When a group of Taiwanese students in Norway sued the Norwegian government last year for changing the nationality on their residency permits to China, they naturally engaged a lawyer to fight their legal battles. But to win over the court of public opinion, they would need a very different kind of representation.

Enter the Taiwan Digital Diplomacy Association (台灣數位外交協會, TDDA). Founder Kuo Chia-yo (郭家佑), 28, tells the Taipei Times that the group will be helping the Taiwanese students with their digital outreach this year. It’s one of several digital diplomacy projects the non-government organization has taken on since its establishment in 2017.

Using new digital tools and social media, coupled with old-fashioned cultural observation, TDDA is spearheading a unique approach to boost Taiwan’s profile on the global stage, and broaden the nation’s constrained space for international exchanges. Its work is also filling a notable gap in Taiwan’s official approach to public diplomacy.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Digital Diplomacy Association

GRASSROOTS DIPLOMACY

“We’re not like a typical government project that goes out to promote Taiwan by saying we’re great or asking everyone to come check us out,” Kuo says. “Our approach is more like networking, to find things that we can do together with locals [of other countries] on social media.”

TDDA is a lean outfit, with only two full-time and eight part-time staff, but its reach is imaginative. Kuo, who now flits between Taipei and Ho Chi Minh City, has so far taken the organization to Kosovo and Vietnam.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Digital Diplomacy Association

In Kosovo, a landlocked state in Southeastern Europe, Taiwan has a natural friend in the shared experience of being a country with only partial international recognition.

In 2017, TDDA ran a social media campaign advocating Kosovo’s digital independence by having its own national Internet domain. A video of young Taiwanese declaring their support for Kosovo attracted 32,000 views on Facebook, gaining precious traction for Taiwan in the nation of nearly two million.

Last summer, the group worked with the Kosovo Cultural Exchange Association to produce an exhibition on visions of Kosovo’s future at the national museum in the capital Pristina. The project involved Taiwanese designers and interactive digital exhibitions such as a “democracy wall,” where visitors voted for the social changes they most desired to see in Kosovo.

In Vietnam, TDDA has set up Taiwan Corner, a cafe and exhibition space, and produced an Internet medical talkshow series featuring a panel of Vietnamese doctors talking about medical issues that locals commonly face.

If the links to Taiwan seem indirect, that’s the intention. The idea is to earn Taiwan more friends and supporters by first showing a concern for causes that are important to the citizens of other countries.

For its projects in Vietnam, the organization has also worked closely with Vietnamese students in Taiwan, further strengthening offline, people-to-people ties between the two countries.

Kuo sees this as a way of forging connections that are more resilient to geopolitical power dynamics, especially in the face of growing Chinese pressure that has seen the number of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies fall to 15.

“When people really see you as a friend, they won’t cut you off just because of China,” Kuo says. “What will get cut off is government relations, but not people-to-people connections.”

SOCIAL MEDIA PROFILE

With the proliferation of social media and data-driven technologies, the use of digital diplomacy to win over hearts and minds abroad is a growing priority for foreign offices around the world.

In particular, digital diplomacy is proving to be an essential tool where there are no formal diplomatic ties. Israel’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs runs several Arabic-language social media platforms to reach out to the citizens of Arab countries with which the country does not have diplomatic relations.

The potential for Taiwan, which boasts a high Internet and smartphone penetration rate, is obvious. Yet there are still disparities between the government’s grasp of social media for domestic and international audiences.

While the government already leverages Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, LINE and local influencers for domestic messaging, digital diplomacy directed at the rest of the world has developed at a much slower pace.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs only started a Twitter account in April 2018, and Kuo cites the fact that the country’s overseas representative offices have only recently started making their social media posts in English or the vernacular language.

Kosovo’s digital independence and the medical concerns of Vietnamese may seem remote from Taiwan’s international standing, but these are issues that TDDA landed on after building social media profiles of both countries. The objective is to identify causes that Taiwanese and citizens of that country can work on together, exchanging their shared values.

