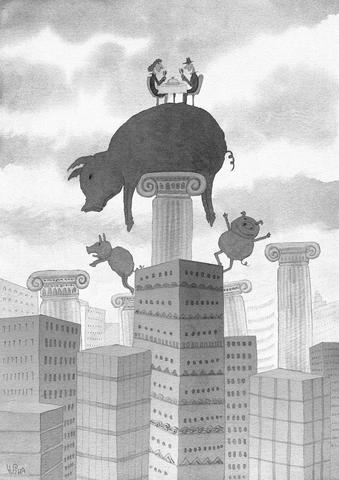

Few things are as essential to the Chinese as their pigs.

From spare ribs to barbecued pork buns, pork is a staple of the Chinese diet. So, in this Year of the Pig, an acute shortage of pork has been national news as butchers raise prices almost daily and politicians scramble to respond.

Steep increases for pork loins and bacon are the most tangible sign that, after a decade in which prices have fluctuated but not moved significantly upward, inflation is creeping back into China. In response to this pressure at home, Chinese companies are starting to raise prices for exports, removing what has been a brake on inflation in the West.

With the global economy expanding at a robust pace, prices are rising in fast-developing countries like India and Mexico and central bankers and investors are becoming concerned. Interest rates are inching up in the US and Europe as lenders demand that borrowers pay more to offset the erosion of buying power over time.

Business executives say that with wages rising 10 percent or more a year in many Chinese cities, the country's days are numbered as the world's lowest-cost producer of many cheap labor-intensive products, like toys and shoes.

"People tend to underestimate the deflationary impact over the last 10 years" from Chinese exports, said Michael Smith, the chief executive of HSBC's Asian operations. "It has got to the limit: You've had wage inflation, you've got rising natural resource prices, there's just no more give."

The crisis over pork prices in China, like the jolt many Americans feel when gasoline prices jump, offers one example of how prices can suddenly soar. The Chinese government is struggling to cope -- including deliberations over whether to sell a snuffling, smelly strategic reserve of hun-dreds of thousands of live pigs kept at special subsidized farms for precisely the shortage the country is now facing.

Chinese officials offer several reasons for high pig prices. The cost of animal feed has risen by one-quarter in the last year, partly because more corn is being made into ethanol and partly because more prosperous workers are eating more meat, which requires more animal feed.

The cost of pig veterinary medicine has increased, too. Some pig farms that shut down because of low prices last year were unprepared for strong demand this spring. And outbreaks of disease have killed many pigs, though no reliable estimates of how many are available.

The most recent statistics from the agriculture ministry show that prices for live pigs rose 71.3 percent in April from March, while pork prices climbed 29.3 percent, to the dismay of shoppers.

Some consumers were irritated with pork prices on two recent afternoons at a busy street market in metropolitan Guangzhou. A woman walked up to Zhang Hanbiao, a butcher standing behind an unrefrigerated counter of raw pork under the glare of two large light bulbs, and asked him the price of the dark red slab of pig liver.

Told the answer -- 7.5 yuan a catty, or US$2.50 a kilo, up about 20 percent from last time -- she stalked off in silence without making a purchase.

Her response angered Zhang, a butcher with a faint mustache who has followed a Chinese tradition of letting his nails grow long on the little fingers of each hand.

"No business!" he exclaimed. "I've lost 1,000 yuan in three days because the meat goes bad before I can sell it."

Another woman came to the counter, sniffed some pork suspiciously, but then kept right on walking.

"After it turns color, people won't buy it," Zhang said, adding that roadside snack vendors buy unsold meat at a discount each evening.

Wu Lijuan, a Guangzhou resident who bought a small plastic bag of lean pork from Zhang, said she was eating less pork and more fish as pork prices rise. But prices for chicken, beef, fish and eggs are also rising sharply this spring, along with the cost of animal and fish feed, although not quite as fast as pork.

In a move to head off possible protests among sometimes volatile students, the education ministry has ordered colleges and universities to subsidize pork instead of raising prices on campus. The civil affairs ministry has instructed municipal governments to subsidize pork purchases by low-income families, while the railway ministry has given priority to pig shipments.

Premier Wen Jiabao (溫家寶) visited the pork counter at a supermarket in Xian, Shaanxi Province, on May 26 and called for local governments to pay pig farmers to increase production. The commerce ministry has raised the possibility of distributing pork from China's strategic pork reserves.

