Labrang, a Tibetan Buddhist monastery famed for its sacred scriptures and paintings, was nearly deserted over the May Day holiday.

A few pilgrims in traditional robes turned prayer wheels. Several young monks kicked a soccer ball on a dirt field.

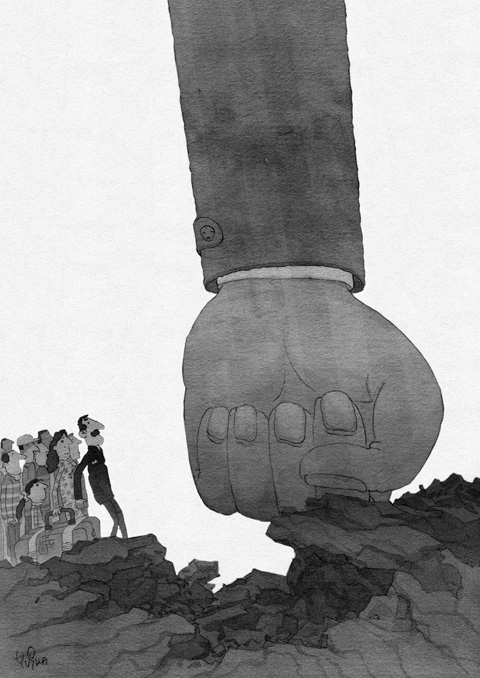

Tourism, an economic lifeline for many in this chronically poor region, has plunged since Tibetan protest against Chinese rule flared across a broad swath of western China in March, prompting Beijing to flood the area with troops. Foreigners are still banned, and until recently Chinese were advised to stay away.

In years past, busloads of tourists descended on the town of Xiahe in Gansu Province, with its 18th-century Labrang monastery. A billboard proclaims the area an “AAAA grade scenic tourist spot.” The number of visitors has plummeted more than 80 percent from last year’s 10,000, said Huang Qiangting with the Xiahe Tourism Bureau.

“It’s because of the incidents in March,” said Yuan Xixia, manager of the Labrang Hotel, whose 124 rooms were mostly vacant during last week’s May Day holiday. “I haven’t seen a tour bus on the street for days.”

In mid-March, two days of protests in Xiahe turned violent, with demonstrators smashing windows in government buildings, burning Chinese flags and displaying the banned Tibetan flag. It remains unclear how many people were killed or injured. Residents said some Tibetans died, while the Chinese media reported only injuries to 94 people in both Xiahe and surrounding towns in March, mostly police or troops.

Some expect business to remain slow until after the Beijing Olympic Games in August, when travel restrictions may be further eased. The streets were quiet on Thursday after the Olympic torch reached the top of Mount Everest, a peak considered sacred by Tibetans.

A shortening of the May Day break this year to three days from seven contributed to the drop in tourism. But most industry executives said the riots and tense security were the primary culprits.

The affected area includes not only Tibet but also the nearby provinces of Gansu, Qinghai and Sichuan, which have had sizable Tibetan communities for centuries.

South of Xiahe, five counties remain sealed off in Sichuan, where protests bubbled up anew last month, part of the most widespread demonstrations against Chinese rule since the Dalai Lama fled abroad nearly a half-century ago.

Nearby areas that are open, such as Jiuzhaigou, a picturesque valley of lakes and waterfalls surrounded by mountains, are seeing fewer visitors, travel agents said.

“This used to be the hottest season for tourists,” said a woman working at the Forest Hotel in Sichuan’s Aba County, the site of most of the unrest. She gave only her surname, Xie.

“But we haven’t seen any tour groups since March,” she said.

Meanwhile in Tibet’s capital of Lhasa, where Chinese authorities say 22 people died in violent riots in mid-March, hotels are almost empty at what should be the start of the busy tourist season.

At the Lhasa Hotel, only half of the 400 rooms were filled, said a staff member, Zhuoma, reached by telephone. Like many Tibetans, she uses one name.

The falloff in business is a blow to a ruggedly exotic but poor region where the government has encouraged tourism to provide a much-needed boost.

A tourism boom was underway in Tibet, generating new demand for guides, hotels and other services. Tibet had 4 million visitors last year, up 60 percent from 2006, the Xinhua news agency said, boosted by a new high-speed railway to Lhasa. Tourism revenues hit 4.8 billion yuan (US$687 million), more than 14 percent of the economy.

Beijing is eager for the area to regain its popularity. State media have run numerous cheerful pieces on life returning to normal.

“A trickle of Chinese tourists began arriving in ethnic Tibetan areas of west China over the May Day holiday, sparking hopes of a revival in the tourism industry after the unrest in March,” read one report by Xinhua.

“Lhasa seems busier and livelier than what I imagined,” tourist Wang Fujun from Chengdu was quoted as saying on Xinhua as he snapped photos outside the Potala Palace.

But that impression seemed an exaggeration in Xiahe.

“Since what happened in March, no one dares to come here anymore,” said a roadside fruit and vegetable vendor, who, like many refused to give his name for fear of retaliation from authorities.

“At this time of the year, the streets, hotels are all usually full. I normally sell all my produce in one day,” the vendor said, pointing to strawberries and watermelons piled next to leeks and lettuces. “Now, it takes me three days to sell the same amount.” Shopkeepers sit listlessly behind glass counters or in front of their stores, chatting with neighbors. Tibetan coin-studded leather belts, popular with Japanese tourists, hang unsold in a tiny store.

Eateries offer only limited menus, the lack of customers discouraging owners from buying food.

“Last year, this place was full everyday. Tourists from all over China, as well as France, Germany, England,” said the owner of a 50-seat cafe serving a local specialty of beef fried rice along with Western-style chicken burgers and french fries. “This year? Nobody.”

Wherever one looks, the United States is ceding ground to China. From foreign aid to foreign trade, and from reorganizations to organizational guidance, the Trump administration has embarked on a stunning effort to hobble itself in grappling with what his own secretary of state calls “the most potent and dangerous near-peer adversary this nation has ever confronted.” The problems start at the Department of State. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has asserted that “it’s not normal for the world to simply have a unipolar power” and that the world has returned to multipolarity, with “multi-great powers in different parts of the

President William Lai (賴清德) recently attended an event in Taipei marking the end of World War II in Europe, emphasizing in his speech: “Using force to invade another country is an unjust act and will ultimately fail.” In just a few words, he captured the core values of the postwar international order and reminded us again: History is not just for reflection, but serves as a warning for the present. From a broad historical perspective, his statement carries weight. For centuries, international relations operated under the law of the jungle — where the strong dominated and the weak were constrained. That

The Executive Yuan recently revised a page of its Web site on ethnic groups in Taiwan, replacing the term “Han” (漢族) with “the rest of the population.” The page, which was updated on March 24, describes the composition of Taiwan’s registered households as indigenous (2.5 percent), foreign origin (1.2 percent) and the rest of the population (96.2 percent). The change was picked up by a social media user and amplified by local media, sparking heated discussion over the weekend. The pan-blue and pro-China camp called it a politically motivated desinicization attempt to obscure the Han Chinese ethnicity of most Taiwanese.

The Legislative Yuan passed an amendment on Friday last week to add four national holidays and make Workers’ Day a national holiday for all sectors — a move referred to as “four plus one.” The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), who used their combined legislative majority to push the bill through its third reading, claim the holidays were chosen based on their inherent significance and social relevance. However, in passing the amendment, they have stuck to the traditional mindset of taking a holiday just for the sake of it, failing to make good use of