For Zadie Smith, criticism is a bodily pleasure, not an abstracted mental operation. Reading, like eating, caters to her ravenous but discriminating appetite: she finds the essence of Kafka in a sliver of words from his diary, carved, she says, as thin as Parma ham and containing the creator’s “marbled mark.” She doesn’t need a snack when watching a film, because her eyes are feeding on the images: Brief Encounter is, for her, a chunk of Wensleydale cheese, inimitably English. The critical arguments in which Smith engages are as vital and as potentially violent as sexual wrestling matches, and in an essay on Katharine Hepburn she recalls that she ejected two lovers from her bed — on separate occasions, I should explain — because they disagreed with her about the relationship between Hepburn and Spencer Tracy in Adam’s Rib.

Smith consumes books and films, by which I mean that she absorbs them, seizing on them with all her acute, avid senses. When she was 14, her mother gave her Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God to read. The aim was to raise Zadie’s biracial consciousness, though the result, vividly described in the first essay in this volume, was more intense and more transformative. “I inhaled that book,” Smith recalls (like an oenophile, she reads through her nostrils). It took her three hours to finish the volume and she expressed her critical judgment on it in a fit of grateful, ecstatic tears. When her mother called her to dinner, she took the book to the table, not because she intended to discuss it but because it was in itself a meal, offering her communion with the nutritious blood and body of its author.

This is not the way critics are supposed to comport themselves. Smith’s enthusiasm is almost shocking; she breaks the rules established by the black-gowned, gruel-blooded nerds in universities who murder books by dissecting them, reduce poems and novels to texts which are no more than snarled networks of verbal signals and revenge themselves on the literature they secretly hate by writing badly about it.

Reading for Smith is a mind-changing, life-giving, soul-saving affair and her criticism has a missionary urgency. In a long and brilliant study of Middlemarch — which persuaded me to change my mind about a novel I’ve always considered tiresome — she avows that “love enables knowledge, love is a kind of knowledge.” She is referring to George Eliot’s Spinozistic union of emotional experience and moral perception, but she might also be articulating her own creed as critic. The intellectual revelations Smith purveys derive from and are ignited by her love for the books she has read.

In her first novel, White Teeth, she called tradition “a sinister analgesic,” as deeply embedded and degenerate as dental caries. She has changed her mind about that, because for her, as the title of her collection implies, criticism is a record of the mind’s growth and its game-playing versatility. Her review of a collection of E.M. Forster’s radio book chat exactly defines Smith’s newly congenial attitude to the literary past. Forster made her the gift of his talent — she used Howards End as the model for her most recent novel On Beauty — and she is repaying his generosity, just as he settled his debts to his predecessors in those broadcast talks.

He refused, Smith notes, to call what he did “literary criticism, or even reviewing”; he was making “recommendations,” like a “chatty librarian leaning over the counter.” His modesty was “peculiarly English,” a sly way of appeasing the country’s hostility to culture. Smith has fewer misgivings about her own impassioned intelligence, but she is engaged in the same activity.

Her task, however, is harder than Forster’s was, because as well as disarming popular anti-intellectualism, she has to confront the over-intellectualized commissars of academic criticism. In a superb essay on Nabokov and Barthes, she explores the battling claims of writer versus reader, creator versus theorist, acknowledging that the dispute is being fought out inside her. As a student, she delighted in Barthes’ obituary for authorship, which licensed readers to rewrite texts and use them as alibis for indulging political gripes and sexual kinks.

Surely this libertarian practice was preferable to Nabokov’s snooty expectation that readers should be worshippers, in awe of the author’s genius? Smith’s experience as a novelist persuaded her, once again, to change her mind and her essay restores faith in “the difficult partnership between reader and writer.”

Hence her knowing use of a theological word when she says that in Middlemarch Eliot makes “literary atonement” for our isolation by filling her book “with more objects of attention than a novel can comfortably hold.” That thronging abundance is the delight of White Teeth. The narrator of Ian McEwan’s Atonement worries that art can’t atone for the errors and crimes of art, because its solutions are fictional and illusory; Smith at her most fervent has no such doubts. An author, in her view, is not a despotic Nabokovian god. In a wonderful aside about the indeterminacy of meaning in Shakespeare, she remarks that “the idea of a literary genius is a gift we give ourselves, a space so wide we can play in it forever.” This makes me want to throw a ball to her and bounce up and down in the hope of catching it when she retaliates.

