From Brasilia to Seoul, finance ministers are obsessing over the US dollar. Its decline could have great impact on the global financial system.

Yet rather than asking Secretary of the Treasury John Snow if the US still favors a "strong dollar," officials should look to Asia.

Regardless of where US President George W. Bush administration wants the dollar to go, Asians have co-opted the strong-dollar policy -- and they aren't about to let go of it.

The US, meanwhile, has stolen Asia's devalue-your-way-to-growth tactic. While Snow isn't saying so, the US seems quite happy with the dollar's 10 percent drop against the yen and nearly 16 percent drop versus the euro during the past year.

All this policy co-opting amounts to a risky tug of war over the dollar.

So long as its decline is orderly, the US is happy to see exports become cheaper. But Asian central banks are stepping up dollar sales to pull the dollar the other way, fearing stronger currencies will slam growth.

Who will win this tug of war? It's anyone's guess, but the fact it's taking place offers a couple of hints about the global economic outlook.

For one thing, a dollar crisis probably won't come as soon as feared. Asian central banks, already voracious buyers of US Treasuries, would merely increase purchases to stabilize the dollar. Asia isn't known for cooperating on region-wide polices, but it agrees a weaker dollar isn't an option.

For another, a necessary adjustment in global markets is being delayed.

Even those in the deficits-don't-matter camp must wonder how long the US can live this far beyond its means. The record budget deficit is one thing, but the gaping current account deficit is a clear and present danger.

The current account deficit is more than 5 percent of GDP, a record. Unless the dollar weakens, it will continue widening, making the imbalance bigger and more dangerous as well.

It would help if Asia just left the dollar alone.

For all the good news in the region -- surging equities, booming growth and emerging middle classes -- it's stuck in a developing-nation mentality. It has been almost a decade since a rebound in Asia coincided with a global one. That, coupled with improving domestic demand, means this Asian recovery is on reasonably solid footing.

It's not just China, which grew an astounding 9.9 percent in the fourth quarter from a year earlier. Thailand and Vietnam are booming, and Hong Kong, Malaysia, Singapore and Taiwan are confounding skeptics.

South Korea, no longer in recession, is expected to grow 3 percent this year. Even deflation-plagued Japan is on the mend after 13 years in and out of recession.

While big challenges and risks remain, Asians are less concerned about a huge banking crisis in their biggest economy.

It stands to reason, then, that traders are bidding up Asian currencies. If governments are to be taken at their word -- that exchange rates should reflect economic fundamentals -- currencies should rise. Yet an exorbitant amount of time and energy still goes into holding down exchange rates.

This obsession is ironic given the dollar's role in the 1997 Asian crisis. During the 1990s, the US hogged a greater share of capital than it deserved. By acting like a huge magnet, the dollar-buying boom deprived economies like Indonesia, South Korea and Thailand of much needed investment.

It also led to risky imbalances. One was allowing an already huge US trade imbalance to widen. Another was attracting mountains of capital from Japan by way of the so-called ``yen-carry trade.'' Negligible interest rates in Japan had investors borrowing cheaply in yen and reinvesting the money in higher-returning assets like US Treasuries. Many still employ the trade.

Asians would love to see the dollar return to its mid-1990s heights. Yet efforts to boost it are leading to new asset bubbles.

The Bank of Japan alone sold a record ?20.1 trillion(US$198 billion) last year, buying US Treasuries with the proceeds. It pushed some US rates down to Japan-like levels -- US two-year notes now yield 1.60 percent.

The biggest irony is that the US could win either way at Asia's expense. If Asia lets the dollar drop, US exports and growth will get a boost and the current account bubble will narrow. If Asia continues boosting the dollar and buying Treasuries, US interest rates stay low and the US can fund ever-bigger deficits.

The former outcome would be better for Asia. While it bristles at the idea of the world's largest economy devaluing its way to prosperity, Asia's fortunes are closely tied to the US If US growth booms and consumers buy more Asian goods, wouldn't it be worth the short-term pain of stronger local currencies?

It's an end-justifies-the-means situation for Asia. The region's preoccupation with weak currencies makes little sense in the short run and even less in the long run.

All the more reason for Asia to reconsider its tug of war with Washington.

In Italy’s storied gold-making hubs, jewelers are reworking their designs to trim gold content as they race to blunt the effect of record prices and appeal to shoppers watching their budgets. Gold prices hit a record high on Thursday, surging near US$5,600 an ounce, more than double a year ago as geopolitical concerns and jitters over trade pushed investors toward the safe-haven asset. The rally is putting undue pressure on small artisans as they face mounting demands from customers, including international brands, to produce cheaper items, from signature pieces to wedding rings, according to interviews with four independent jewelers in Italy’s main

Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi has talked up the benefits of a weaker yen in a campaign speech, adopting a tone at odds with her finance ministry, which has refused to rule out any options to counter excessive foreign exchange volatility. Takaichi later softened her stance, saying she did not have a preference for the yen’s direction. “People say the weak yen is bad right now, but for export industries, it’s a major opportunity,” Takaichi said on Saturday at a rally for Liberal Democratic Party candidate Daishiro Yamagiwa in Kanagawa Prefecture ahead of a snap election on Sunday. “Whether it’s selling food or

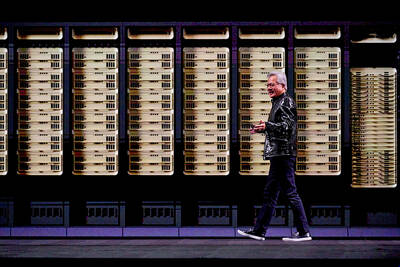

CONCERNS: Tech companies investing in AI businesses that purchase their products have raised questions among investors that they are artificially propping up demand Nvidia Corp chief executive officer Jensen Huang (黃仁勳) on Saturday said that the company would be participating in OpenAI’s latest funding round, describing it as potentially “the largest investment we’ve ever made.” “We will invest a great deal of money,” Huang told reporters while visiting Taipei. “I believe in OpenAI. The work that they do is incredible. They’re one of the most consequential companies of our time.” Huang did not say exactly how much Nvidia might contribute, but described the investment as “huge.” “Let Sam announce how much he’s going to raise — it’s for him to decide,” Huang said, referring to OpenAI

The global server market is expected to grow 12.8 percent annually this year, with artificial intelligence (AI) servers projected to account for 16.5 percent, driven by continued investment in AI infrastructure by major cloud service providers (CSPs), market researcher TrendForce Corp (集邦科技) said yesterday. Global AI server shipments this year are expected to increase 28 percent year-on-year to more than 2.7 million units, driven by sustained demand from CSPs and government sovereign cloud projects, TrendForce analyst Frank Kung (龔明德) told the Taipei Times. Demand for GPU-based AI servers, including Nvidia Corp’s GB and Vera Rubin rack systems, is expected to remain high,