Four-year old Daniel Santos da Silva and his older brother Diego Mota dos Santos, 10, heard their first gunshots in April. Their father was shot in a dispute over land on a cattle ranch near the Brazilian town of El Dorado, in the Amazonian state of Para. The boys heard he was taken to hospital, but they have not seen him since.

The ranch is called Espirito Santo, Holy Spirit, though goodwill to all men is hard to find there. Heavily armed guards protect the thousands of cattle that roam its lush pastures and the hacienda-style complex built on a hill at the farm’s center, complete with swimming pool.

Daniel and Diego live on the muddy fringe of the farm in a hastily erected collection of palm frond-roofed huts to shield them and a hundred-odd other families from regular tropical downpours. They are squatters, but squatters rights are rarely observed in Para.

Espirito Santo and thousands of farms like it raise cattle on Amazonian pasture that was once rainforest. The farms are huge, and so is their impact. The cattle business is expanding rapidly in the Amazon, and now poses the biggest threat to the 80 percent of the original forest that still stands. Where loggers have made inroads to the edge of the forest in the states of Para and Mato Grosso, farmers have followed.

A report released on Monday from Greenpeace details a three-year investigation into these cattle farms and the global trade in their products, many of which end up on sale in Europe. Meat from the cattle is canned, packaged and processed into convenience foods. Hides become leather for shoes and trainers. Fat stripped from the carcasses is rendered and used to make toothpaste, face creams and soap. Gelatin squeezed from bones, intestines and ligaments thickens yogurt and makes chewy sweets.

Greenpeace says it has lifted the lid on this trade to expose the “laundering” of cattle raised on illegally deforested land.

The environment campaign group wants Brazilian companies that buy cattle to boycott farms that have chopped down forest after an agreed date. To get the industry onside, it is seeking pressure from multinational brands that source their products in Brazil, and, ultimately, from their customers. Three years ago, a similar exposure of the trade in illegally grown Brazilian soya brought a rapid response from the industry, and a moratorium on soya from newly deforested farms that still holds.

Last month, I joined Greenpeace on an undercover visit to the cattle farming heartland around the town of Maraba, deep inside the Amazon region. While saving the rainforest is a fashionable cause in faraway countries such as the UK, in Maraba it is a provocative and even dangerous ideal.

Many people in Maraba work at the slaughterhouse perched on a hill that overlooks the town. The facility is owned by the Brazilian firm Bertin, one of the companies targeted by Greenpeace for buying cattle from farms linked to illegal deforestation. After slaughter, Greenpeace says Bertin ships the meat, hides and other products to an export facility in Lins, near Sao Paolo. From there, they are shipped all over the world. The firm is Brazil’s second-largest beef exporter and the largest leather exporter. It is also the country’s largest supplier of rawhide dog chews.

Bertin denies taking cattle from Amazon farms associated with deforestation. The company says it “makes permanent investments in initiatives that minimize impacts resulting from its activities” and that it seeks “to be a reference in the sector.” It says it has already blacklisted 138 suppliers for “irregularities.”

Brazilian government records obtained by Greenpeace show that 76 cattle were shipped to the Bertin slaughterhouse in Maraba from Espirito Santo farm in May 2008. Another 380 were received in January this year.

Standing on Espirito Santo’s shady veranda, Oscar Bollir, the farm manager, insists they do nothing wrong.

Under Brazilian law, such farms inside the Amazon region must retain 80 percent of the original forest within their legal boundary. So why is there pasture for as far as the eye can see? The farm is very big, Bollir says, and most of the required forest is on the other side of some low-slung hills in the distance.

The squatters on the farm, part of a political movement to settle landless people on illegally snatched farmland, are troublemakers, he says. “They don’t want land, they just want trouble. They want to take all the farms.” Earlier that day, he says, he and his men had been forced to visit a neighboring farm where squatters had killed cattle. Unlike the previous incident on Espirito Santo, when Daniel and Diego’s father was shot alongside several others, Bollir says, this time there had been no trouble.

He adds that he is aware of environmental concerns, but that his priority is to produce food and jobs. “Why are these other countries looking at Brazil and telling us what to do?”

The next day, Greenpeace investigators flew over Espirito Santo — the group has a single-engine plane donated by an anonymous British benefactor. Bollir’s promised bonanza of forest was not there. GPS data combined with satellite images show that just 20 percent to 30 percent of the farm is forested. A local lawyer also reported that during the nearby dispute over the killed cattle, three squatters had been shot and injured.

