Thank goodness that US President Donald Trump did not — despite speculation that he might — meet North Korean leader Kim Jong-un while the US president was visiting the Korean peninsula last month for an economic gathering.

That is because “we’re not ready for a summit” between these two, and “if there is another summit, it might end very badly,” said Joel Wit, distinguished fellow at the Stimson Center.

Wit should know. He has been either participating in or observing the fraught relations between the US and North Korea since the 1990s, when he was at the US Department of State, and helped negotiate and implement the so-called Agreed Framework. It was supposed to freeze North Korea’s nuclear program in return for fuel oil and light-water reactors from the US. Instead, the North Koreans kept building their weapons in secret and the agreement collapsed. So did all other US attempts to denuclearize the Kim dynasty, a history of failure that Wit chronicles in his new book.

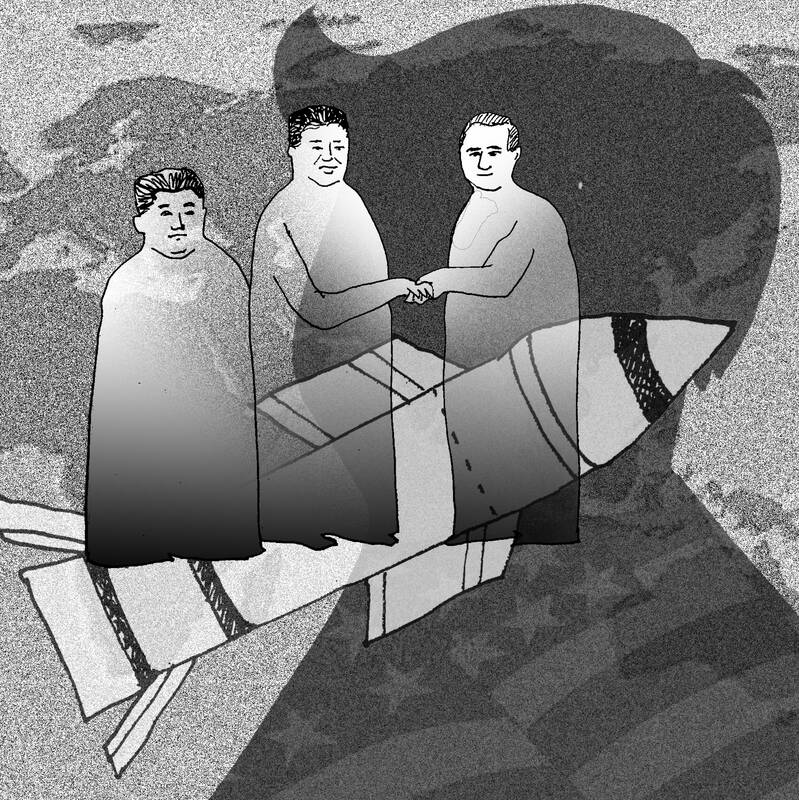

Illustration: Tania Chou

Today, North Korea is estimated to have between 50 and 90 nukes, and all manner of delivery vehicles, including ones that can reach the continental US — the resulting anxieties about nuclear Armageddon captivate even Hollywood. Uncomfortably for Trump, he, like at least four of his predecessors, bears part of the blame, not least for the three flashy but failed summits he held with Kim in his first term.

The problem is not just that Trump overestimates himself as a dealmaker and peacemaker, it is also that he would not listen to advisers because “he thinks, because he had three summits with Kim, that no one knows him better,” Wit said.

Worse yet, Trump thinks he is still “dealing with the North Korea of 2019,” he added.

Instead, the geopolitical and strategic situation has changed beyond recognition, and unambiguously to the detriment of the US side.

To understand those changes, I asked Robert Carlin, another veteran of the US’ attempts to denuclearize North Korea — he used to run the State Department’s in-house intelligence gathering about the Korean peninsula and is now, like Wit, at the Stimson Center.

Here is the contrast between Pyongyang’s position and mindset then — from the 1990s to roughly the Trump-Kim summits — and now:

Back then, North Korea was isolated. Even Russia and China were working with the US toward Pyongyang’s denuclearization — within the so-called Six-Party Talks and on the UN Security Council. As a result, then-North Korean leader Kim Jong-il and later his son, who wanted to modernize North Korea’s economy, craved a normalization of relations with Washington. US presidents could dangle this prospect as a big carrot.

Simultaneously, the US wielded a big stick, in the form of sanctions, which China and Russia, more or less, helped to enforce. In the background, US troops in South Korea and the US nuclear umbrella seemed effective deterrents against North Korean aggression.

All that has changed. Today, North Korea is no longer isolated. Instead, it has a mutual defense treaty with Russia and sent its troops to fight alongside Russian forces against Ukraine. It has also warmed up ties to its old ally China. Meeting in Beijing in September, Kim, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) beamed with confidence and comity and looked mightily like an emerging anti-US “axis.”