Changefulness is Smith’s theme throughout this collection. A lecture delivered at the New York Public Library remembers how she changed her voice, advancing from the glottally stopped argot of Willesden to the posher, plummier vowels she imbibed at Cambridge — though her aim, as she admits, was to be polyvocal, to alternate between those idioms, and she praises US President Barack Obama, “a genuinely many-voiced man,” for possessing the same flexibility. (Her homage to the new president dates from soon after his election, when her “novelist credo” led her to hope that his command of different vocal registers would lead to “a flexibility in all things.” A year later, Obama is beginning to look merely slippery, flexing himself by inconclusively running on the spot.)

Elsewhere, Smith praises fluidity, another name for the same virtue. She finds it in the languid grace with which Robert de Niro opens a fridge door in Mean Streets, in the “elastic” expressiveness of Claire Danes in Shopgirl as against the “unmoving, waxy face” of the Botoxed Steve Martin and in the athleticism of Raymond Carver’s prose. For a writer, fluency is “the ultimate good omen”: if the words are pouring out, they’re probably good words. Its opposite is fixity, a calcification that sets the mind in stone and prepares the body for rigor mortis. This Smith detects in Wordsworth when he reneges on the revolutionary idealism of his youth, in the elderly bigotry of Kingsley Amis and in the defeatism of all those who, having reached the age of 50, stop reading contemporary fiction. These justified digs made me check on the state of my own stiffening joints and hardening arteries, my calcium-encrusted dogmas and sclerotic orthodoxies. It’s good to know that, while my body rusts, I can keep my mind stretched and nimble by reading Zadie Smith.

From the last quarter of 2001, research shows that real housing prices nearly tripled (before a 2012 law to enforce housing price registration, researchers tracked a few large real estate firms to estimate housing price behavior). Incomes have not kept pace, though this has not yet led to defaults. Instead, an increasing chunk of household income goes to mortgage payments. This suggests that even if incomes grow, the mortgage squeeze will still make voters feel like their paychecks won’t stretch to cover expenses. The housing price rises in the last two decades are now driving higher rents. The rental market

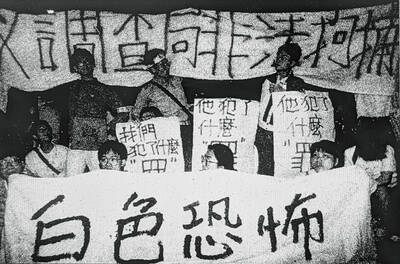

July 21 to July 27 If the “Taiwan Independence Association” (TIA) incident had happened four years earlier, it probably wouldn’t have caused much of an uproar. But the arrest of four young suspected independence activists in the early hours of May 9, 1991, sparked outrage, with many denouncing it as a return to the White Terror — a time when anyone could be detained for suspected seditious activity. Not only had martial law been lifted in 1987, just days earlier on May 1, the government had abolished the Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of National Mobilization for Suppression of the Communist

When life gives you trees, make paper. That was one of the first thoughts to cross my mind as I explored what’s now called Chung Hsing Cultural and Creative Park (中興文化創意園區, CHCCP) in Yilan County’s Wujie Township (五結). Northeast Taiwan boasts an abundance of forest resources. Yilan County is home to both Taipingshan National Forest Recreation Area (太平山國家森林遊樂區) — by far the largest reserve of its kind in the country — and Makauy Ecological Park (馬告生態園區, see “Towering trees and a tranquil lake” in the May 13, 2022 edition of this newspaper). So it was inevitable that industrial-scale paper making would

Hualien lawmaker Fu Kun-chi (傅?萁) is the prime target of the recall campaigns. They want to bring him and everything he represents crashing down. This is an existential test for Fu and a critical symbolic test for the campaigners. It is also a crucial test for both the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and a personal one for party Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫). Why is Fu such a lightning rod? LOCAL LORD At the dawn of the 2020s, Fu, running as an independent candidate, beat incumbent Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) lawmaker Hsiao Bi-khim (蕭美琴) and a KMT candidate to return to the legislature representing