On the morning of July 13, 1949, hundreds of secondary school students from China’s Shandong Province were rounded up by the Nationalist military at the drilling grounds of the military base on Penghu Island.

These refugees of the Chinese Civil War had just arrived with their schools’ educators, reportedly being promised to be able to continue their education while also undergoing military training. But the military commanders in Penghu had other ideas.

There are many versions of what transpired next, which would years later be known as the 713 Penghu Incident (七一三澎湖事件). The accounts mentioned below were taken from students who were present at the time.

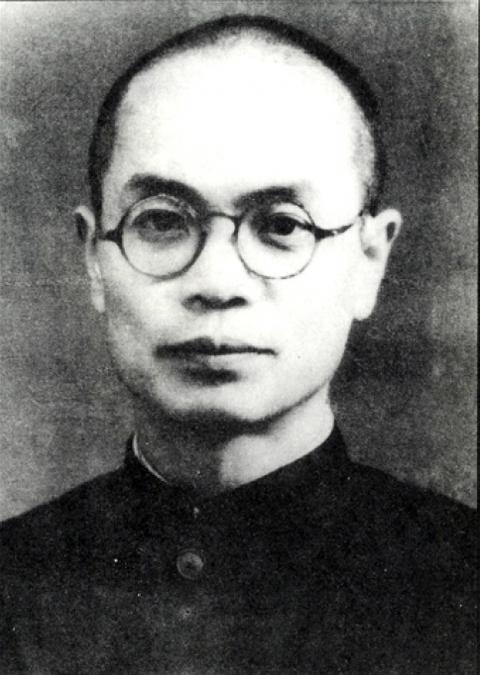

Photo: Luo Tien-pin, Taipei Times

Tang Ke-chung (唐克忠) says in an oral history interview with Academia Sinica that he already had a bad feeling upon arrival as the male students were isolated in a military compound and forbidden from leaving. The teachers and female students were nowhere to be seen.

Huang Tuan-li (黃端禮) says when they asked where the teachers were, the officer told him, “You are all soldiers now. Studying will not help you fight the Communists.”

“They even confiscated our textbooks,” he adds.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Once at the drilling grounds, the military started their forced conscription of the students into army units, reportedly to bolster their thin ranks. Surrounded by armed troops and machine guns on the rooftops, Tang says nobody resisted at first — until the they started targeting those who were underage.

“That did not sit well with us,” Tang says. “We started telling them that we came here to study, or at least half-study and half-train. And it all started from there.”

Tang and another student stepped up onto the flag-raising platform and led the crowd, chanting slogans in protest. Several soldiers rushed toward them with bayonets, stabbing Tang in the buttocks and the thigh and the other student in the arm. Huang confirms these events.

“They tied us up and took us away, and we do not know what happened afterward,” Tang says. He heard that many students were arrested later and more were put into sacks and thrown into the ocean, but he cannot confirm it since he was locked up for the next three months.

Huang says once they saw all the blood from the protest leaders’ wounds, they were scared into submission with no further incident. There has been recent controversy about whether the military actually opened fire on the students — some historians state that they did — but all seven direct witness accounts examined only mention the stabbings.

FICTIONAL CONFESSIONS

The real aftermath came later, as school principals Chang Min-chih (張敏之) and Tsou Chien (鄒鑑) attempted to report the incident to the authorities and save the students.

Unhappy with the principals’ resistance, the military arrested more than 100 students — now soldiers — around the end of July, “forcing” confessions of being Communist spies out of them, leading to the arrest of Chang and Tsou.

Taiwan was already under martial law back then, and any suspicion of being a Communist could lead to automatic execution. The saying was, “Rather kill 100 people wrongfully than let one person get away.”

Sun Hsu-chen (孫序振) was one of the students arrested without warning. He notes that when he was brought to the ocean, he was afraid that he would be put into a sack and tossed into the sea — the same practice that was mentioned by Tang.

Sun says that he was repeatedly tortured — with beatings, electrocution and even “fake” executions where the bullets would miss intentionally — while the military told him exactly what to say to implicate Chang and Tsou.

“Otherwise, how would we at such a young age know anything about the organization of the Communists?” Sun says.

Ho Chen-yu (賀振宇) says that since none of their confessions matched, the military made up a unified fictional Communist spy organization and even assigned specific positions and roles to all the arrested students.

When Sun finally gave in, he found that even his confession was already written for him. Fortunately, he and about 60 other students were released and re-organized into an army unit. About 40 others were brought to Taipei to stand trial. When they landed, spectators pelted them with garbage and called them traitors.

Chu Fu-shan (初福山), only 16 years old, was one of them. He recalls crying in court and refusing to admit to being a spy. Surprisingly he and another student were spared. Others were not so lucky.

On Dec. 12, an article with the harrowing title, You Cannot Escape, Seven Communist Spies Executed Yesterday (你們逃不掉的, 昨續槍決匪諜七名) appeared on page four of the Central Daily News (中央日報), accusing Chang, Tsou, and five students of planning to incite military rebellion in Penghu.

“Citizens glared at the accused angrily, and as the bullets rang and the bandits fell, everyone in the audience expressed their gratification,” the article stated.

“We hereby warn all Communist spies that Taiwan is a steel fortress, and your military subversion tricks will not work here,” another article concluded.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.