The Greenpeace report identifies dozens of farms like Espirito Santo that it says break the rules across Para and Mato Grosso to supply Bertin and other slaughter companies. Campaigners say there are probably hundreds or even thousands more.

Cheap pasture from clearing and seeding rainforest is very attractive to farmers without easy access to the expensive agrochemicals and intensive land management techniques used in more developed countries. Within a few years, the planted pasture becomes overrun with native grass, unsuitable for cattle. Many farmers then take the cheap option and knock down adjoining forest to start again, leaving swaths of unproductive deforested land in their wake.

Andre Muggiati, a campaigner with Greenpeace Brazil based in the Amazon town of Manaus, says efforts to protect the forest in frontier regions such as Para are crippled by a lack of effective governance. Government inspections are inadequate and many farms are not even registered so checks cannot be carried out. Casual violence and intimidation are common. “It’s totally unregulated and many people behave as if the law does not apply to them. It’s like the old US wild west,” he says.

Illegal deforestation is not the only problem: farms are regularly exposed as using slave labor, and, like many tropical forest regions, there are regular and violent clashes over land ownership.

The problem is clear a three-hour flight across the patchy forest from Maraba, where a clearing on the side of the river is home to a few hundred Parakana people, a tribe with no contact with the outside world until 1985.

Greenpeace can only reach the village because its plane is equipped to land on the sluggish water, but cattle farmers are steadily intruding. Hundreds of farms have been set up in the surrounding reserve, and they are not welcome.

“Since the invaders arrived there have been many problems,” says Itanya, the village chief. Food is harder to find, he says, and discontent is growing. “If the government [doesn’t] find a solution we will solve it ourselves. We know how to make poison arrows and we are ready to kill people.” It is not an idle threat: in 2003 the bodies of three farmers were discovered in the jungle not far from the village. Itanya says it was the work of a neighboring group.

“We asked them many times to stay away,” Kokoa, the chief of the neighboring group, said through an interpreter. “They wouldn’t, so one time we said to them that you will never go back and you will stay here forever. We killed them. We are proud that we defended our land.”

When life gives you trees, make paper. That was one of the first thoughts to cross my mind as I explored what’s now called Chung Hsing Cultural and Creative Park (中興文化創意園區, CHCCP) in Yilan County’s Wujie Township (五結). Northeast Taiwan boasts an abundance of forest resources. Yilan County is home to both Taipingshan National Forest Recreation Area (太平山國家森林遊樂區) — by far the largest reserve of its kind in the country — and Makauy Ecological Park (馬告生態園區, see “Towering trees and a tranquil lake” in the May 13, 2022 edition of this newspaper). So it was inevitable that industrial-scale paper making would

Asked to define sex, most people will say it means penetration and anything else is just “foreplay,” says Kate Moyle, a psychosexual and relationship therapist, and author of The Science of Sex. “This pedestals intercourse as ‘real sex’ and other sexual acts as something done before penetration rather than as deserving credit in their own right,” she says. Lesbian, bisexual and gay people tend to have a broader definition. Sex education historically revolved around reproduction (therefore penetration), which is just one of hundreds of reasons people have sex. If you think of penetration as the sex you “should” be having, you might

Hualien lawmaker Fu Kun-chi (傅?萁) is the prime target of the recall campaigns. They want to bring him and everything he represents crashing down. This is an existential test for Fu and a critical symbolic test for the campaigners. It is also a crucial test for both the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and a personal one for party Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫). Why is Fu such a lightning rod? LOCAL LORD At the dawn of the 2020s, Fu, running as an independent candidate, beat incumbent Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) lawmaker Hsiao Bi-khim (蕭美琴) and a KMT candidate to return to the legislature representing

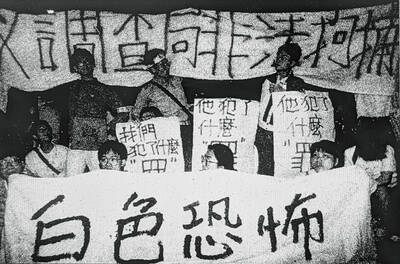

July 21 to July 27 If the “Taiwan Independence Association” (TIA) incident had happened four years earlier, it probably wouldn’t have caused much of an uproar. But the arrest of four young suspected independence activists in the early hours of May 9, 1991, sparked outrage, with many denouncing it as a return to the White Terror — a time when anyone could be detained for suspected seditious activity. Not only had martial law been lifted in 1987, just days earlier on May 1, the government had abolished the Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of National Mobilization for Suppression of the Communist