Far from collaborating with the US toward denuclearization on the peninsula, Moscow and Beijing nowadays protect Pyongyang on the UN Security Council.

So Kim no longer needs normalization with the US. Nor is he worried about US attempts to add sanctions, because China and Russia would help him evade those even more brazenly than they did in the past. Both the carrot and the stick are gone.

Worse, Kim, with his arsenal of nukes and his alignment with Moscow and Beijing, is no longer awestruck by the US military. Kim has concluded that the US and its commitment to its allies are weakening and “sees himself as a leading anti-imperialist,” Carlin said; “as one of the big guys” — with Putin and Xi — who will “push the Americans back, and off the peninsula.”

Carlin believes that Kim “thinks that he can now get away with things, even an attack on South Korea.”

It cannot even be ruled out that such an assault might be coordinated with simultaneous aggressions by Russia in eastern Europe or China in the Taiwan Strait. Deterrence does not work anymore, Carlin added.

Nobody in Washington seems to have any idea about how to get new sticks and carrots, but Carlin and Wit are clear about at least one way to stop making this bad situation worse: It is to affirm rather than undermine the US’ alliances, especially those with South Korea and Japan, to shore up whatever remains of deterrence as long as possible.

Instead, Trump sees allies, including South Korea, as free-riders that deserve tariffs. He is correct in demanding that South Korea — like the NATO allies — shoulder more of its own defense burden. However, as Washington and Seoul discuss “modernizing” the alliance, he also keeps resurfacing the option of gradually withdrawing US troops (or perhaps moving them to Guam).

Whether Trump would retaliate against Pyongyang in the event of a pre-emptive nuclear strike by the North on the South — and risk “trading San Francisco for Seoul” — is moot.

In the worst case, which seems increasingly likely, South Korea and maybe Japan would conclude that they need their own nuclear weapons and build them. While they are getting ready, Kim would be even more tempted to strike first.

At that point, if not already, “too many different hands are holding matches in a room full of gasoline fumes,” Wit said.

Columnists are supposed to offer solutions: “Don’t just push a button and throw out suggestions,” Carlin said. “The first step is coming to grips with the new reality.”

Nothing suggests that Trump or his national-security team have done that. In his eagerness to proclaim a “deal,” Trump might instead give Kim too much in return for nothing of substance, throwing Seoul under the bus. If Trump rushed into a summit with Kim now, he might get played as he did with Putin.

The quest to denuclearize the Korean peninsula has failed and can no longer be the objective of US policy. The goal must instead be to stabilize East Asia to reduce the risk of war, including the nuclear kind. To that end, the US must find answers to the composite threat of Russia, China and North Korea. For the sake of honesty, a good start might be to admit that so far it does not have any.

Andreas Kluth is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering US diplomacy, national security and geopolitics. Previously, he was editor-in-chief of Handelsblatt Global and a writer for The Economist. This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Lockheed Martin on Tuesday responded to concerns over delayed shipments of F-16V Block 70 jets, saying it had added extra shifts on its production lines to accelerate progress. The Ministry of National Defense on Monday said that delivery of all 66 F-16V Block 70 jets — originally expected by the end of next year — would be pushed back due to production line relocations and global supply chain disruptions. Minister of National Defense Wellington Koo (顧立雄) said that Taiwan and the US are working to resolve the delays, adding that 50 of the aircraft are in production, with 10 scheduled for flight

Victory in conflict requires mastery of two “balances”: First, the balance of power, and second, the balance of error, or making sure that you do not make the most mistakes, thus helping your enemy’s victory. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has made a decisive and potentially fatal error by making an enemy of the Jewish Nation, centered today in the State of Israel but historically one of the great civilizations extending back at least 3,000 years. Mind you, no Israeli leader has ever publicly declared that “China is our enemy,” but on October 28, 2025, self-described Chinese People’s Armed Police (PAP) propaganda

Chinese Consul General in Osaka Xue Jian (薛劍) on Saturday last week shared a news article on social media about Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi’s remarks on Taiwan, adding that “the dirty neck that sticks itself in must be cut off.” The previous day in the Japanese House of Representatives, Takaichi said that a Chinese attack on Taiwan could constitute “a situation threatening Japan’s survival,” a reference to a legal legal term introduced in 2015 that allows the prime minister to deploy the Japan Self-Defense Forces. The violent nature of Xue’s comments is notable in that it came from a diplomat,

The artificial intelligence (AI) boom, sparked by the arrival of OpenAI’s ChatGPT, took the world by storm. Within weeks, everyone was talking about it, trying it and had an opinion. It has transformed the way people live, work and think. The trend has only accelerated. The AI snowball continues to roll, growing larger and more influential across nearly every sector. Higher education has not been spared. Universities rushed to embrace this technological wave, eager to demonstrate that they are keeping up with the times. AI literacy is now presented as an essential skill, a key selling point to attract prospective students.