It is only when Shoko Tendo removes her tracksuit top that you appreciate why, even on a hot day, she prefers to remain covered up in public. Outwardly she is much like any 30-something you would be likely to encounter on a Tokyo street.

Her hair is of the dark-brown hue favored by many Japanese women her age, her greeting is accompanied by a well-executed bow and her voice seems to be pitched a little on the high side, a common affectation in the company of strangers.

But her protective layer comes off to reveal stick-thin arms covered, from the wrists up, with a tattoo that winds its way to her chest and across her back, culminating, on her left shoulder, in the face of a Muromachi-era courtesan with breast exposed and a knife clenched between her teeth.

It is an appropriately defiant image for Tendo and the most obvious sign that, as the daughter of a yakuza boss, she hails from a section of Japanese society that most of her compatriots would rather did not exist.

Her story, Yakuza Moon: Memoirs of a Gangster's Daughter, which was published in the UK in May, became a surprise bestseller in Japan in 2004, shining a light into a dark and little understood corner of modern Japan. With the release of the English version, her story of a happy early childhood that then quickly descended into delinquency, addiction and a string of abusive relationships is set to reach a much wider audience.

"I hated the way my father behaved," she said at the Tokyo office of her publisher, Kodansha International. "But then I became just like him. I was a glue-addicted delinquent [her misdemeanors earned her an eight-month stay in a reformatory]. I behaved exactly like a junior yakuza, picking fights and not caring about how other people felt."

After years of relative calm, the yakuza have recently captured the public imagination in Japan. The swearing-in two summers ago of a new godfather of Japan's biggest underworld organization, the Yamaguchi-gumi, was followed by a spate of shootings of high-level gangland bosses, and then, in April this year, the assassination, also by shooting, of progressive Nagasaki mayor Itcho Ito.

But though much has been written about the male members of the yakuza fraternity -- the drink, the money, the women and the violence -- much less is known about the ones closest to them in their lives -- their wives, daughters and lovers. Tendo has been all three.

Her status as the daughter of a gangland boss was the cause of her troubled youth, a history involving being bullied at school to dealing with the expectation of drug-fueled sex among men to whom her father was somehow indebted. As a teenager she was repeatedly raped by men who fed her addiction to drugs then left her bloody and bruised in seedy hotel rooms.

Only her make-up hides the scars from the reconstructive surgery she required on her face after a particularly bad beating. Her marriage to someone with gangster ties ended quickly, although she still talks of him as a "serious, well-intentioned" man who treated her well.

Tendo's last speed fix came when she was 19, when her injuries from another beating in the room of a motel came close to killing her.

"I kept thinking, `I don't want to die in a place like this.' I was there for an hour and managed to drag myself home ... I knew it was time to stop," she said.

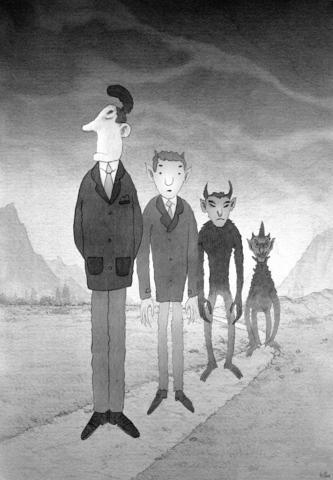

tattoo

She quickly rose up the ranks of the Tokyo hostess scene, but it was her decision, in her early 20s, to tattoo the top half of her body, yakuza-style, that marked the end of her emotional and physical dependence on the men of violence.

It also marked the beginning of the new life she has since made as a writer and, now, as a mother.

The popular image of yakuza families as ostentatiously wealthy and loyal to the core bears little resemblance to Tendo's early experiences of poverty and betrayal.

She has a hatred of gangsters that is partly due to the shabby way in which her father's associates treated him in his hour of need.

"They gave him `sympathy' money to tide him over after his business failed and he became ill, but they basically left him to sink on his own," she said. "Only his really good friends ever visited him in hospital."

When we met she was furiously trying to meet the final deadline for her second book, which she said would be a more light-hearted look at life as a single mother.

She was reluctant to talk about the father of her 18-month-old daughter, saying only that he was a photographer with whom she remained on friendly terms.

She does not believe she is the only one among yakuza offspring who endured a turbulent childhood.

"Japanese society looks very calm on the surface, but underneath it is in turmoil," she said. "Discrimination is rife."

Though she is not ashamed of her tattoo, she knows even a tiny patch of the tell-tale ink poking out from underneath the cuffs of her shirt is enough to invite looks of disgust.

"Musicians and artists can get away with showing off their tattoos, but a delinquent like me does her best to hide them," she said.

Despite the satisfaction she gets from writing, she says her struggle for acceptance in a deeply conservative society goes on.

"There is a big difference between becoming a single mother after a divorce and because you choose to be one," she said.

But she is adamant that she would not change her past.

"I had a hard time as the daughter of a gangster, but looking back I wouldn't have lived my life any other way. I am proud that my father was a yakuza. I know his is a world that has no proper place for women. But I have his DNA," she said.

There is a modern roadway stretching from central Hargeisa, the capital of Somaliland in the Horn of Africa, to the partially recognized state’s Egal International Airport. Emblazoned on a gold plaque marking the road’s inauguration in July last year, just below the flags of Somaliland and the Republic of China (ROC), is the road’s official name: “Taiwan Avenue.” The first phase of construction of the upgraded road, with new sidewalks and a modern drainage system to reduce flooding, was 70 percent funded by Taipei, which contributed US$1.85 million. That is a relatively modest sum for the effect on international perception, and

At the end of last year, a diplomatic development with consequences reaching well beyond the regional level emerged. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu declared Israel’s recognition of Somaliland as a sovereign state, paving the way for political, economic and strategic cooperation with the African nation. The diplomatic breakthrough yields, above all, substantial and tangible benefits for the two countries, enhancing Somaliland’s international posture, with a state prepared to champion its bid for broader legitimacy. With Israel’s support, Somaliland might also benefit from the expertise of Israeli companies in fields such as mineral exploration and water management, as underscored by Israeli Minister of

When former president Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文) first took office in 2016, she set ambitious goals for remaking the energy mix in Taiwan. At the core of this effort was a significant expansion of the percentage of renewable energy generated to keep pace with growing domestic and global demands to reduce emissions. This effort met with broad bipartisan support as all three major parties placed expanding renewable energy at the center of their energy platforms. However, over the past several years partisanship has become a major headwind in realizing a set of energy goals that all three parties profess to want. Tsai

Chile has elected a new government that has the opportunity to take a fresh look at some key aspects of foreign economic policy, mainly a greater focus on Asia, including Taiwan. Still, in the great scheme of things, Chile is a small nation in Latin America, compared with giants such as Brazil and Mexico, or other major markets such as Colombia and Argentina. So why should Taiwan pay much attention to the new administration? Because the victory of Chilean president-elect Jose Antonio Kast, a right-of-center politician, can be seen as confirming that the continent is undergoing one of its periodic political shifts,