Fifteen years after female brokers sued Smith Barney & Co in a lawsuit famously known as the Boom-Boom Room case, financial firms have set up harassment training, torn racy photographs from the walls and pulled the plug on -company-paid outings to strip joints.

Despite all that, the industry is far from cured of a male--dominated culture where women can be intimidated and underpaid for work equal to the guys. And a recent US Supreme Court decision could block future progress by limiting female plaintiffs’ access to court and forcing more cases into closed-door arbitration.

After the arrest of former IMF chief Dominique Strauss-Kahn on sexual-assault charges, details are emerging about an IMF culture so intimidating to some women that they decline to wear skirts at the office.

Photo: AFP

Other examples are bubbling up worldwide. Last month, a German newspaper revealed that a subsidiary of Munich Re, the world’s biggest reinsurance company, had hired 20 prostitutes to entertain 100 top insurance agents in Budapest in 2007. The company said the event violated its policy.

And it’s not just the actions of high-flying IMF chiefs or European insurers at issue. Such behavior exists in the far corners of Wall Street, as seen in the recent case of a former sales assistant at UBS Financial Services in Kansas City, Missouri. On May 3, a jury awarded her US$10.5 million, including punitive damages, for sexual harassment and retaliation, after a 16-day trial that had more references to breasts and male sex organs than you’s find in a romance novel.

Several jurors sat at the edge of their seats as they heard how a broker and defendant in the case put on the desk of plaintiff Carla Ingraham an article entitled “The vibrator: What’s all the buzz about?”

Photo: AFP

After the verdict, the firm said in a statement that it will “ensure to the best of our ability that this kind of conduct does not occur again,” and that it does not tolerate harassment of any kind.

UBS hasn’t decided whether to appeal, said a spokeswoman for the bank, Karina Byrne.

“Wall Street is the king of harassment,” says Greg-Patric Martello, who represented two women who sued a Uniondale, New York, brokerage firm for harassment and won US$1.1 million in an arbitration case last month at the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority. “I’ve never seen an industry like it.”

Every industry has its problems with discrimination. The US securities business, though, has been particularly slow to improve, in part the legacy of a system that shielded it almost entirely from the courts until 1999. That year, the Securities and Exchange Commission changed the rule that had forced discrimination claims by licensed securities employees to be heard by private, industry-run arbitration panels.

Today, many securities firms prevent employees from airing their complaints in court by requiring them to sign contracts obliging them to use arbitration. Women who are bound by such agreements are able to get into court only if a judge determines that they represent a class.

High-profile cases like the Smith Barney lawsuit had sneaked into court before 1999 through a loophole: Wall Street arbitration panels weren’t equipped to hear class-action cases, thus giving groups of women who joined in a class a back door into court.

That loophole is likely to close as a result of an April 27 Supreme Court decision in AT&T Mobility v Concepcion, in which the court said that AT&T could block a class-action suit and force customers into arbitration.

“We will see major growth in employment arbitration,” as a result of the AT&T case, says Alexander Colvin, a Cornell University associate professor of labor relations, whose research shows that employees fare worse in arbitration than they do in court.

The AT&T decision will make disclosures that come from suits like Ingraham’s even rarer.

Today, with Wall Street discrimination cases scattered among courts, private arbitration panels and dispute resolution groups, it’s impossible to say how many cases are filed, or how often women win. Even the very public Boom-Boom Room case ended with opacity. Most of the nearly 2,000 women involved signed confidentiality agreements before settling. The lead plaintiff, Pamela Martens, objected to the settlement terms and got nothing after losing her fight for a court hearing.

Douglas Wigdor, a New York lawyer representing six women in two cases against Citigroup Inc, estimates that 1 percent of complaints against Wall Street firms go to trial. That makes the Ingraham case an extraordinary window onto how Wall Street treats female employees.

One thing is certain, says Cliff Palefsky, a lawyer at McGuinn, Hillsman & Palefsky in San Francisco who has fought against mandatory arbitration for two decades: “You can have 20 secret plaintiffs’ awards in discrimination cases in securities arbitrations, and they won’t have one-10th of the real-world impact as the Ingraham verdict.”

As I wrote in my 2002 book, Tales from the Boom-Boom Room, Smith Barney’s office revelers met in a basement room to pump up the music on a boom box and mix garbage pails-full of Bloody Marys amid vulgarity and bravado. At UBS in Kansas City, the gang would gather after business hours for drinks and frivolity in a broker’s office dubbed “The Party Cove.” Halloween in 2007 was one such occasion and the group took delight that someone had purchased a package of fake mustaches. Ingraham’s lawyer said in court that a male broker donned one of the mustaches and began to simulate having sex with an imaginary partner, though others at the party testified that they never saw that.

In November 2007, the staff enjoyed an open bar paid for by UBS at a country club in Mission Hills, Kansas, and then filed into a banquet room. The post-cocktail agenda: A human resources manager was presenting “Respect in the Workplace,” the UBS seminar on discrimination and harassment.

Worst among the Kansas City drinking stories is the tale of the “naked auditors.” When the Weehawken, New Jersey, home office sent two examiners to review the books in 2008, they wound up socializing after hours with female staffers. According to court testimony, one auditor became so drunk that he vomited on himself in the parking lot, was driven back to his hotel and invited one of the women to join him in the shower after taking his clothes off. Several doors down, the other auditor asked the second woman if she would like to give him oral sex.

