become part of the US, despite calls by the Danish prime minister to stop “threatening” the territory. Washington’s military intervention in Venezuela has reignited fears for Greenland, which Trump has repeatedly said he wants to annex, given its strategic location in the arctic. While aboard Air Force One en route to Washington, Trump reiterated the goal. “We need Greenland from the standpoint of national security, and Denmark is not going to be able to do it,” he said in response to a reporter’s question. “We’ll worry about Greenland in

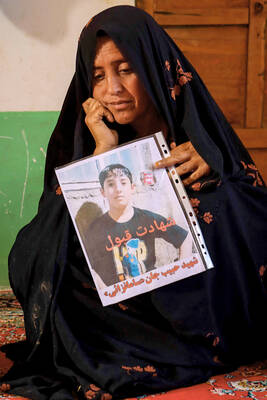

PERILOUS JOURNEY: Over just a matter of days last month, about 1,600 Afghans who were at risk of perishing due to the cold weather were rescued in the mountains Habibullah set off from his home in western Afghanistan determined to find work in Iran, only for the 15-year-old to freeze to death while walking across the mountainous frontier. “He was forced to go, to bring food for the family,” his mother, Mah Jan, said at her mud home in Ghunjan village. “We have no food to eat, we have no clothes to wear. The house in which I live has no electricity, no water. I have no proper window, nothing to burn for heating,” she added, clutching a photograph of her son. Habibullah was one of at least 18 migrants who died

Russia early yesterday bombarded Ukraine, killing two people in the Kyiv region, authorities said on the eve of a diplomatic summit in France. A nationwide siren was issued just after midnight, while Ukraine’s military said air defenses were operating in several places. In the capital, a private medical facility caught fire as a result of the Russian strikes, killing one person and wounding three others, the State Emergency Service of Kyiv said. It released images of rescuers removing people on stretchers from a gutted building. Another pre-dawn attack on the neighboring city of Fastiv killed one man in his 70s, Kyiv Governor Mykola