On the night of his 12th wedding anniversary, Andrew Friedman was terrified.

This brilliant surgeon and researcher at Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School feared that he was about to lose everything -- his career, his family, the life he'd built -- because his boss was coming closer and closer to the truth: For the past three years, Friedman had been faking -- actually making up -- data in some of the respected, peer-reviewed studies he had published in top medical journals.

``It is difficult for me to describe the degree of panic and irrational thought that I was going through,'' he would later tell an inquiry panel at Harvard.

On this night, March 13, 1995, he had been ordered in writing by his department chair to clear up what appeared to be suspicious data.

But Friedman didn't clear things up.

``I did something which was the worst possible thing I could have done,'' he testified.

He went to the medical record room, and for the next three or four hours he pulled out the permanent medical files of a handful of patients. Then he covered up his lies, scribbling in the information he needed to support his study.

``I created data. I made it up. I also made up patients that were fictitious,'' he testified.

Friedman's wife met him at the door when he came home that night. He wept uncontrollably. The next morning he had an emergency appointment with his psychiatrist.

But he didn't tell the therapist the truth, and his lies continued for 10 more days, during which time he delivered a letter, and copies of the doctored files, to his boss. Eventually he broke down, admitting first to his wife and psychiatrist, and later to his colleagues and managers, what he had been doing.

Friedman formally confessed, retracted his articles, apologized to colleagues and was punished. Today he has resurrected his career, as senior director of clinical research at Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical Inc, a Johnson & Johnson company.

His case, recorded in a 2.1m-high stack of documents at the Massachusetts Board of Registration in Medicine, tells a story of one man's struggle with power, lies and the crushing pressure of academia.

The story itself is more common than most people might realize.

Allegations of research misconduct reached record highs in the United States last year -- the Department of Health and Human Services received 274 complaints, which was 50 percent higher than 2003 and the most since 1989, when the federal government established the program to deal with scientific misconduct.

Chris Pascal, director of the federal Office of Research Integrity, said its 28 staffers and US$7 million annual budget haven't kept pace with the allegations. The result: Only 23 cases were closed last year. Of those, eight individuals were found guilty of research misconduct. In the past 15 years, the office has confirmed about 185 cases of scientific misconduct.

Research suggests this is but a small fraction of all the incidents of fabrication, falsification and plagiarism. In a survey published June 9 in the journal Nature, about 1.5 percent of 3,247 researchers who responded admitted to falsification or plagiarism. One in three admitted to some type of professional misbehavior.

Some cases have made headlines:

Eric Poehlman was convicted this year of fabricating research data to obtain a US$542,000 federal grant while working as a professor at the University of Vermont College of Medicine.

Also this year, Gary Kammer, a Wake Forest University rheumatology professor and leading lupus expert, was found to have made up two families and their medical conditions in grant applications to the National Institutes of Health. He has resigned from the university and has been suspended from receiving federal grants for three years.

In November, 2004, federal officials found that Ali Sultan, an award-winning malaria researcher at the Harvard School of Public Health, had plagiarized text and figures, and falsified his data -- substituting results from one type of malaria for another -- on a grant application for federal funds to study malaria drugs.

While recent cases have been high-profile, they are not unprecedented.

In 1974, William Summerlin, a top-ranking Sloan-Kettering Cancer Institute researcher, used a marker to make black patches of fur on white mice in an attempt to prove his new skin graft technique was working.

His case prompted Al Gore, then a young Democratic congressman, to hold the first congressional hearings on the issue.

``At the base of our involvement in research lies the trust of American people and the integrity of the scientific exercise,'' said Gore at the time. As a result of the hearings, Congress passed a law in 1985 requiring institutions that receive federal money for scientific research to have some system to report rulebreakers.

David Wright, a Michigan State University professor who has researched why scientists cheat, said there are four basic reasons: some sort of mental disorder; foreign nationals who learned somewhat different scientific standards; inadequate mentoring; and, most commonly, tremendous and increasing professional pressure to publish studies.

His inability to handle that pressure, Friedman testified, was his downfall. At the time he started cheating, Friedman's reputation was tremendous and his work groundbreaking.

``And it was almost as though you're on a treadmill that starts out slowly and gradually increases in speed. And it happens so gradually you don't realize that eventually you're just hoping you don't fall off,'' he told a magistrate during a state hearing in 1995. ``You're sprinting near the end and taking it all you can not to fall off.''

He testified that he was working 80 to 90 hours a week, with patient visits, surgery, meetings and more. He did seek help, both from a psychiatrist, who counseled him to cut back, and from his boss, who demanded Friedman increase his research and refused to reduce Friedman's patient load.

As good as Friedman was as a doctor, surgeon and researcher, he was actually a lousy cheater. One thing that brought about his demise, in fact, was that the initials he used for fictitious patients were the same as those of residents and faculty members in his program.

Friedman was repentant once caught, and he resigned from his positions at both Brigham and Women's, and Harvard.

From the last quarter of 2001, research shows that real housing prices nearly tripled (before a 2012 law to enforce housing price registration, researchers tracked a few large real estate firms to estimate housing price behavior). Incomes have not kept pace, though this has not yet led to defaults. Instead, an increasing chunk of household income goes to mortgage payments. This suggests that even if incomes grow, the mortgage squeeze will still make voters feel like their paychecks won’t stretch to cover expenses. The housing price rises in the last two decades are now driving higher rents. The rental market

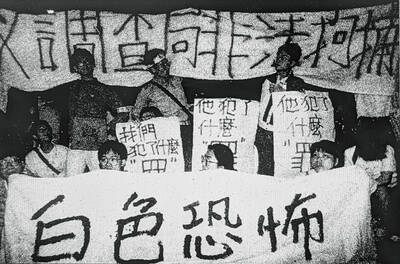

July 21 to July 27 If the “Taiwan Independence Association” (TIA) incident had happened four years earlier, it probably wouldn’t have caused much of an uproar. But the arrest of four young suspected independence activists in the early hours of May 9, 1991, sparked outrage, with many denouncing it as a return to the White Terror — a time when anyone could be detained for suspected seditious activity. Not only had martial law been lifted in 1987, just days earlier on May 1, the government had abolished the Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of National Mobilization for Suppression of the Communist

When life gives you trees, make paper. That was one of the first thoughts to cross my mind as I explored what’s now called Chung Hsing Cultural and Creative Park (中興文化創意園區, CHCCP) in Yilan County’s Wujie Township (五結). Northeast Taiwan boasts an abundance of forest resources. Yilan County is home to both Taipingshan National Forest Recreation Area (太平山國家森林遊樂區) — by far the largest reserve of its kind in the country — and Makauy Ecological Park (馬告生態園區, see “Towering trees and a tranquil lake” in the May 13, 2022 edition of this newspaper). So it was inevitable that industrial-scale paper making would

Hualien lawmaker Fu Kun-chi (傅?萁) is the prime target of the recall campaigns. They want to bring him and everything he represents crashing down. This is an existential test for Fu and a critical symbolic test for the campaigners. It is also a crucial test for both the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and a personal one for party Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫). Why is Fu such a lightning rod? LOCAL LORD At the dawn of the 2020s, Fu, running as an independent candidate, beat incumbent Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) lawmaker Hsiao Bi-khim (蕭美琴) and a KMT candidate to return to the legislature representing