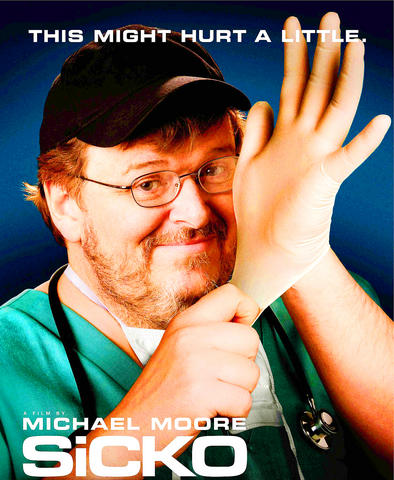

In making SiCKO, his new documentary about US health care, Michael Moore assumed the public knows it needs improvement but doesn't fully realize why. So he argues that the US' health care suffers badly in comparison to other countries - costing twice as much for results that are no better and often worse - and basically asks, "Don't we deserve better?"

"I really want to make a contribution to the national debate on this issue," Moore said. The movie's national release Friday was limited after it sold out in all 44 of its previews.

Moore's audience is likely receptive to his diagnosis, if not his prescription "to take the profit motive out of health care." In a CBS News/New York Times poll last year, 34 percent said the health care system should be completely rebuilt and 90 percent wanted at least fundamental change. In last month's Kaiser Family Foundation poll, health care was the top domestic priority for presidential candidates, second overall to Iraq.

PHOTOS: AP AND REUTERS

SiCKO already has spun off Scrubs for SiCKO, with doctors' and nurses' groups advocating universal, single-payer health care (www.guaranteedhealthcare.org), and www.FreeMarketCure.com, with articles and short films favoring private-market solutions. YouTube, Oprah.com and other sites are soliciting tales of woe.

Moore has been rave-reviewed on foxnews.com, pirated on the Internet and warned of possible federal prosecution for taking Sept. 11 rescue workers to Cuba for medical care they couldn't afford at home.

Even many of his allies have bemoaned the Cuba trip for hurting their cause more than helping it. As always, Moore exaggerates, overly generalizes, ignores opposing viewpoints and raises doubts about how much he should be believed.

Several years of solid research on US health care can help viewers draw their own conclusions about Moore's contentions.

Do we really spend twice as much on health care as the rest of the developed world?

Not twice as much as everyone. But at a per-capita cost of US$6,102 in 2004, US health care more than doubled the expenditures in 19 of 29 other developed countries in Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OCED) data.

On the individual level, health insurance premiums rose by 58.5 percent, after inflation, from 2000 to 2006, while wages increased by just 1.7 percent.

That extra spending often doesn't even improve health, said Mark McClellan, who directed the Food and Drug Administration and then Medicare-Medicaid in 2002-07. "We know that much of the spending is going to treatments that are unnecessary or lead to medical errors, so we're not getting nearly as much value as we should."

But don't the high taxes in other countries cancel out the differences?

Those figures include both private and public (tax) expenditures. Americans even spend more tax dollars on health care than the other OCED countries, where taxes pay for universal coverage. We spend 10 percent more than high-taxing France and about US$10 for every US$7 in the OCED median.

Does the US health system really rank 37th in the world, as Moore says?

Only in a seven-year-old report by the World Health Organization. It ranked the US first in the health services it delivers, but below 50th for overspending and making those with low incomes pay so much.

OCED comparisons are more useful. The Commonwealth Fund regularly compares six countries - the US, Canada, the UK, Australia, New Zealand and Germany - and consistently ranks the US last overall.

Ailing system

In the 2007 report's nine categories, the only US ranking above fifth was number one for the "right care," reflecting American superiority in acute illness and injury. But five US rankings were last - access, equity, efficiency, safe care and "long, healthy and productive lives."

For example, 34 percent of sicker Americans reported medical, drug or lab errors in the last two years, and the New England Journal of Medicine has concluded Americans get the recommended treatments only about half the time.

Even a UnitedHealthcare ad in March conceded the US health system "that was designed to make you feel better often just makes things worse." As Ezekiel Emanuel wrote in the May 16 Journal of the American Medical Association, "If a politician declares that the US has the best health care system in the world today, he or she looks clueless."

Is Cuba's socialized health care as good as Moore makes it out to be?

Not at all. It puts a relatively high priority on health, and prevents infectious diseases well for a resource-poor country, but the resources it lacks are basic. Shortages of syringes, antibiotics, aspirin, latex gloves, even light bulbs are widely described.

