A midst all the headlines about the Democrats gaining control of the US Congress in last month's elections, one big election result was largely ignored. Although it illuminated the flaws of the US political system, it also restored my belief in the compassion of ordinary Americans.

In Arizona, citizens can, by gathering a sufficient number of signatures, put a proposed law to a direct popular vote. This year, one of the issues on the ballot was an act to prohibit tethering or confining a pregnant pig, or a calf raised for veal, in a manner that prevents the animal from turning around freely, lying down, and fully extending his or her limbs.

Those who know little about modern factory farming may wonder why such legislation would be necessary. Under farming methods that were universal 50 years ago, and that are still common in some countries today, all animals have the space to turn around and stretch their limbs.

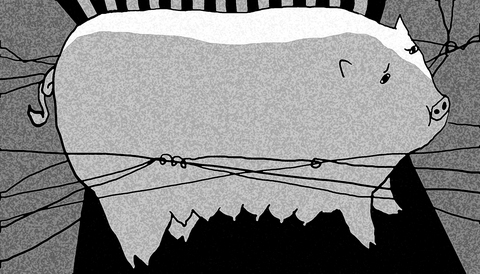

Today, however, about 90 percent of US breeding sows -- the mothers of the pigs that are raised and killed for pork, bacon, and ham -- spend most of their lives locked in cages that measure about 0.6m by 2.2m. They are unable to turn around, lie down with their legs fully extended, or move more than a step forward or backward. Other sows are kept on short tethers that also prevent them turning around. Veal calves are similarly confined for all their lives in individual stalls that do not permit them to turn around, lie down or stretch their limbs. These methods are, essentially, labor-saving devices -- they make management of the animals easier and enable units with thousands or tens of thousands of animals to employ fewer and less skilled workers. They also prevent the animals from wasting energy by moving around or fighting with each other.

Several years ago, following protests from animal welfare organizations, the EU commissioned a report from its Scientific Veterinary Committee on these methods. The committee found that animals suffer from being unable to move freely and from the total lack of anything to do all day. Common sense would, of course, have reached the same conclusion.

Following the report, the EU set dates by which close confinement of these animals would be prohibited. For veal calves, that date, Jan. 1, next year, is almost here. Individual stalls for sows, already outlawed in the UK and Sweden, will be banned across the entire EU from 2013. Measures to improve the welfare of laying hens, which are typically kept crammed into bare wire cages with no room to stretch their wings, are also being phased in.

In the US, no such national measures are anywhere in sight. In the past, when my European friends have asked me why the US lags so far behind Europe in matters of animal welfare, I have had no answer. When they pressed me, I had to admit that the explanation could be that Americans care less about animals than Europeans.

Then, in 2002, animal welfare advocates put a proposal to ban sow stalls on the ballot in Florida. To the surprise of many, it gained the approval of 55 percent of those voting. Last month in Arizona, despite well-funded opposition from agribusiness, the ban on small cages for sows and veal calves also passed, with 62 percent support.

Neither Florida nor Arizona are particularly progressive states -- both voted for US President George W. Bush over Senator John Kerry in 2004. So the results strongly suggest that if all Americans were given a chance to vote on keeping pregnant pigs and calves in such tight confinement, the majority would vote no. Americans seem to care just as much about animal welfare as Europeans do.

So, to explain the gap between Europe and the US on farm animal welfare, we should look to the political system. In Europe, the concerns of voters about animal welfare have been effective in influencing members of national parliaments, as well as members of the EU Parliament, resulting in national laws and EU directives that respond to those concerns.

In the US, by contrast, similar concerns have had no discernible effect on members of Congress. There is no federal legislation at all on the welfare of farm animals -- and very little state legislation, either. That, I believe, is because agribusiness is able to put millions of dollars into the pockets of congressional representatives seeking re-election. The animal welfare movement, despite its broad public support, has been unable to compete in the arena of political lobbying and campaign donations.

In US electoral politics, money counts for more than the opinions of voters. Party discipline is weak, and members of Congress must themselves raise most of the money that they need for re-election -- and that happens every two years for members of the House of Representatives. In Europe, where party discipline is strong and the parties, not individuals, finance election campaigns, money plays a smaller role. In the US, a nation that prides itself on its democratic traditions, pigs and calves are hardly the only losers.

Peter Singer is professor of bioethics at Princeton University and the co-author of The Way We Eat: Why Our Food Choices Matter. Copyright: Project Syndicate

Wherever one looks, the United States is ceding ground to China. From foreign aid to foreign trade, and from reorganizations to organizational guidance, the Trump administration has embarked on a stunning effort to hobble itself in grappling with what his own secretary of state calls “the most potent and dangerous near-peer adversary this nation has ever confronted.” The problems start at the Department of State. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has asserted that “it’s not normal for the world to simply have a unipolar power” and that the world has returned to multipolarity, with “multi-great powers in different parts of the

President William Lai (賴清德) recently attended an event in Taipei marking the end of World War II in Europe, emphasizing in his speech: “Using force to invade another country is an unjust act and will ultimately fail.” In just a few words, he captured the core values of the postwar international order and reminded us again: History is not just for reflection, but serves as a warning for the present. From a broad historical perspective, his statement carries weight. For centuries, international relations operated under the law of the jungle — where the strong dominated and the weak were constrained. That

The Executive Yuan recently revised a page of its Web site on ethnic groups in Taiwan, replacing the term “Han” (漢族) with “the rest of the population.” The page, which was updated on March 24, describes the composition of Taiwan’s registered households as indigenous (2.5 percent), foreign origin (1.2 percent) and the rest of the population (96.2 percent). The change was picked up by a social media user and amplified by local media, sparking heated discussion over the weekend. The pan-blue and pro-China camp called it a politically motivated desinicization attempt to obscure the Han Chinese ethnicity of most Taiwanese.

The Legislative Yuan passed an amendment on Friday last week to add four national holidays and make Workers’ Day a national holiday for all sectors — a move referred to as “four plus one.” The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), who used their combined legislative majority to push the bill through its third reading, claim the holidays were chosen based on their inherent significance and social relevance. However, in passing the amendment, they have stuck to the traditional mindset of taking a holiday just for the sake of it, failing to make good use of