Sitting at the bar, martini in hand, Kristin Scott Thomas rolls her eyes briefly heavenwards.

And then she declares, in one of the most memorable monologues of the cult BBC drama Fleabag, that menopause is the “most wonderful fucking thing in the world. And yes, your entire pelvic floor crumbles and you get fucking hot and no one cares. But then — you’re free! No longer a slave, no longer a machine with parts. You’re just a person, in business.”

When an entranced Fleabag says she has been told the whole thing is horrendous, Scott Thomas’s character responds: “It is horrendous, but then it’s magnificent. Something to look forward to.”

Photo: AP

That scene, viewed about half a million times on YouTube, sticks in the mind because it represented something rare in popular culture; an older female character who actively made younger women want to be her.

“It was the first time I’d ever seen a woman in a film or a book who was frankly hot, talking about it [menopause] as a relief,” says Sam Baker, the former magazine editor whose new book The Shift describes using her own difficult menopause as a springboard to a better life. “When Fleabag tries to kiss her, and she’s like: ‘You’re lovely but I can’t be bothered’ — that was brilliant because it captured so much of what’s great about being an older woman; you know what you want, and you’re quite happy to say it.”

Her own book, she says, was born of puzzlement that even in a taboo-busting #MeToo era, female aging was still so little discussed.

Photo: AFP

“My 40s would have been so much better if I’d had someone saying: ‘This is the crap that you’re about to go through, but on the other side is this weird liberation.’”

LIFE AFTER MENOPAUSE

This autumn brings a spate of books and podcasts exploring middle-aged women’s experiences with the same raw honesty previously applied by female writers to childbirth, abortion, chronic anxiety or bad sex. Caitlin Moran’s instant bestseller More Than a Woman, sequel to her 2011 hit How To Be a Woman, includes a heart-rending account of parenting a daughter with a serious eating disorder (from which she has now thankfully recovered). Yet its upbeat central theme is older women’s resilience in coping with whatever life throws at them.

The BBC presenter Gabby Logan recently launched The Mid Point, a podcast interviewing men and women who have made midlife career changes or simply become more comfortable in their own skin.

Hot on Baker’s heels, meanwhile, comes a menopause memoir by Meg Mathews, the former music PR and fixture on the Britpop scene. Even Michelle Obama recently described on her podcast the day she had a hot flush en route to a presidential engagement, and worried she wouldn’t be able to go through with it. What happens to women’s aging bodies is, she concluded, “an important thing to take up space in a society, because half of us are going through this but we’re living like it’s not happening.” Well, no more.

Moran says of her decision to write about midlife: “The last 10 years of feminism has been brilliant and I was a part of it — writing about being a hot young mess — that’s your Fleabag and your I Will Destroy You and (new Sky Atlantic series) I Hate Suzie. It’s all about sex and periods and masturbation and that’s all been just great. But now I guess it’s the next phase of life,” she says.

“I really wanted to describe capability and strength. It’s great to talk about female vulnerability and mistakes, but you don’t really see capable women getting on with it. We don’t sell the idea of being an older woman to younger women. We don’t show that you are still the same brilliant, clever, funny person — and now you’ve also got systems, you can cope.”

‘HAGDOM’

Older women’s lives are too often written off as boring, she argues, when really they are rich with drama; these are the prime years of divorce and bereavement, of teenagers going off the rails and sorrows that can’t be easily drowned. And often all this hits just as the menopause is turning emotions upside down.

Even Moran, who at 45 is peri-menopausal rather than fully at the eye of the storm, says she can feel something changing as the softening effects of oestrogen recede.

“It’s like coming down off an E. All that kind of loving forgiveness … once it’s gone, you suddenly feel as rageful and unwilling to help people as men have all their lives. There does tend to be a sobering bit when you think: ‘Hang on, have I played myself for a mug? All those things I did, there’s no medal for it. All the time I was making a lovely cosy house, my male colleagues were putting money into ISAs.’”

Moran has, she says, now stopped running around after everyone quite as much; she takes her pleasure in friends, gardening, her dog and what she calls a happy state of “hagdom.” Even the Botox she admits to using was, she writes, less about looking younger than not wanting to look “so sad, all the time”.

Like motherhood memoirs, however, the stories that dominate are those of privileged, white, middle-class women. It’s something noted by initiatives such as the Instagram account @menopausewhilstblack (started by the fashion designer Karen Arthur, who noticed how few black women she saw publicly discussing midlife experiences), which are beginning to offer different perspectives. Yet the books are not blind to the economic consequences of aging.

Midlife is often painted as a time of tragic invisibility for women, mourning the way men’s heads no longer turn. Yet after consulting a panel of 50 women for her book, Baker concluded that “sailing under the radar of the male gaze seems to be a problem for precisely no one.”

For some, midlife was a trigger to leave dead marriages, or to explore sex with other women for the first time. What bothers older women more, she argues, is becoming professionally invisible.

“When people talk about not being whistled at by builders any more — that’s not the point, the point is suddenly men with the exact same CV are being made CEOs and you’re just … disappearing. I absolutely understand why anybody would have Botox and dye their hair, because it’s a way of dealing with it. That’s the patriarchal system you’re living in, where women’s value in particular is physical.”

Older men, she argues, are seen as having valuable professional experience, but some of the older women she interviewed complained of being told they had become “too expensive” to hire.