Both women declined the offers and relayed the events to a compliance officer, who testified that she took the matter no further because the women didn’t appear to have been offended.

A recurring defense by UBS was that Ingraham and other women participated in the drinking and banter. A broker, for example, sent Ingraham an e-mail with a video showing women baring their breasts; she sent him an e-mail about Cialis, the erectile dysfunction drug.

It’s not unusual for women working in a high-testosterone atmosphere to adapt by taking on behavior like that of the men they work with, says Charlotte Fishman, executive director of Pick Up the Pace, a research and advocacy organization for women in the workplace.

“Whenever you’re in a situation where it’s a boys’ club, there is pressure to be one of the boys,” she says.

Ingraham put it this way: “There is no denying I sent joke e-mails. I was immersed in that culture.”

After 22 years at her job and performance evaluations that consistently ranked her above average, Ingraham in 2008 complained about harassment to the UBS in-house dispute resolution program. Two UBS investigators looked into the complaints, but put a surprising amount of effort into searching for dirt on her. On July 1, 2009, UBS fired her. She had been videotaping some of her office colleagues and lied about it when management confronted her.

There is no arguing that UBS took some constructive actions after Ingraham’s complaints, including putting letters in violators’ personnel files and retraining Kansas City managers — with no happy hour beforehand.

John Ellspermann, then the most senior manager at the branch, got a letter of reprimand for having sent and received numerous “offensive and inappropriate” e-mails and a 5 percent cut in his bonus. Reached at Morgan Stanley, where he now works, Ellspermann declined to comment. It’s hard to imagine that any of that would have happened without the spotlight Ingraham put on the matter.

There are ways to fix these problems. Mandatory arbitration should be banned, allowing employees to choose between courts and arbitration. Public records of people with securities licenses should include specifics about all firings; today, substantial wiggle room allows brokers to say they’ve been “permitted to resign.”

When the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission or private plaintiffs negotiate settlements, they should demand five years of court monitoring to make sure future complaints are handled properly and promotions are doled out fairly. It takes that long for change to take hold, according to a study in March, Ending Sex and Race Discrimination in the Workplace, by the Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

A cultural change won’t happen by relying on the industry. UBS has “as stringent a policy on sex harassment as anyone in the industry,” Byrne says.

For that reason alone, it’s a no-brainer that only changes in public policy will make a difference.

In Italy’s storied gold-making hubs, jewelers are reworking their designs to trim gold content as they race to blunt the effect of record prices and appeal to shoppers watching their budgets. Gold prices hit a record high on Thursday, surging near US$5,600 an ounce, more than double a year ago as geopolitical concerns and jitters over trade pushed investors toward the safe-haven asset. The rally is putting undue pressure on small artisans as they face mounting demands from customers, including international brands, to produce cheaper items, from signature pieces to wedding rings, according to interviews with four independent jewelers in Italy’s main

Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi has talked up the benefits of a weaker yen in a campaign speech, adopting a tone at odds with her finance ministry, which has refused to rule out any options to counter excessive foreign exchange volatility. Takaichi later softened her stance, saying she did not have a preference for the yen’s direction. “People say the weak yen is bad right now, but for export industries, it’s a major opportunity,” Takaichi said on Saturday at a rally for Liberal Democratic Party candidate Daishiro Yamagiwa in Kanagawa Prefecture ahead of a snap election on Sunday. “Whether it’s selling food or

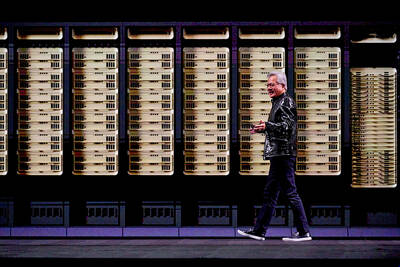

CONCERNS: Tech companies investing in AI businesses that purchase their products have raised questions among investors that they are artificially propping up demand Nvidia Corp chief executive officer Jensen Huang (黃仁勳) on Saturday said that the company would be participating in OpenAI’s latest funding round, describing it as potentially “the largest investment we’ve ever made.” “We will invest a great deal of money,” Huang told reporters while visiting Taipei. “I believe in OpenAI. The work that they do is incredible. They’re one of the most consequential companies of our time.” Huang did not say exactly how much Nvidia might contribute, but described the investment as “huge.” “Let Sam announce how much he’s going to raise — it’s for him to decide,” Huang said, referring to OpenAI

The global server market is expected to grow 12.8 percent annually this year, with artificial intelligence (AI) servers projected to account for 16.5 percent, driven by continued investment in AI infrastructure by major cloud service providers (CSPs), market researcher TrendForce Corp (集邦科技) said yesterday. Global AI server shipments this year are expected to increase 28 percent year-on-year to more than 2.7 million units, driven by sustained demand from CSPs and government sovereign cloud projects, TrendForce analyst Frank Kung (龔明德) told the Taipei Times. Demand for GPU-based AI servers, including Nvidia Corp’s GB and Vera Rubin rack systems, is expected to remain high,