Scientists in the field of human fertility are coming under pressure to rein in maverick researchers whose experiments push ethical boundaries and caused public revulsion this week.

Critics say the lack of agreed standards is damaging the reputation of more mainstream researchers. While some countries have stringent guidelines backed up by enforceable legislation, others have none at all.

In those cases, given the will and the cash, anything goes. Eggs and sperm, donated in good faith, can be used in whatever research the scientists desire. Paul Serhal, director of the assisted conception unit at University College London, said fertility research was facing a critical question: "How do we prevent people doing monstrous things?"

The ethical crisis was thrown into vivid relief this week at a European fertility conference in Madrid when an Israeli-Dutch team reported they had matured eggs from an aborted foetus in the hope of finding a new source of eggs for couples needing treatment. Alarmed headlines were followed the next day with the news that a private fertility clinic in America had created bizarre hybrid human embryos called chimeras by merging male cells with female embryos.

Neither experiment would have been allowed in the UK, says the human fertility and embryology authority (HFEA). But the hybrid embryos had received ethical approval in the US and the foetal eggs research was approved in Israel. Both studies were presented in Madrid at the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology's annual meeting.

Most scientists are in no doubt that the studies, in particular the work on chimeric embryos, have delivered a blow to the public's confidence in fertility research.

"Studies of this nature are going to backfire on mainstream scientists who are doing genuine scientific work," said Serhal. "They will tarnish our image."

Only the HFEA can issue licenses for research on embryos in the UK. Certain areas are banned, such as placing a human embryo in an animal. The authority would not have approved the chimera work. "We think it's illegal," said Alison Cook of the HFEA. "The [HFEA] Act says that we are not allowed to alter the genetic material of any embryonic cell. We believe the spirit of the law would not allow you to put in an extra cell."

The prospect of a child being born from an egg from an aborted foetus would also be unacceptable to the authority because of the difficulty for the child coming to terms with its origins. All IVF (in vitro fertilization) clinics must consider above all the interests of the children they may help create. But the framework in the UK is not mirrored elsewhere.

"The country you most need to regulate is the one that's least likely to accept regulation -- the United States," said fertility expert Robert Winston at Hammersmith hospital, west London. "The problem is that they do not in general want central regulation, so you have different rules in different states."

Federal law washes its hands of embryo research by a refusal to fund any of it, so the work is left to private clinics and research institutes governed by the patchwork of state laws. A few states ban embryo research because of the passions evoked over abortion and the right to life. Elsewhere there is little restraint.

Norbert Gleicher, whose team created the chimera foetuses, is the founder and head of the for Human Reproduction, which has clinics in Chicago and New York. He appeared to have no trouble getting ethical approval for the work, which was intended to investigate a technique for curing genetic diseases.

Scientists are divided on how best to tackle the maverick element of fertility researchers or whether they even need to be tackled.

"The only way to rein them in is to have a body like the HFEA in different countries," said Serhal. "When you know there is someone breathing down your neck, you're going to think twice, if not more, before doing something stupid."

But there is no guarantee a global HFEA would be the answer. In the UK, some private clinics flout the fertility guidelines but do not seem to be penalized.

"They aren't even being threatened with having their licenses taken away," said Allan Templeton of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

By 2027, Denmark would relocate its foreign convicts to a prison in Kosovo under a 200-million-euro (US$228.6 million) agreement that has raised concerns among non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and residents, but which could serve as a model for the rest of the EU. The agreement, reached in 2022 and ratified by Kosovar lawmakers last year, provides for the reception of up to 300 foreign prisoners sentenced in Denmark. They must not have been convicted of terrorism or war crimes, or have a mental condition or terminal disease. Once their sentence is completed in Kosovan, they would be deported to their home country. In

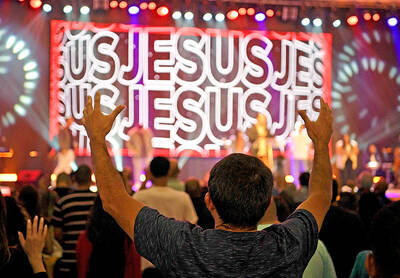

Brazil, the world’s largest Roman Catholic country, saw its Catholic population decline further in 2022, while evangelical Christians and those with no religion continued to rise, census data released on Friday by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) showed. The census indicated that Brazil had 100.2 million Roman Catholics in 2022, accounting for 56.7 percent of the population, down from 65.1 percent or 105.4 million recorded in the 2010 census. Meanwhile, the share of evangelical Christians rose to 26.9 percent last year, up from 21.6 percent in 2010, adding 12 million followers to reach 47.4 million — the highest figure

A Chinese scientist was arrested while arriving in the US at Detroit airport, the second case in days involving the alleged smuggling of biological material, authorities said on Monday. The scientist is accused of shipping biological material months ago to staff at a laboratory at the University of Michigan. The FBI, in a court filing, described it as material related to certain worms and requires a government permit. “The guidelines for importing biological materials into the US for research purposes are stringent, but clear, and actions like this undermine the legitimate work of other visiting scholars,” said John Nowak, who leads field

LOST CONTACT: The mission carried payloads from Japan, the US and Taiwan’s National Central University, including a deep space radiation probe, ispace said Japanese company ispace said its uncrewed moon lander likely crashed onto the moon’s surface during its lunar touchdown attempt yesterday, marking another failure two years after its unsuccessful inaugural mission. Tokyo-based ispace had hoped to join US firms Intuitive Machines and Firefly Aerospace as companies that have accomplished commercial landings amid a global race for the moon, which includes state-run missions from China and India. A successful mission would have made ispace the first company outside the US to achieve a moon landing. Resilience, ispace’s second lunar lander, could not decelerate fast enough as it approached the moon, and the company has