State-controlled television in Shandong Province ran a detailed report late last month on the reserves. The commerce ministry keeps a national reserve of frozen pork and live pigs and local governments keep their own reserves as well, constantly selling older supplies and procuring fresh stock. Government agencies pay a pig subsidy to farmers to keep their animals in the program.

"The sties are very roomy, there is heat in the winter and fans in the summer," the television program said, describing conditions very different from those endured by many pigs in China, including those here in Gaoyao, 80km west of Guangzhou.

Yang Yuanji stood in sweltering heat next to his fetid, crudely built pigpens on a recent afternoon and contended that he needed high prices to pay for costly animal feed and medicine.

"Everyone says pork prices are high -- I don't think so," he said.

One of his neighbors, Yang Ming, said he did not believe that farmers were withholding pigs from the market -- as the state media occasionally hint -- in the hope that prices will keep rising.

"I don't wait, I sell a pig as soon as it reaches 180 catties [90.72 kg]," he said.

Pork has been a cornerstone of the Chinese diet for centuries. Rows of 2,100-year-old terra cotta pigs were recently discovered near Xian, a city better known for terra cotta warriors. China's 1.3 billion people eat more than 42 billion kilograms of pork a year -- 90g a day for every man, woman and child in the country.

And just as higher gasoline prices can lead to a political reaction in the US, the Chinese government is particularly worried about swiftly increasing pork prices because of their impact on household budgets and the way they can exacerbate income inequality.

Pork is a critical source of protein for Chinese of all incomes, but particularly for low-income workers like those who keep American and European families well supplied with US$49 DVD players and other popular consumer products.

Broader measures of consumer prices showed inflation of only 3 percent in April, but Goldman Sachs is now predicting that the higher meat prices will be pushing this above 4 percent "very soon."

Heavy investments in new factories, roads, rail lines and ports have helped limit inflation until now in manufactured goods as productivity improvements mostly offset rising wages and higher prices for food, oil and metals.

Economists and business executives say that manufacturers face growing pressure to raise prices as well, particularly with the torrent of money pouring into China now, which has helped push up the prices of Chinese stocks and real estate.

But the price that many Chinese care about most these days is the price of pork. Not far from Zhang's butcher counter is a small shop selling unrefrigerated barbecue. Cherry Zhou, a shop worker, said the shop had raised prices 25 percent in the last few days.

Blaming pork distributors, she said: "It's more expensive by the week."

Wherever one looks, the United States is ceding ground to China. From foreign aid to foreign trade, and from reorganizations to organizational guidance, the Trump administration has embarked on a stunning effort to hobble itself in grappling with what his own secretary of state calls “the most potent and dangerous near-peer adversary this nation has ever confronted.” The problems start at the Department of State. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has asserted that “it’s not normal for the world to simply have a unipolar power” and that the world has returned to multipolarity, with “multi-great powers in different parts of the

President William Lai (賴清德) recently attended an event in Taipei marking the end of World War II in Europe, emphasizing in his speech: “Using force to invade another country is an unjust act and will ultimately fail.” In just a few words, he captured the core values of the postwar international order and reminded us again: History is not just for reflection, but serves as a warning for the present. From a broad historical perspective, his statement carries weight. For centuries, international relations operated under the law of the jungle — where the strong dominated and the weak were constrained. That

The Executive Yuan recently revised a page of its Web site on ethnic groups in Taiwan, replacing the term “Han” (漢族) with “the rest of the population.” The page, which was updated on March 24, describes the composition of Taiwan’s registered households as indigenous (2.5 percent), foreign origin (1.2 percent) and the rest of the population (96.2 percent). The change was picked up by a social media user and amplified by local media, sparking heated discussion over the weekend. The pan-blue and pro-China camp called it a politically motivated desinicization attempt to obscure the Han Chinese ethnicity of most Taiwanese.

The Legislative Yuan passed an amendment on Friday last week to add four national holidays and make Workers’ Day a national holiday for all sectors — a move referred to as “four plus one.” The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), who used their combined legislative majority to push the bill through its third reading, claim the holidays were chosen based on their inherent significance and social relevance. However, in passing the amendment, they have stuck to the traditional mindset of taking a holiday just for the sake of it, failing to make good use of