Taiwan in Time: Dec. 7 to Dec. 13

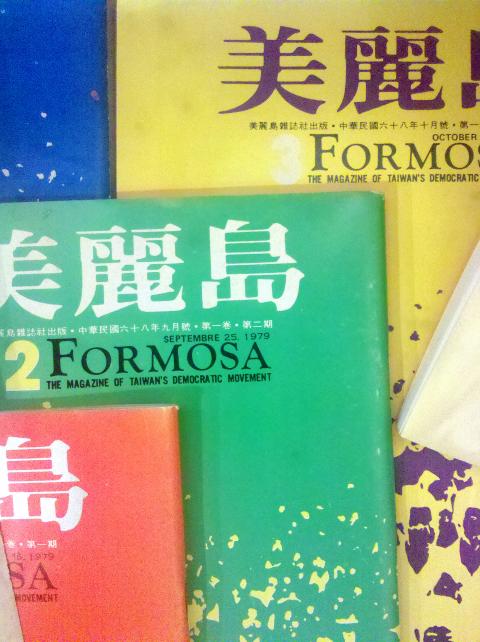

The night of Dec. 12, 1979 was a restless one for the staff of Formosa Magazine (美麗島雜誌), as they gathered in a building in Taipei where several of them lived.

Photo: Chu Pei-hsiung, Taipei Times

Almost all of them would go on to become major Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) political players in the future, but for now, they were wanted criminals.

Two days previously, on Human Rights Day, the magazine, published by dangwai (黨外, “outside the party”) politicians opposing the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) one-party rule, organized a pro-democracy rally in Kaohsiung. The KMT sent troops and police to surround and intimidate the protesters, and things soon turned violent. Official injury numbers initially showed 183 officers and no civilians, the latter figure later increased to 50.

Accounts of what actually happened changed over time, with perceptions today being more sympathetic to the dangwai than what was indicated in the KMT-controlled media.

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Today’s popular version of events is that the police repeatedly closed in on the protesters and used tear gas, which caused them to retaliate despite calls for calm by protest leaders. This came to be known as the Kaohsiung Incident, also called the Formosa Incident.

The next day, the National Security Bureau and Taiwan Garrison Command announced that they would arrest those who were responsible for the incident — namely the dangwai politicians.

In an oral history of the incident published by Academia Sinica, former vice president and Formosa Magazine editor Annette Lu (呂秀蓮) says for safety concerns she and current Kaohsiung mayor Chen Chu (陳菊) were staying with fellow magazine staff Lin Yi-hsiung (林義雄), Shih Ming-te (施明德) and Linda Gail Arrigo.

Lu says she fell asleep while Arrigo kept contact with the outside through telephone. When the phone line was cut, Arrigo knew something was wrong and barricaded the doors with furniture.

Lu remembers Chen jumping off the second floor balcony, distracting the officer pursuing Shih, who eventually got away. The rest of them were arrested. Arrigo was deported, while the others, along with four other opposition leaders were accused of sedition, tried by a military court and sentenced to terms ranging from 12 years to life imprisonment.

THEN AND NOW

Today, the incident is regarded as a crucial moment in Taiwan’s democratization. Though it would be another eight years until opposition parties were officially allowed, this event is often considered a sign of the KMT’s weakening grip on sole power of the country.

But back then, most media outlets portrayed the rally organizers as riot inciters who had planned the violence and were serious threats to a stable, “democratic” society.

Consider this passage from the 1980 book The Complete Story of the Formosa Incident (美麗島事件始末): “This is a very satirical tragedy in the history of Taiwanese democracy, as the violence was perpetrated by people who have been calling loudly for democracy.”

Almost each newspaper printed letters from “patriotic” readers denouncing the dangwai’s actions, as well as interviews with local officials, wounded officers, celebrities and so on. Most accounts also state that the officers didn’t fight back when attacked and praised their noble actions.

One article features an officer who lost several teeth in the incident. He reportedly refused the consolation money offered by the government.

Unable to speak, he wrote on a piece of paper, “What’s the use of giving me money? I just want our country to survive … I hope the government will stop tolerating these inhumane conspirators.”

Nothing could be more symbolic than the sailor who stood in the face of the protesters with his hands held high, tears on his face, singing loudly the patriotic song Plum Blossom (梅花), even continuing when he was attacked.

“I am Chinese, I love my country,” he reportedly yelled.

Of course, each side has their own story to tell, but the various commentaries calling the incident an attack on a “free and democratic” country is deeply ironic, as martial law was still in effect, and it was in fact the lack of democracy that led to the founding of the magazine.

Although opposition parties were still banned, the KMT appeared to become more lenient as it allowed dangwai politicians to run for the National Assembly in 1969. They were gearing up for the 1978 legislative elections when the US severed relations with Taiwan. In response, the KMT suspended all electoral activities and announced that emergency measures would be taken against those who gathered illegally or held demonstrations.

Their only means of entering politics cut off, the dangwai turned to political activism. Formosa was formed as the voice of the dangwai, and celebrated its first issue with a banquet at the Mandarina Crown Hotel while it was surrounded by taunting protesters led by members of a pro-KMT magazine. It was a rocky start, and it took a long time before things got easier.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Taiwan has next to no political engagement in Myanmar, either with the ruling military junta nor the dozens of armed groups who’ve in the last five years taken over around two-thirds of the nation’s territory in a sprawling, patchwork civil war. But early last month, the leader of one relatively minor Burmese revolutionary faction, General Nerdah Bomya, who is also an alleged war criminal, made a low key visit to Taipei, where he met with a member of President William Lai’s (賴清德) staff, a retired Taiwanese military official and several academics. “I feel like Taiwan is a good example of

March 2 to March 8 Gunfire rang out along the shore of the frontline island of Lieyu (烈嶼) on a foggy afternoon on March 7, 1987. By the time it was over, about 20 unarmed Vietnamese refugees — men, women, elderly and children — were dead. They were hastily buried, followed by decades of silence. Months later, opposition politicians and journalists tried to uncover what had happened, but conflicting accounts only deepened the confusion. One version suggested that government troops had mistakenly killed their own operatives attempting to return home from Vietnam. The military maintained that the

“M yeolgong jajangmyeon (anti-communism zhajiangmian, 滅共炸醬麵), let’s all shout together — myeolgong!” a chef at a Chinese restaurant in Dongtan, located about 35km south of Seoul, South Korea, calls out before serving a bowl of Korean-style zhajiangmian —black bean noodles. Diners repeat the phrase before tucking in. This political-themed restaurant, named Myeolgong Banjeom (滅共飯館, “anti-communism restaurant”), is operated by a single person and does not take reservations; therefore long queues form regularly outside, and most customers appear sympathetic to its political theme. Photos of conservative public figures hang on the walls, alongside political slogans and poems written in Chinese characters; South

Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (蔣萬安) announced last week a city policy to get businesses to reduce working hours to seven hours per day for employees with children 12 and under at home. The city promised to subsidize 80 percent of the employees’ wage loss. Taipei can do this, since the Celestial Dragon Kingdom (天龍國), as it is sardonically known to the denizens of Taiwan’s less fortunate regions, has an outsize grip on the government budget. Like most subsidies, this will likely have little effect on Taiwan’s catastrophic birth rates, though it may be a relief to the shrinking number of