Taiwan in Time: Dec. 5 to Dec. 11

Shortly after noon on Dec. 10, 1949, Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) and his son Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國) finished their last meal in China. The elder Chiang’s mood was solemn as they headed to Chengdu’s military airport. Without saying a word, he boarded the plane to Taiwan.

By that time, the transfer of people, public property and military and governmental institutions to Taiwan was mostly complete. A day earlier, the Republic of China’s Executive Yuan held its 102nd meeting — its first in Taipei.

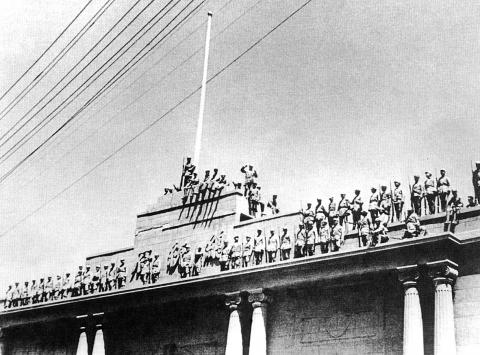

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) retreat to Taiwan in 1949 after losing the Chinese Civil War was a lengthier and more monumental, taking place over the course of more than a year with countless freight and air trips.

Before deciding on Taiwan, the KMT entertained the idea of retreating to western China. Many officials opposed the move, as it was too close to the rapidly advancing People’s Liberation Army, which knew the terrain well.

Chen Chin-chang (陳錦昌) writes in his book Chiang Kai-shek’s Retreat to Taiwan (蔣中正遷台記) that the decision to retreat to Taiwan was suggested by geographer and future Chinese Cultural University founder Chang Chi-yun (張其昀) in 1948.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Chang argued that Taiwan’s subtropical climate, abundant resources and advanced infrastructure left behind by the Japanese would be able to support a massive population influx. The Taiwan Strait would make it difficult for the People’s Liberation Army to mount an immediate attack, and the US would be more likely to protect such a strategic location.

Chang also believed that the people of Taiwan would welcome the “motherland” government after years of Japanese rule, and that it was relatively free of communist influence. The suppression of the 228 Incident a year previously would further deter people from causing unrest, making it a “stable” base for the KMT to prepare their counterattack.

THE BIG MOVE

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Chiang favored Chang’s proposal. Starting in August 1948, the Air Force started moving its equipment and institutions to Taiwan. This operation alone was a massive one. It took what is today the Air Force Institute of Technology 80 flights and three ships over four months to relocate. This did not include the other academies, training facilities, manufacturing plants, radio stations and military hospitals, which moved separately.

Chen writes that during this period, an average of 50 or 60 planes flew daily between Taiwan and China transporting fuel and ammunition.

By May 1949, the Air Force Command Headquarters was operating out of Taipei, having transported 1,138 officers, 814 pilots, 2,600 family members and about 6,000 tonnes of equipment and classified documents. The last group of pilots barely made it out of Shanghai as the Communists stormed the airport. Other military branches made their exits as key locations in China fell.

The official decision to transport artifacts from the National Palace Museum, National Central Library and Academia Sinica’s Institute of History and Philology to Taiwan was made on Nov. 10, 1948, but Chen writes that about 600 museum items were already moved in March. The National Central Museum and Beijing Library later joined the operation, resulting in a total of 5,522 large crates, with the first batch leaving Shanghai on Dec. 21.

Chen writes that the Navy sailors transporting the third batch boarded the ship with family members upon hearing that it was bound for Taiwan, and refused to disembark, greatly decreasing the number of crates it could carry.

Of course, not all the items could be saved. For example, the roughly 230,000 National Palace Museum items constituted just above 20 percent of the entire collection. But Chen writes that these were carefully selected.

In addition to books and documents, Institute of History and Philology director Fu Si-nian (傅斯年) also spearheaded a rush to persuade scholars to flee to Taiwan.

Chiang Kai-shek ordered a secret operation to transport gold from the Central Bank to Taiwan on Nov. 30, 1948. In the middle of the night, 774 boxes full of gold were manually transported from the bank to the pier. These operations continued until May of the following year. One ship sank, resulting in a loss of US$60 million and bank staff, and another one was held hostage by officers who almost succeeded in fleeing with the money to South America.

Other items transported included radio stations, boats, factory machinery, cars, wood, cloth and so on. About 1,500 ships carrying these items departed from Shanghai alone.

The number of people who arrived in Taiwan from China during this time is disputed. Chen’s book states that nearly 500,000 civilians made the trip between 1948 and 1950 along with an additional 500,000 military personnel for a total of 1 million, but other estimates have gone as high as 2.5 million.

Meanwhile, the Nationalist government hung on, moving from Chongqing to Chengdu on Oct. 28, 1949. On Nov. 30, the Air Force was given 10 days to transport the remaining Nationalist officials and their family out of China. Chiang Kai-shek remained until the last minute, never to return.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

This month the government ordered a one-year block of Xiaohongshu (小紅書) or Rednote, a Chinese social media platform with more than 3 million users in Taiwan. The government pointed to widespread fraud activity on the platform, along with cybersecurity failures. Officials said that they had reached out to the company and asked it to change. However, they received no response. The pro-China parties, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), immediately swung into action, denouncing the ban as an attack on free speech. This “free speech” claim was then echoed by the People’s Republic of China (PRC),

Exceptions to the rule are sometimes revealing. For a brief few years, there was an emerging ideological split between the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) that appeared to be pushing the DPP in a direction that would be considered more liberal, and the KMT more conservative. In the previous column, “The KMT-DPP’s bureaucrat-led developmental state” (Dec. 11, page 12), we examined how Taiwan’s democratic system developed, and how both the two main parties largely accepted a similar consensus on how Taiwan should be run domestically and did not split along the left-right lines more familiar in

Many people in Taiwan first learned about universal basic income (UBI) — the idea that the government should provide regular, no-strings-attached payments to each citizen — in 2019. While seeking the Democratic nomination for the 2020 US presidential election, Andrew Yang, a politician of Taiwanese descent, said that, if elected, he’d institute a UBI of US$1,000 per month to “get the economic boot off of people’s throats, allowing them to lift their heads up, breathe, and get excited for the future.” His campaign petered out, but the concept of UBI hasn’t gone away. Throughout the industrialized world, there are fears that

Most heroes are remembered for the battles they fought. Taiwan’s Black Bat Squadron is remembered for flying into Chinese airspace 838 times between 1953 and 1967, and for the 148 men whose sacrifice bought the intelligence that kept Taiwan secure. Two-thirds of the squadron died carrying out missions most people wouldn’t learn about for another 40 years. The squadron lost 15 aircraft and 148 crew members over those 14 years, making it the deadliest unit in Taiwan’s military history by casualty rate. They flew at night, often at low altitudes, straight into some of the most heavily defended airspace in Asia.