It is May 2, 1945 and an airborne RAF pilot is reciting poetry with the clipped delivery of the British upper class. His plane is going down fast over the English coast as he offers his last words to June, an American wireless operator he has never met, stationed on the ground below. This is the memorable opening of A Matter of Life and Death, a British romance which, despite its 76 years, continues to hold its critical standing alongside the world’s top films.

Made by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger and starring David Niven, it is part of the canon of world cinema. And yet many British filmgoers will never have watched its vivid glories.

Three nights ago, after a decade-long wait, the results of an influential poll of the world’s greatest films prompted shock and joy in equal measure. Both Citizen Kane and Vertigo, established as bywords for the best the big screen has to offer, were dislodged from the top of the chart.

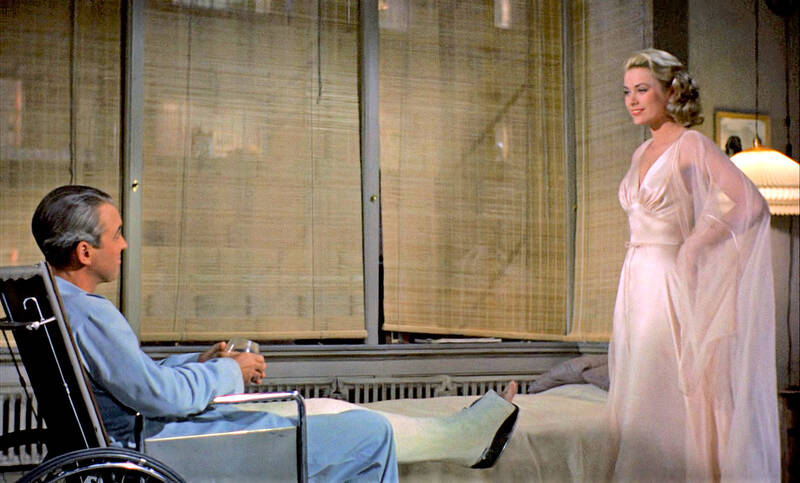

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The new winner, Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) – a comparatively little-known feminist drama by the Belgian director Chantal Akerman – is also the first film by a woman to make the top 10. Powell and Pressburger’s A Matter of Life and Death came in well below, at number 78, nine places behind their vibrant ballet drama, The Red Shoes.

This weekend, film lovers seem happy to salute this fresh list of 100 illustrious titles, published by Sight and Sound, the British Film Institute’s journal. It is a line-up compiled every 10 years from the votes of international directors, actors and critics, a constituency expanded this time to 1,639. Since the poll began in 1952, the results have been dominated by male directors, so the time was ripe, most concede, for a broader view.

True, a few commentators are quibbling about the usurping of the acknowledged “great movies” of the past in favor of more zeitgeisty offerings, such as 2019’s Oscar-winning Korean satire, Parasite, at number 90, Barry Jenkins’s story of queer identity, Moonlight, at 60, Jordan Peele’s racially astute horror debut Get Out, now at number 95, and the notable ascent of a three-year old film, Celine Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire, now at 30. Others have grumbled about a suspected “tick box” instinct among voters, allegedly prompting them to make sure that more female directors made the grade.

But as the dust settles and the list is analyzed for what it says about changing critical tastes, there is good news for the sustained power of British storytelling. Although there are now 69 different international directors, rather than 55, in the top 100, the talents of Alfred Hitchcock, Charlie Chaplin and Powell and Pressburger are still well represented, to say nothing of director Carol Reed, maker of that stylish favorite The Third Man in 1949. Seventy three years later, it holds 63rd place jointly with Goodfellas and Casablanca.

So the British titles that still ride high are rather different to the realist, kitchen-sink dramas commonly thought to characterize good British film making. Acclaimed work such as Ken Loach’s Kes or Mike Leigh’s Vera Drake — which laid the gritty groundwork for British directors working today like Clio Barnard, Lynne Ramsay or Andrea Arnold — are not so visible across the world.

“There is a colorful thread of British imaginative world-building that you can see in the directors still included in the poll,” said Isabel Stevens, managing editor of Sight and Sound. “It is an almost theatrical tradition.”

In late October of 1873 the government of Japan decided against sending a military expedition to Korea to force that nation to open trade relations. Across the government supporters of the expedition resigned immediately. The spectacle of revolt by disaffected samurai began to loom over Japanese politics. In January of 1874 disaffected samurai attacked a senior minister in Tokyo. A month later, a group of pro-Korea expedition and anti-foreign elements from Saga prefecture in Kyushu revolted, driven in part by high food prices stemming from poor harvests. Their leader, according to Edward Drea’s classic Japan’s Imperial Army, was a samurai

Located down a sideroad in old Wanhua District (萬華區), Waley Art (水谷藝術) has an established reputation for curating some of the more provocative indie art exhibitions in Taipei. And this month is no exception. Beyond the innocuous facade of a shophouse, the full three stories of the gallery space (including the basement) have been taken over by photographs, installation videos and abstract images courtesy of two creatives who hail from the opposite ends of the earth, Taiwan’s Hsu Yi-ting (許懿婷) and Germany’s Benjamin Janzen. “In 2019, I had an art residency in Europe,” Hsu says. “I met Benjamin in the lobby

April 22 to April 28 The true identity of the mastermind behind the Demon Gang (魔鬼黨) was undoubtedly on the minds of countless schoolchildren in late 1958. In the days leading up to the big reveal, more than 10,000 guesses were sent to Ta Hwa Publishing Co (大華文化社) for a chance to win prizes. The smash success of the comic series Great Battle Against the Demon Gang (大戰魔鬼黨) came as a surprise to author Yeh Hung-chia (葉宏甲), who had long given up on his dream after being jailed for 10 months in 1947 over political cartoons. Protagonist

Peter Brighton was amazed when he found the giant jackfruit. He had been watching it grow on his farm in far north Queensland, and when it came time to pick it from the tree, it was so heavy it needed two people to do the job. “I was surprised when we cut it off and felt how heavy it was,” he says. “I grabbed it and my wife cut it — couldn’t do it by myself, it took two of us.” Weighing in at 45 kilograms, it is the heaviest jackfruit that Brighton has ever grown on his tropical fruit farm, located