Even though Taipei is often considered one of the most vegan-friendly places in Asia, the country’s offerings often aren’t obvious nor clear-cut for someone who doesn’t know Chinese, much less a first time visitor who only has four days in the city and wants to get on with their sightseeing without being constantly worried about accidentally ingesting or purchasing something that contains animal products.

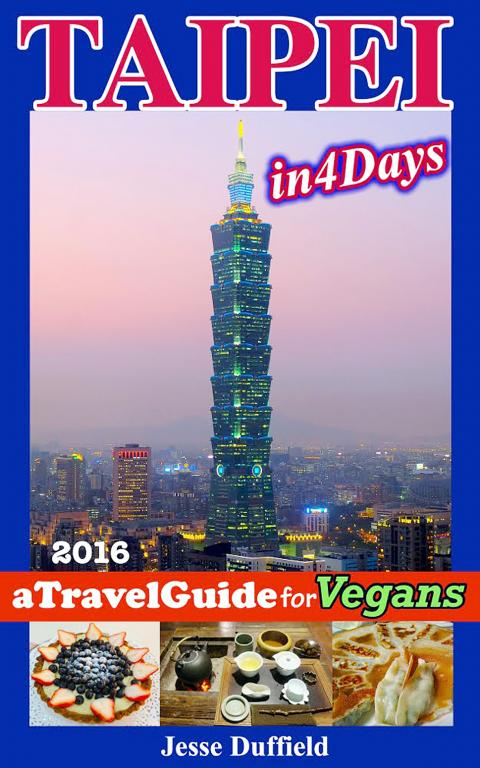

Even though Jesse Duffield, author of the e-book Taipei in 4 Days: A Travel Guide for Vegans lauds Taiwan’s strict labeling policies, vegetarian-friendly attitudes and abundance of meatless options, he also details the difficulties of trying to follow a strict vegan diet here. Language barriers aside, many restaurants claim to serve vegan food but actually serve egg and milk products, and often the wait staff themselves don’t know the difference between veganism and vegetarianism.

Consider this entry on Minder Vegetarian (明德素食園): “Contrary to claims made by staff and even on their Web site, it’s not all vegan.” Duffield also mentions the existence of “completely vegetarian restaurants” that are “almost completely non-vegan.”

That’s where this book comes in handy, guiding the reader from how to read the food labeling system to recommending where to get vegan food and which destinations you should bring your own lunch because of the lack of options.

Duffield says he has personally visited every restaurant and location, and from his writing you can tell that he’s lived in Taiwan for an extended period of time.

Although the book teaches its readers the Chinese characters for “vegetarian food” before they learn how to say ni hao, knowing your vegan ins and outs isn’t enough to survive in Taipei.

Duffield provides detailed information such as transportation, hotels, postal services, safety, shopping, the mess of the country’s Romanization systems (to go to Chinan Temple you have to get off at Zhinan Station) and even how to use Taiwan’s ATMs, which can be very confusing at first.

There’s a sprinkling of vegan info here and there — such as where to get vegan food at the airport or while you’re shopping for electronics at Guanghua Market (光華商場).

There’s also an extensive history and religion section, and of course, every book written about Taiwan must at least try to explain the dreaded complicated political history of the nation, which isn’t an easy task.

Duffield does a decent job here – his overview is a bit confusing at first, but it gets the point across that Taiwan is a de facto independent country and explains the Republic of China’s existence well. The politics are better explained later with separate entries on the various entities and figures that have contributed to the current situation. Some sections, especially the final part about Taiwan and former president Lee Teng-hui’s (李登輝) relationship with Japan may be too in-depth for a guidebook.

The religion/spiritual group section is viewed in a vegetarian/vegan context, as we learn interesting tidbits. For example, if a vegetarian restaurant serves egg products, it’s likely run by followers of I Kuan Tao (一貫道).

On to the tours, which are divided into four outings in different parts of Taipei and New Taipei City. The suggested itineraries combine sightseeing and eating, and has detailed information including recommended visiting times before going into detail about each location. Each general area is followed by vegan dining options nearby, all of which would show up on a customized map which links to Google Maps, making navigation easy. The use of the color of the MRT line while referring to each station is also a clever touch.

The destinations are well-researched and interspersed with bits of vegan information, such as how the rhino horn displays in the National Palace Museum come with a warning about not supporting the trade of endangered animals, and a discussion on whether stinky tofu is vegan or not.

The restaurant descriptions are very helpful — they tell the reader what’s vegan, what to avoid, what atmosphere to expect, whether the staff is knowledgeable about veganism, and so on.

One problem with the tours is the organization of the entries — it takes a while to get used to as each section is organized differently, and some food options accompany the destination while others are grouped into a dining section after the general area sight listings. However, it’s mostly because of the layout. Every section and subsection uses a very similar black serif title font, which makes it hard to distinguish at first whether the reader is still in the restaurant section or has moved on to the next tour area. Also, some of the photographs are too dark, and they could all be larger or more graphically appealing within the page. While it is a practical e-book, it’s just not very pretty to look at — somewhat disappointing for a book about food.

Overall, the book gets the job done as a comprehensive tool for the visiting vegan. For those who want to travel beyond Taipei, Duffield is in the process of updating the earlier and more extensive version of this book, Taiwan, a Travel Guide for Vegans, which covers northern Taiwan and Taroko Gorge.

Most heroes are remembered for the battles they fought. Taiwan’s Black Bat Squadron is remembered for flying into Chinese airspace 838 times between 1953 and 1967, and for the 148 men whose sacrifice bought the intelligence that kept Taiwan secure. Two-thirds of the squadron died carrying out missions most people wouldn’t learn about for another 40 years. The squadron lost 15 aircraft and 148 crew members over those 14 years, making it the deadliest unit in Taiwan’s military history by casualty rate. They flew at night, often at low altitudes, straight into some of the most heavily defended airspace in Asia.

Beijing’s ironic, abusive tantrums aimed at Japan since Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi publicly stated that a Taiwan contingency would be an existential crisis for Japan, have revealed for all the world to see that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) lusts after Okinawa. We all owe Takaichi a debt of thanks for getting the PRC to make that public. The PRC and its netizens, taking their cue from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), are presenting Okinawa by mirroring the claims about Taiwan. Official PRC propaganda organs began to wax lyrical about Okinawa’s “unsettled status” beginning last month. A Global

Taiwan’s democracy is at risk. Be very alarmed. This is not a drill. The current constitutional crisis progressed slowly, then suddenly. Political tensions, partisan hostility and emotions are all running high right when cool heads and calm negotiation are most needed. Oxford defines brinkmanship as: “The art or practice of pursuing a dangerous policy to the limits of safety before stopping, especially in politics.” It says the term comes from a quote from a 1956 Cold War interview with then-American Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, when he said: ‘The ability to get to the verge without getting into the war is

Like much in the world today, theater has experienced major disruptions over the six years since COVID-19. The pandemic, the war in Ukraine and social media have created a new normal of geopolitical and information uncertainty, and the performing arts are not immune to these effects. “Ten years ago people wanted to come to the theater to engage with important issues, but now the Internet allows them to engage with those issues powerfully and immediately,” said Faith Tan, programming director of the Esplanade in Singapore, speaking last week in Japan. “One reaction to unpredictability has been a renewed emphasis on