Over 70 years on, memories of a half-century of Japanese colonization may have dimmed, but its legacy lives on in, not least in the many Japanese-era buildings found in the cities of Taiwan’s coastal plains, from Keelung to Kaohsiung.

Although forced to leave Taiwan at the end of the Second World War, the Japanese left evidence of their control of the nation’s main island not only in sumptuous, Western-inspired architecture and a much-improved road network, but also in a series of secondary routes across the central mountains that could only be followed on foot or horseback. These military communication arteries were primarily intended to suppress the island’s Aborigines, and at regular intervals along each was a police outpost or fort.

A few routes from that time, for instance the epic, 125-km Batongguan Traversing Trail (八通關越道), and the much shorter Paoma (“running horse”) Old Trail (跑馬古道) in Yilan County, have been cleared for hikers to follow. The majority, though, are either only very occasionally visited by intrepid hiking groups, or have been completely lost to the returning jungle, and today exist only on hiking maps as lines marking non-existent trails, or the names of former settlements and military camps deep in the virtually inaccessible central mountains.

Photo: Richard Saunders

Very few physical remains of these mountain forts, police outposts and settlements can be seen today, although several popular trails (including the Walami Trail, 瓦拉米步道, in southern Hualien County and the Zhuilu Old Trail, 錐麓古道, in Taroko Gorge) pass the flat, open areas where they once stood. I can think of only two Japanese forts in Taiwan’s mountainous interior that survive reasonably intact. One is just off the South Cross-island Highway in Taitung County, and the second is Lidong Fort (李崠山古堡), atop a 2,000-meter-high mountain in Hsinchu County.

The old fort atop Mount Lidong is perhaps the most interesting Japanese-built fortification on the island. The fort dates from the early years of the colonial period.

After landing on Taiwan on March 29, 1895, Japanese soldiers quickly spread across the island, subduing resistance, and although small groups of rebel Han Chinese forces held out for a while in several mountain areas in the north of the island, most of Taiwan’s heavily populated lowland areas were under Japanese control by the end of that year.

Photo: Richard Saunders

Subduing the island’s aboriginal peoples, who had been pushed by several centuries of Han migration deep into the central mountains, proved a much tougher job, and one that was left to General Count Sakuma Samata (佐久間左馬太), who was named the fifth Governor-General of Taiwan in April 1906.

Samata immediately buckled down to the job of teaching the Atayal aboriginals of northern Taiwan to bow to authority. He began a five-year campaign, during which he led several armed attacks against them. During a 1911 campaigns, an army of 2,000 troops set out to take Mount Lidong, capturing it after heavy fighting, which resulted in heavy casualties on both sides. A fort was built on the site, and strengthened the following year after continuing resistance from the Atayal, who finally gave up the fight in 1913.

Today all that remains of the fort are its four walls, which enclose a rectangular area 28 meters by 22 meters. The walls, about three meters high, are just over half a meter thick. Despite its military function, the Japanese couldn’t resist throwing a little style into the design; the main entrance gate is rather fine, although a plaque that once hung above the entrance arch has disappeared. There’s little to explore inside: the structure is essentially an empty shell with a collection of radio aerials and a trig point in the middle.

Photo: Richard Saunders

Apart from its interesting history, the main reason to visit Mount Lidong Fort is its location. Perched atop a mountain at 1,913 meters, it makes a great trip, first by vehicle and then on foot, into one of northern Taiwan’s remoter corners.

Arriving at the trailhead, it’s impossible to miss the richly eccentric Mount Lidong Villa (李崠山莊), and its tumbledown hotchpotch of ornamental pavilions, covered terraces, corridors and footbridges is something of an attraction in its own right. As you pass through you’ll almost certainly meet and get to chat with the shelter’s friendly owner, a retired army soldier who collects a small fee for the privilege of sweating up the steep, hour-long trail to the fort.

There’s a height increase of 400 meters between the villa and the fort, and the trail (clearly marked with signposts and plastic trail-marking ribbons) is a seemingly endless series of steep zigzags. After about half-an-hour, the trail meets a stony track which leads to the summit and the fort. Follow either the easier winding track, or take the much steeper short-cuts that intersect it at intervals, and about an hour after leaving the villa, the gateway of Mt. Lidong Fort looms out of the fast-encroaching forest.

Photo: Richard Saunders

There’s a fantastic view over the central mountain range if you can find a break in the tall grass and trees that now encircle the fort walls; otherwise climb a few meters up the ladder serving one of the aerials inside the fort. Snow Mountain (雪山), Taiwan’s second highest and Mount Nanhuda (南湖大山), its fifith, are visible on a clear day. But even if the mist has already rolled in, defeating any ambitions of enjoying the superb panorama, the dead silence and slightly eerie atmosphere of the site makes it a place to linger awhile, before heading down for another chat, and perhaps a cup of tea, back at the trailhead.

Richard Saunders is a classical pianist and writer who has lived in Taiwan since 1993. He’s the founder of a local hiking group, Taipei Hikers, and is the author of six books about Taiwan, including Taiwan 101 and Taipei Escapes. Visit his Web site at www.taiwanoffthebeatentrack.com.

In late October of 1873 the government of Japan decided against sending a military expedition to Korea to force that nation to open trade relations. Across the government supporters of the expedition resigned immediately. The spectacle of revolt by disaffected samurai began to loom over Japanese politics. In January of 1874 disaffected samurai attacked a senior minister in Tokyo. A month later, a group of pro-Korea expedition and anti-foreign elements from Saga prefecture in Kyushu revolted, driven in part by high food prices stemming from poor harvests. Their leader, according to Edward Drea’s classic Japan’s Imperial Army, was a samurai

The following three paragraphs are just some of what the local Chinese-language press is reporting on breathlessly and following every twist and turn with the eagerness of a soap opera fan. For many English-language readers, it probably comes across as incomprehensibly opaque, so bear with me briefly dear reader: To the surprise of many, former pop singer and Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) ex-lawmaker Yu Tien (余天) of the Taiwan Normal Country Promotion Association (TNCPA) at the last minute dropped out of the running for committee chair of the DPP’s New Taipei City chapter, paving the way for DPP legislator Su

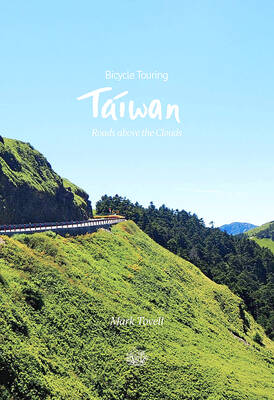

It’s hard to know where to begin with Mark Tovell’s Taiwan: Roads Above the Clouds. Having published a travelogue myself, as well as having contributed to several guidebooks, at first glance Tovell’s book appears to inhabit a middle ground — the kind of hard-to-sell nowheresville publishers detest. Leaf through the pages and you’ll find them suffuse with the purple prose best associated with travel literature: “When the sun is low on a warm, clear morning, and with the heat already rising, we stand at the riverside bike path leading south from Sanxia’s old cobble streets.” Hardly the stuff of your

Located down a sideroad in old Wanhua District (萬華區), Waley Art (水谷藝術) has an established reputation for curating some of the more provocative indie art exhibitions in Taipei. And this month is no exception. Beyond the innocuous facade of a shophouse, the full three stories of the gallery space (including the basement) have been taken over by photographs, installation videos and abstract images courtesy of two creatives who hail from the opposite ends of the earth, Taiwan’s Hsu Yi-ting (許懿婷) and Germany’s Benjamin Janzen. “In 2019, I had an art residency in Europe,” Hsu says. “I met Benjamin in the lobby