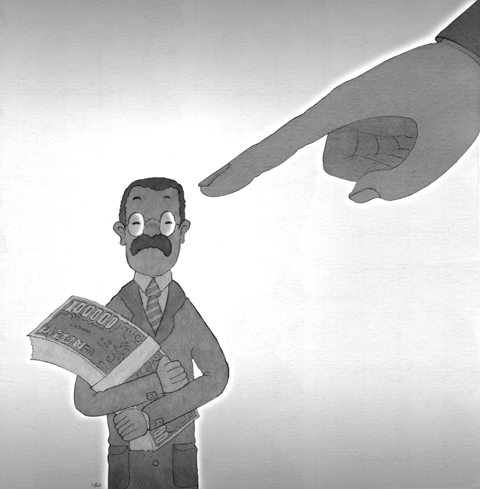

Just what is fair pay? Plato said the income of the highest paid in society should never amount to more than five times that of the lowest paid. For British Prime Minister David Cameron, a ratio of 20 times between the highest and lowest paid is the maximum tolerable — in the public sector, at least. He has yet to state what the comparable private sector figure should be.

In the corporate world the figures speak for themselves. The pay gap between the boardroom and the shop floor of Britain’s top firms has almost doubled in size over the last decade. The chief executives of the UK’s 100 largest companies overall earned 81 times the average pay of fulltime workers last year, against a ratio of just 47 nine years earlier. Hardly a Platonic relationship.

It is, of course, in banking that the scale of rewards has become most out of kilter. And it hasn’t escaped the public’s notice that only a year or so ago Britain’s banks were saved from collapse by an unprecedented injection of billions of pounds of taxpayers’ money.

My worry is that skepticism about the world of high finance is spilling over into other sectors: The public is questioning the very nature of business and its benefits for the wider community. Why, the public will ask, should we continue to support a business structure where bosses simply see the aim as enriching themselves, with little regard for the environment or society generally?

The public is also starting to grasp that the misalignment of bonuses with corporate strategies is threatening businesses’ very survival. The cult of shareholder value has fostered a short-term focus, which has led to excessive risk-taking and contributed to business collapse. In some industries long-term strategy and long-term sustainability have been relegated to minor roles.

So what should right-minded executives, directors and owners of companies do? I believe there are three basic principles they must follow to avert a complete loss of public trust. First, ensure that pay policy is embedded within a strategy for delivering long-term sustainable corporate growth. Bonuses may, on occasion, be justified. But done badly, executive rewards can propel companies towards financial ruin if the incentives are misaligned with the purpose of the business.

Enron was a clear example — its corporate culture was based on a single performance metric — maximizing share price — without regard for employees, customers or other stakeholders. More recently, the failure of Lehman Brothers has been linked to outsized executive pay deals. Analysis by the Harvard Law School found that the top executive team extracted US$1 billion in cash bonuses and equity sales between 2000 and 2008, suggesting their pay deals encouraged them to take excessive risk.

This leads to the second principle, which is that there must be a close link between the potential rewards and the risks an employee is taking on behalf of the firm. For those who take long-term risks, such as building a mortgage book with a 10-year maturity, it seems sensible that bonus payments should be over a similar time. Bonuses could be paid annually in one-tenth parts, retained in a fund until retirement or paid only in the employer’s shares.

The third principle is the most important — that there should be a better balance between the rewards given to the owners and the employees of a business. No single employee can deliver success alone. Every hotshot trader or hard-working manager depends on an overall strategy hammered out by their company, access to capital and market intelligence, corporate reputation and back-office support.

According to the New York authorities, Wall Street banks will pay US$20 billion in bonuses and retain US$55 billion in profits this year. Does this really reflect the contribution those individuals have made? This is a question that a company’s remuneration committee, which has all the facts about the business at its fingertips, should be able to answer.

There is hope. Some bank executives have waived their bonuses. Moreover, investors are attempting to clamp down. Five company reports on pay were voted down by investors last year.

Not all bonus payments are bad. The fact that 70,000 partners in the John Lewis Partnership [the British department store and supermarket chain is structured as a cooperative] will share in a £151 million (US$219 million) bonus pool is seen as a fair and proportionate reward. But if the public can see no link between a bonus and performance, they are entitled to object.

Excessive bonuses are a market failure and it ought to be possible to solve them through market pressure. But owners must show they are prepared to take action. Any crackdown on public sector bonuses should send a clear message to the private sector: address excessive pay or it will be addressed for you.

Plato was right — there is an implicit agreement in society that the rich cannot simply exploit their power to unreasonably enrich themselves.

Charles Tilley is chief executive of the Chartered Institute of Management Accountants.

They did it again. For the whole world to see: an image of a Taiwan flag crushed by an industrial press, and the horrifying warning that “it’s closer than you think.” All with the seal of authenticity that only a reputable international media outlet can give. The Economist turned what looks like a pastiche of a poster for a grim horror movie into a truth everyone can digest, accept, and use to support exactly the opinion China wants you to have: It is over and done, Taiwan is doomed. Four years after inaccurately naming Taiwan the most dangerous place on

Wherever one looks, the United States is ceding ground to China. From foreign aid to foreign trade, and from reorganizations to organizational guidance, the Trump administration has embarked on a stunning effort to hobble itself in grappling with what his own secretary of state calls “the most potent and dangerous near-peer adversary this nation has ever confronted.” The problems start at the Department of State. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has asserted that “it’s not normal for the world to simply have a unipolar power” and that the world has returned to multipolarity, with “multi-great powers in different parts of the

President William Lai (賴清德) recently attended an event in Taipei marking the end of World War II in Europe, emphasizing in his speech: “Using force to invade another country is an unjust act and will ultimately fail.” In just a few words, he captured the core values of the postwar international order and reminded us again: History is not just for reflection, but serves as a warning for the present. From a broad historical perspective, his statement carries weight. For centuries, international relations operated under the law of the jungle — where the strong dominated and the weak were constrained. That

The Executive Yuan recently revised a page of its Web site on ethnic groups in Taiwan, replacing the term “Han” (漢族) with “the rest of the population.” The page, which was updated on March 24, describes the composition of Taiwan’s registered households as indigenous (2.5 percent), foreign origin (1.2 percent) and the rest of the population (96.2 percent). The change was picked up by a social media user and amplified by local media, sparking heated discussion over the weekend. The pan-blue and pro-China camp called it a politically motivated desinicization attempt to obscure the Han Chinese ethnicity of most Taiwanese.