The recent news that two-thirds of adults in the US are overweight or obese — and the number continues to grow — brings to mind a question that has bothered me since the 1970s: Why aren’t we all starving?

It was not that long ago that experts were predicting that our skyrocketing human population would outstrip its food supply, leading directly to mass famine. By now millions were supposed to be perishing from hunger every year. It was the old doom-and-gloom mathematics of Thomas Malthus at work — population shoots up geometrically, while food production lags behind. It makes eminent sense. I grew up with Malthus’ ideas brought up-to-date in apocalyptic books like The Population Bomb.

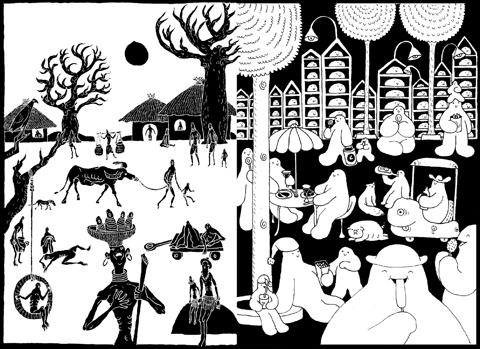

Someone, however, appears to have defused the bomb. Instead of mass starvation, we seem to be awash in food and it’s not just the US. Obesity is on the increase in Mexico. Fat-related diabetes is becoming epidemic in India. One in four people in China is overweight, more than 60 million are obese, and the rate of overweight children has increased almost 30-fold since 1985. Everywhere you look, from Buffalo to Beijing, you can see ballooning bellies.

Instead of going hungry, humans around the world on a per capita basis are eating more calories than ever before.

If you’re looking for reasons behind today’s obesity epidemic, don’t stop with the usual suspects, all of which are being trotted out by the press — fast food, trans fat, high sugar, low exercise, computer games, strange bacteria in your gut and weird molecules in your blood. I personally blame some hardwired human instinct for sitting around eating salty, greasy, sugary snacks in preference to hard physical labor. All of these factors are certainly related to the “insidious, creeping pandemic of obesity ... now engulfing the entire world,” as one gung-ho expert recently put it, but they are only bits of the puzzle.

The underlying answer is this — there’s a lot of cheap food around. Yes, walk into your local mega-grocery emporium or just about any food-selling area anywhere in the world and stare the problem in the face. There’s inexpensive, high-calorie food piled up all over the place.

Somehow we outsmarted Malthus. Food production has not only kept up with population growth, but has managed somehow to outstrip it. There are ups and downs from year to year because of the weather, and there are pockets of starvation around the world (not because of a global lack of food, but a lack of ways to transport it to where it’s needed). In general, silos are bursting.

Tonnes of food gets plowed under the ground because there’s so much of it farmers can’t get the prices they want. Tonnes of cheap food (corn, for instance) is used to create more expensive food (like steak). Lots of food means lots of grease, meat, sugar and calories. Lots of food means lots of overweight people.

If you like the idea of avoiding mass starvation — and I certainly do — you owe thanks to two groups of scientists. One group gave us the Green Revolution back around the 1980s via strains of hardy, high-yielding grains. The other figured out how to make bread out of air.

You heard me right. If you’re looking for someone to blame for today’s era of plenty, look to a couple of German scientists who lived a century ago. They understood that the problem was not a lack of food per se, but a lack of fertilizer — then they figured out how to make endless amounts of fertilizer.

The No. 1 component of any fertilizer is nitrogen, and the first of the two German researchers, Fritz Haber, discovered how to work the dangerous, complex chemistry needed to pull nitrogen out of the atmosphere — where it is abundant, but useless for fertilizer — and turn it into a substance that can grow plants.

A first demonstration was made 100 years ago. Carl Bosch, a young genius working for a chemical company, quickly ramped up Haber’s process to industrial levels. They both won Nobel Prizes.

It ranks among the great ironies of history that these two brilliant men, credited with saving millions from starvation, are also infamous for other work done later — Haber, a German Jew, was a central force in developing poison gas in World War I (and also performed research that led to the Zyklon B poison gas later used in concentration camps). Bosch, an ardent anti-Nazi, founded the giant chemical company I.G. Farben, which Hitler took over and used to make supplies for World War II.

Today, jaw-droppingly huge Haber-Bosch plants, much refined and improved, are humming around the world, pumping out the hundreds of thousands of tonnes of fertilizers that enrich the fields that grow the crops that become the sugars and oils and cattle that are cooked into the noodles, chips, pizza, burritos and snack cakes that make us fat.

If you don’t think this work important, consider that half the nitrogen in your body is synthetic, a product of a Haber-Bosch factory, or that without the added food made possible by their discovery, the earth could only support about 4 billion people — at least 2 billion less than today.

Yes, before you e-mail me, I understand the concomitant problems — stress on ecosystems, pollution (including nitrogen pollution), etc, but I am an optimist, so instead of moaning I will leave you with some more good news. Even with a world population that continues to add tens of millions of new mouths every year, given continuing growth in Haber-Bosch fertilizer and a surprising trend toward a worldwide decline in birth rates (if you live about 50 years longer, according to the best estimates, you’ll see humanity reach zero population growth), it might be within humanity’s grasp to avoid mass starvation forever.

Thomas Hager is author of The Alchemy of Air, a history of the Haber-Bosch discovery.

COPYRIGHT: PROJECT SYNDICATE

Taiwan aims to elevate its strategic position in supply chains by becoming an artificial intelligence (AI) hub for Nvidia Corp, providing everything from advanced chips and components to servers, in an attempt to edge out its closest rival in the region, South Korea. Taiwan’s importance in the AI ecosystem was clearly reflected in three major announcements Nvidia made during this year’s Computex trade show in Taipei. First, the US company’s number of partners in Taiwan would surge to 122 this year, from 34 last year, according to a slide shown during CEO Jensen Huang’s (黃仁勳) keynote speech on Monday last week.

When China passed its “Anti-Secession” Law in 2005, much of the democratic world saw it as yet another sign of Beijing’s authoritarianism, its contempt for international law and its aggressive posture toward Taiwan. Rightly so — on the surface. However, this move, often dismissed as a uniquely Chinese form of legal intimidation, echoes a legal and historical precedent rooted not in authoritarian tradition, but in US constitutional history. The Chinese “Anti-Secession” Law, a domestic statute threatening the use of force should Taiwan formally declare independence, is widely interpreted as an emblem of the Chinese Communist Party’s disregard for international norms. Critics

Birth, aging, illness and death are inevitable parts of the human experience. Yet, living well does not necessarily mean dying well. For those who have a chronic illness or cancer, or are bedridden due to significant injuries or disabilities, the remainder of life can be a torment for themselves and a hardship for their caregivers. Even if they wish to end their life with dignity, they are not allowed to do so. Bih Liu-ing (畢柳鶯), former superintendent of Chung Shan Medical University Hospital, introduced the practice of Voluntary Stopping of Eating and Drinking as an alternative to assisted dying, which remains

On May 7, 1971, Henry Kissinger planned his first, ultra-secret mission to China and pondered whether it would be better to meet his Chinese interlocutors “in Pakistan where the Pakistanis would tape the meeting — or in China where the Chinese would do the taping.” After a flicker of thought, he decided to have the Chinese do all the tape recording, translating and transcribing. Fortuitously, historians have several thousand pages of verbatim texts of Dr. Kissinger’s negotiations with his Chinese counterparts. Paradoxically, behind the scenes, Chinese stenographers prepared verbatim English language typescripts faster than they could translate and type them