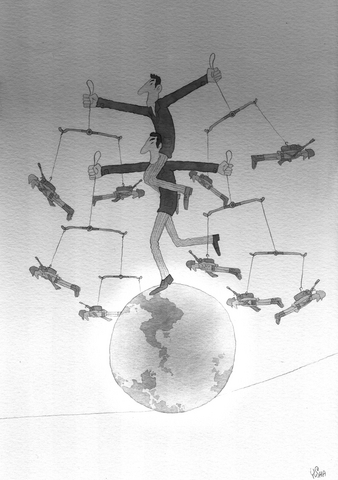

Listen carefully these days to Israelis and South Koreans. What they are hinting at is no less than a tectonic shift in the international system -- the shift from a unipolar to a multipolar world.

Israelis are rediscovering Europe. They intuitively sense that they can no longer rely only on the absolute security guarantee represented by the combination of active and passive support of the US. The war in Lebanon, so frustrating for Israel, accelerated that subtle change. Now Europe and its various contingents are playing a leading role in picking up the pieces there.

The US, of course, remains Israel's life insurance policy, but enlargement and diversification of diplomatic alliances is starting to be seen as crucial by Israeli diplomats, if not by Israeli society.

The Quartet (the US, Russia, the EU and the UN) used to be regarded as "One plus Three," but that is no longer the case. Europe and Russia no longer see themselves as secondary players, because the US, not to mention Israel, needs them.

As for the South Koreans, they are counting on China to deal with the North Korean nuclear crisis. They, too, see the world through a prism that makes the US continue to appear essential, but no longer preeminent.

Recently, a high South Korean official listed in hierarchical order the countries that mattered most in the North Korean nuclear crisis. China came first, followed by the US, Russia, Japan, and South Korea, whereas Europe was absent.

These are only a few signs among many others. One could also mention the recent Sino-African summit in Beijing, or the intensification of Venezuelan-Iranian relations. All these developments subtly indicate a deep trend that can be formalized in one sentence -- The unipolar moment of the US, which began in 1991 with the collapse of the Soviet Empire, is over.

Of course, one should not "bury" the US too soon. The US is much more resilient than its critics believe. It has a unique capacity to rebound, and it controls unparalleled military, intellectual, economic, and even political resources.

The Republicans' defeat in this month's mid-term Congressional elections is a sign that Americans want to sanction their leaders for their strategic and ethical shortcomings, and they did so with gusto.

But this resilience should not hide a deeper evolution. The US is no longer alone. It no longer qualifies, if it ever did, as a "hyper power," to use former French foreign minister Hubert Vedrine's term, though it is still far from being a "normal" power.

The inadvertent "passivity" of the US in the Clinton years and the wrong directions of the Bush years coincided with the rise of China and India, as well as Russia's renewed international clout as a result of high oil prices.

These developments ushered in the slow, imperfect return of an unbalanced multi-polar system. The world in which we live may be moving toward the multi-polarity wished for by French President Jacques Chirac, but not necessarily in a successful and stable way.

If, contrary to the traditional "Gaullist" vision, multi-polarity is not bringing stability, but instead generating chaos, there are two reasons for this outcome.

First, key emerging actors -- China, Russia, and India -- are not ready, willing, or even capable of performing a stabilizing international role. They are either too cynical or timid in their vision of the world, or they have others priorities, or both.

They probably contemplate with barely disguised pleasure the difficulties currently encountered by the US in Iraq and elsewhere, but they do not feel any sense of a "compensating responsibility" for global stability. The common good is not their cup of tea. They have too much to catch up with, in terms of national ego and national interest, to care for others.

Second, the EU is the only natural US ally in terms of values. It is the EU that can make multi-polarity work if it plays its role positively.

If the EU appears more concerned with the best ways to avoid the responsibilities that may befall it as a result of the new and enforced modesty of the US, then multi-polarity will result -- by default, not by design -- in a more chaotic world, rather than leading to greater stability.

Europe has a unique chance to demonstrate that it can make a difference in the post-unipolar moment of the US. It starts right now in the Middle East.

The world that Europe has called for is coming closer, and it can fail abysmally without the EU or improve at the margin thanks to it.

In some ways, the end of a unipolar world could truly be the "Hour of Europe." But that can happen only if the EU regains its confidence and steps into a positive role -- one that it must play with, not against, the US.

Dominique Moisi, a founder and senior advisor at IFRI (French Institute for International Relations), is a professor at the College of Europe in Natolin, Warsaw.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

President William Lai (賴清德) attended a dinner held by the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) when representatives from the group visited Taiwan in October. In a speech at the event, Lai highlighted similarities in the geopolitical challenges faced by Israel and Taiwan, saying that the two countries “stand on the front line against authoritarianism.” Lai noted how Taiwan had “immediately condemned” the Oct. 7, 2023, attack on Israel by Hamas and had provided humanitarian aid. Lai was heavily criticized from some quarters for standing with AIPAC and Israel. On Nov. 4, the Taipei Times published an opinion article (“Speak out on the

More than a week after Hondurans voted, the country still does not know who will be its next president. The Honduran National Electoral Council has not declared a winner, and the transmission of results has experienced repeated malfunctions that interrupted updates for almost 24 hours at times. The delay has become the second-longest post-electoral silence since the election of former Honduran president Juan Orlando Hernandez of the National Party in 2017, which was tainted by accusations of fraud. Once again, this has raised concerns among observers, civil society groups and the international community. The preliminary results remain close, but both

News about expanding security cooperation between Israel and Taiwan, including the visits of Deputy Minister of National Defense Po Horng-huei (柏鴻輝) in September and Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Francois Wu (吳志中) this month, as well as growing ties in areas such as missile defense and cybersecurity, should not be viewed as isolated events. The emphasis on missile defense, including Taiwan’s newly introduced T-Dome project, is simply the most visible sign of a deeper trend that has been taking shape quietly over the past two to three years. Taipei is seeking to expand security and defense cooperation with Israel, something officials

The Taipei Women’s Rescue Foundation has demanded an apology from China Central Television (CCTV), accusing the Chinese state broadcaster of using “deceptive editing” and distorting the intent of a recent documentary on “comfort women.” According to the foundation, the Ama Museum in Taipei granted CCTV limited permission to film on the condition that the footage be used solely for public education. Yet when the documentary aired, the museum was reportedly presented alongside commentary condemning Taiwan’s alleged “warmongering” and criticizing the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) government’s stance toward Japan. Instead of focusing on women’s rights or historical memory, the program appeared crafted