“Their children were no longer taking up all their time and they were all like: ‘Great, what next?’ And the world’s response is: ‘Oh, is that grey hair? No thanks.’”

Baker, who resigned as editor of the women’s glossy mag Red six years ago to launch the now defunct Web site The Pool, writes of pitching to one tech investor who announced that he liked the product but said: “I’m worried you ladies will get tired, you’re not so young any more.’”

At the time, Baker was 48 and her co-founder, Lauren Laverne, in her late 30s. No wonder, she argues, many older women are boiling with rage.

“If you look at all the things we have put up with or enabled, however you want to put it — doing more and being paid less; taking the lion’s share of the emotional and domestic labor, taking more responsibility for children — a lot of the women I spoke to said they got to around 50 and just thought: ‘Fuck this.’”

‘RIGHTEOUS FURY’

Yet the post-menopausal prize, she writes, is emerging with a new fearlessness and a “righteous fury” at injustices she had previously let slide.

Such qualities have long made older women threatening figures in patriarchal culture, which consequently tends to dismiss them as harridans, crones and battleaxes. But Baker is all for reclaiming those words.

“I honestly don’t care if someone thinks I’m an old bag now, and I would have five years ago.”

The millennial generation, now nearing 40, will, she thinks, be even less willing to go quietly.

Logan still remembers the conversation she had with a former boss at Sky TV, when she was just starting out.

“I was 24, and I said I really wanted to do live football, and he said: ‘But you won’t be on my screen after the age of 28,’” recalls Logan, now 47. “People always said to me: ‘Why are you in such a hurry?’ Well, that’s why. At 40, I couldn’t believe I was still on air.”

Times, she says, are changing even in the notoriously ageist world of TV. For her podcast she recently interviewed Claudia Winkleman, currently fronting Strictly Come Dancing aged 48; meanwhile, Joanna Lumley is presenting documentaries in her 70s.

“Now I think, why wouldn’t I be working for another 10 years in telly if I want to?”

Yet old anxieties run deep. Logan bills herself on the podcast as “middle-aged and unashamed,” a giveaway phrase if aging really is shedding its stigma.

“If you think about it, ‘that’s so middle-aged’ — it’s never said in a complimentary way. Whatever context it’s in, it’s always negative,” she concedes. “But I think midlife is a period where you grow and change.”

A woman approaching 50, she points out, still has about two decades of working life left.

“We’re not going to be retiring like previous generations, so we need to be doing things we want to do.”

It’s telling perhaps that none of these women would choose to be 35 again if they could, valuing more the lessons learned in midlife.

“The big one with my daughter is that I’m not scared of sadness any more,” says Moran. “I was so scared of being sad, and other people being sad, and now I can just sit with someone and say: ‘You’re sad, you’re angry, let’s talk about this.’” There is a brief pause, before she breaks it by adding drily: “Also, I’ve finally worked out a great storage system for my Tupperware. I will not have all lids and no boxes any more.”

Life goals, as they say.

In late October of 1873 the government of Japan decided against sending a military expedition to Korea to force that nation to open trade relations. Across the government supporters of the expedition resigned immediately. The spectacle of revolt by disaffected samurai began to loom over Japanese politics. In January of 1874 disaffected samurai attacked a senior minister in Tokyo. A month later, a group of pro-Korea expedition and anti-foreign elements from Saga prefecture in Kyushu revolted, driven in part by high food prices stemming from poor harvests. Their leader, according to Edward Drea’s classic Japan’s Imperial Army, was a samurai

The following three paragraphs are just some of what the local Chinese-language press is reporting on breathlessly and following every twist and turn with the eagerness of a soap opera fan. For many English-language readers, it probably comes across as incomprehensibly opaque, so bear with me briefly dear reader: To the surprise of many, former pop singer and Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) ex-lawmaker Yu Tien (余天) of the Taiwan Normal Country Promotion Association (TNCPA) at the last minute dropped out of the running for committee chair of the DPP’s New Taipei City chapter, paving the way for DPP legislator Su

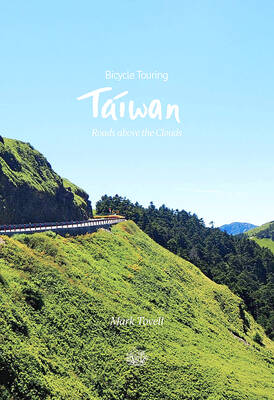

It’s hard to know where to begin with Mark Tovell’s Taiwan: Roads Above the Clouds. Having published a travelogue myself, as well as having contributed to several guidebooks, at first glance Tovell’s book appears to inhabit a middle ground — the kind of hard-to-sell nowheresville publishers detest. Leaf through the pages and you’ll find them suffuse with the purple prose best associated with travel literature: “When the sun is low on a warm, clear morning, and with the heat already rising, we stand at the riverside bike path leading south from Sanxia’s old cobble streets.” Hardly the stuff of your

Located down a sideroad in old Wanhua District (萬華區), Waley Art (水谷藝術) has an established reputation for curating some of the more provocative indie art exhibitions in Taipei. And this month is no exception. Beyond the innocuous facade of a shophouse, the full three stories of the gallery space (including the basement) have been taken over by photographs, installation videos and abstract images courtesy of two creatives who hail from the opposite ends of the earth, Taiwan’s Hsu Yi-ting (許懿婷) and Germany’s Benjamin Janzen. “In 2019, I had an art residency in Europe,” Hsu says. “I met Benjamin in the lobby