Although true of Cuba, "socialized medicine" is far more rare than the term is used. The UK is the only large, wealthy country where the doctors and other providers work for the government. Germany and others with universal coverage don't even use single-payer, where government replaces insurance companies.

Are Americans' life expectancy and infant-mortality rates as bad as Moore says?

They're well below average. Defenders of for-profit medicine point out that much of the problem is social justice rather than medical, since US rates are worst among minorities and those with low incomes.

Even so, Americans ranked 40th in 2005 with 6.4 infant deaths per 1,000 live births, nearly double the rates of France and Iceland. White infants alone wouldn't make the top 30.

Raw death rates aren't as useful as an OCED stat that asks, how many deaths would ideal health care have prevented? The US tied for 15th out of 19 countries in nine-year-old data, 53 percent behind France.

Costs are too high, but aren't most Americans happy with health care quality?

Health Affairs found 40 percent of Americans satisfied with their health care system in 2000. Seven countries were over 70 percent. Polling suggests the numbers haven't improved.

In a 2004 Commonwealth Fund survey, patients ranked US doctors last among the five English-speaking countries for listening, explaining and spending enough time with patients.

One problem is that doctors are rewarded "in our market-based system for a visit or a procedure, not for patients' health," said Carol Diamond, who directs the philanthropic Markle Foundation's health program. Moore said his biggest surprise was that other countries reward doctors for "keeping people well."

Expensive health

The result, as Jack Wennberg's Dartmouth University research shows, is that higher amounts of medical service generate not only higher costs, but also worse health. Giving the medical care to people who don't need it removes the benefit from risk-benefit equations.

"Up to one-third of our health care dollars are squandered on ineffective, sometimes unwanted, often unproven procedures," Wennberg told Maggie Mahar in her recent book, Money-Driven Medicine: The Real Reason Health Care Costs So Much.

Don't other countries have long waiting lists and rationing?

Yes, most other countries have longer waits to see specialists and have elective surgery. On the other hand, patients elsewhere are more apt to see doctors promptly when they're sick.

Cost tends to be the main US rationing tool. In the six-country study, sicker Americans were most likely to forgo medicine, doctor visits, tests and medical treatments because of cost. Most of the 51 percent who skipped at least one in 2005 had insurance.

Moore praises Canada, but aren't they always coming here for better health care?

Anecdotes aside, a 2002 Health Affairs study found "barely detectable" numbers of Canadians going to US border cities for treatment. In a 1996 Canadian survey, only 20 of 18,000 respondents crossed the border specifically for care.

Research comparing their quality favors Canada just slightly, Open Medicine reported in April. Even so, "Nobody in the US seriously proposes recreating the British or Canadian systems here," wrote The New Republic's Jonathan Cohn, author of Sick: The Untold Story of America's Health Care Crisis - And the People Who Pay the Price.

Do insurance companies really cancel sick people's policies?

California officials recently fined Blue Cross of California US$1 million for just that, and is investigating other companies.

It found violations in each of 90 randomly selected cancellations, of about 1,000 a year. But California insurers can't cancel policies without proving intent to deceive, which Money magazine said is not true of Ohio.

Is it true that in Canada, France and Great Britain, "Anyone can go to the hospital, can go to a doctor and never have to worry about paying a bill," as Moore says?

No. Even in the socialized UK, there are some out-of-pocket expenses, but Americans have more than most.

Americans spent US$5 out of pocket for every US$3 spent in OCED's median country in 2004. In 2005, 34 percent of sicker US adults spent at least $1,000 out of pocket, more than twice the percentage anywhere else in the six-country study.

The insured family selling all its possessions to pay medical bills in SiCKO is also extreme but plausible. "Medical debt is surprisingly common," Access Project officials wrote last year in Health Affairs, "affecting about 29 million nonelderly Americans, with and without health insurance." That's roughly one in six, and medical bills sent 44 percent of them through all or most of their savings.

As Cohn wrote in his review, "SiCKO got a lot of the little things wrong. But it got most of the big things right."

On the Net: www.michaelmoore.com.

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

It’s a bold filmmaking choice to have a countdown clock on the screen for most of your movie. In the best-case scenario for a movie like Mercy, in which a Los Angeles detective has to prove his innocence to an artificial intelligence judge within said time limit, it heightens the tension. Who hasn’t gotten sweaty palms in, say, a Mission: Impossible movie when the bomb is ticking down and Tom Cruise still hasn’t cleared the building? Why not just extend it for the duration? Perhaps in a better movie it might have worked. Sadly in Mercy, it’s an ever-present reminder of just