Kuo says that it takes the team several months to trawl through social media profiles, groups and hashtags to gain a feel for the preoccupations of their citizens and their impressions of Taiwan.

For example, TDDA conceptualized the medical talkshow after their efforts revealed that health is one of the top discussion topics for Vietnamese on social media, but that few think of Taiwan as a destination for medical tourism.

TDDA is still in the midst of building its digital strategy for the Taiwanese students’ lawsuit against Norway, but Kuo says that for a start, they plan to use Norwegians’ love of music to familiarize them with Taiwan.

These are skills that TDDA wants to impart to more young Taiwanese. At a digital diplomacy workshop in May last year, participants found that when it comes to Taiwan, East Asians concern themselves with the country’s tourism offerings and elections, Eastern and Southern Europeans think of restaurants and an air gun shop called Taiwan Gun, while Latin Americans have developed a taste for Taiwanese drama serials. Most Africans, however, have no impression of the country.

Such social media insights provide rare granular detail for understanding how Taiwan is perceived internationally.

Kuo still faces challenges in forging the local connections needed to get TDDA’s projects off the ground, and her own family’s inability to understand her unconventional career path. But she believes that the value of digital diplomacy will only strengthen for Taiwan’s future generations of digital natives.

“In the past they might have felt that diplomacy is something the government does and it has no connection to me. But now, because the channels that we use are social media, it’s something that everyone knows. So more people feel that actually, they can do something,” Kuo says.

In late October of 1873 the government of Japan decided against sending a military expedition to Korea to force that nation to open trade relations. Across the government supporters of the expedition resigned immediately. The spectacle of revolt by disaffected samurai began to loom over Japanese politics. In January of 1874 disaffected samurai attacked a senior minister in Tokyo. A month later, a group of pro-Korea expedition and anti-foreign elements from Saga prefecture in Kyushu revolted, driven in part by high food prices stemming from poor harvests. Their leader, according to Edward Drea’s classic Japan’s Imperial Army, was a samurai

The following three paragraphs are just some of what the local Chinese-language press is reporting on breathlessly and following every twist and turn with the eagerness of a soap opera fan. For many English-language readers, it probably comes across as incomprehensibly opaque, so bear with me briefly dear reader: To the surprise of many, former pop singer and Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) ex-lawmaker Yu Tien (余天) of the Taiwan Normal Country Promotion Association (TNCPA) at the last minute dropped out of the running for committee chair of the DPP’s New Taipei City chapter, paving the way for DPP legislator Su

Located down a sideroad in old Wanhua District (萬華區), Waley Art (水谷藝術) has an established reputation for curating some of the more provocative indie art exhibitions in Taipei. And this month is no exception. Beyond the innocuous facade of a shophouse, the full three stories of the gallery space (including the basement) have been taken over by photographs, installation videos and abstract images courtesy of two creatives who hail from the opposite ends of the earth, Taiwan’s Hsu Yi-ting (許懿婷) and Germany’s Benjamin Janzen. “In 2019, I had an art residency in Europe,” Hsu says. “I met Benjamin in the lobby

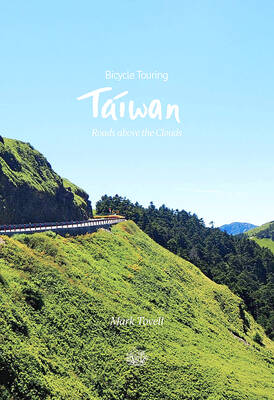

It’s hard to know where to begin with Mark Tovell’s Taiwan: Roads Above the Clouds. Having published a travelogue myself, as well as having contributed to several guidebooks, at first glance Tovell’s book appears to inhabit a middle ground — the kind of hard-to-sell nowheresville publishers detest. Leaf through the pages and you’ll find them suffuse with the purple prose best associated with travel literature: “When the sun is low on a warm, clear morning, and with the heat already rising, we stand at the riverside bike path leading south from Sanxia’s old cobble streets.” Hardly the stuff of your