The 100th anniversary of Albert Einstein's annus mirabilis has not passed quietly. Newspapers, magazines and TV documentaries have all trumpeted the year in which Einstein published five papers rethinking the laws of time and space. This year also marks the 50th anniversary of the former patent clerk's death.

Yet lying between these two dates is a less well-known anniversary. It is 74 years since Einstein attended the only seance of his life. What could have persuaded Einstein to attend such an unscientific event?

By 1930 Einstein was one of the most famous people on the planet. His general theory of relativity (with a little help from E=mc2) had thrust him into the spotlight as the foremost proponent of the new scientific age. Knowing of his plans to leave Germany, the world's leading universities tried to tempt him to their campuses.

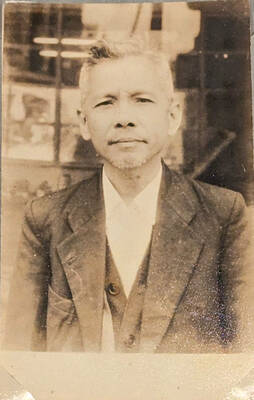

PHOTO: AP

It was the offer from the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena, on the outskirts of Los Angeles, that proved most enticing, thanks to their top astronomer, Edwin Hubble, who had seen distant galaxies streaking away from Earth through his 250cm telescope. Here was proof that the universe was expanding, an observation that refuted Einstein's view of the universe as a fixed sphere. Intrigued, he and his wife traveled west in 1931.

In Pasadena, the 51-year-old Einstein found solace in the company of one of the locale's most notorious gadflies, the author Upton Sinclair. The Michael Moore of his time, Sinclair's The Jungle (1906) had exposed the unsanitary conditions and labor exploitation rife in Chicago's meat-packing industry. The book caused a national outcry and so horrified former president Theodore Roosevelt that he reputedly threw his sausages out of the White House window.

Sinclair went on to write further jeremiads against big business, yet his latest project was quite different. He had become obsessed with extra-sensory perception and had written a book, Mental Radio (1930), about experiments he had conducted that seemed to prove telepathy's existence.

Sinclair had sent Einstein a copy of Mental Radio before his arrival in the US. Einstein was a great admirer of Sinclair's previous, muckraking works and offered to write an open-minded, if ultimately non-committal, preface.

The two became the closest of friends. Einstein wrote telegrams of support for the striking workers that Sinclair championed, and Sinclair provided Einstein with a break from celebrity and science, taking him to the cinema to see All Quiet on the Western Front, which had been banned in Germany as pacifist propaganda.

Other than in the preface to Mental Radio, Einstein had never professed any kind of interest, let alone belief, in supernatural beings or extra-sensory powers. "Even if I saw a ghost," he once said, "I wouldn't believe it." But Sinclair was excited by the prospect and thought that this was his best chance to convert Einstein to his cause.

Count Roman Ostoja was a muscular, dark-eyed man who claimed to be a Polish aristocrat, although he was really from Cleveland, Ohio. He had been working the west coast under the stage name of Nostradamus and gained plaudits for being buried underground in a coffin for three hours. He claimed to have studied under "occult masters" in India and Tibet and had wowed Sinclair with his mind-reading.

Nevertheless, Ostoja must have been slightly overawed by what was now suggested to him. Sinclair wanted Ostoja to conduct a seance at his house to which would be invited not only Einstein, but Richard Tolman, soon to be chief scientific adviser to the Manhattan Project, and Paul Epstein, Caltech's professor of theoretical physics. When the evening came, Sinclair addressed the learned crowd, warning them not to panic. At a previous seance Ostoja had managed to levitate a table while in a trance.

Helen Dukas, Einstein's secretary, remembered being "frightened to death" by the proceedings. Ostoja went into a cataleptic trance and began mumbling incomprehensible words. Each of the guests was invited to ask him questions. Silence fell, the table shook, "and then," remembered Dukas, "nothing happened." Sinclair was distraught. He grumbled about "non-believers" being present at the table.

Curiously enough, when Einstein was asked, years later, about his beliefs in the telepathic experiments of Dr JB Rhine, then studying parapsychology at Duke University, he stressed his scepticism in strictly scientific terms. All of Rhine's experiments had reported that psi-forces did not decline with distance, unlike the four known forces of nature -- gravity, electromagnetism, the strong force and the weak force.

"This suggests to me a very strong indication that a non-recognized source of systematic errors may have been involved," Einstein wrote.

Indeed it was scientific fallacies such as these, rather than drawing room seances, that could most reliably send a shiver up Einstein's spine. When he was confronted with seemingly illogical phenomena in quantum mechanics -- where particles appear to communicate instantaneously with each other -- he chose to label it in terms more suited to one of Sinclair's seances as "spooky action-at- a-distance."

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name