Qatar is a rich Persian Gulf nation known for its huge oil reserves and its flagrant human rights abuses. It is a dictatorship in which women have to seek permission from their male guardians to marry or work in many government jobs, in which being gay is criminalized and can result in a prison sentence, in which migrant workers are treated appallingly and in which journalists have been imprisoned for reporting critically on domestic politics.

Yet all of this is minimized as the world’s eyes fall on Qatar for the start of the 2022 FIFA World Cup next month. Qatar’s leaders know this and it is why they have paid through the nose — estimates put it at US$220 billion, by far the most expensive World Cup of all time — to host the competition, including lavishing money on efforts to lobby British politicians.

Inevitably, soccer teams, international supporters, the world’s media and foreign dignitaries would duly head to Qatar for an international sporting tournament that has serious environmental implications and could, some predict, leave a huge carbon footprint.

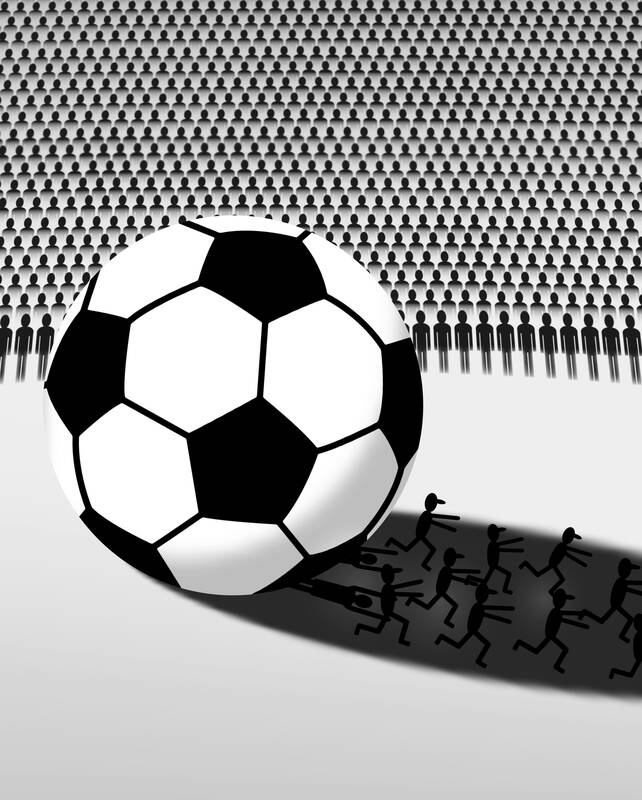

Illustration: Yisha

At a conservative estimate, at least 6,500 migrant workers have lost their lives in Qatar since it was awarded the World Cup in 2011.

This World Cup is just the latest in a long line of expensive international sporting events that have been hosted by nations that stand accused of fundamental human rights contraventions.

The 2008 Summer Olympics and this year’s Winter Olympics in China, the 2014 Winter Olympics in Russia, the Bahrain Grand Prix, the 2019 World Athletics Championships in Qatar and the 2019 Anthony Joshua fight in Saudi Arabia: There is an indisputable trend of big sporting events being hosted by rich but unsavory countries.

This is the reflection of a number of trends. There is the push factor of dictatorships around the world seeking to launder their reputations through the medium of international sport — US$200 billion on a World Cup does not just secure international visitors and sporting entertainment, but also publicity that money normally cannot buy. This is particularly valuable in an age when Gulf states recognize that at some point the oil and gas will run out and so are looking to build other sources of power on the world stage.

In response, competitions are more expensive to put on, as democracies that have to justify the expense to voters get priced out of the market. The 2006 World Cup in Germany cost just US$4.3 billion. The levels of financial corruption in international sport — governing bodies such as FIFA and the International Olympic Committee have been notoriously porous to expensive bribes and shady deals in exchange for votes behind the scenes — have made things worse.

Sporting bureaucrats therefore often face unenviable choices. For example, between Beijing in China and Almaty in Kazakhstan for this year’s Winter Olympics, which ultimately went to the former, necessitating the manufacture of fake snow out of 185 million liters of water.

Sports governing bodies advance the case that awarding competitions to countries with questionable human rights records draws attention and scrutiny to their abuses, encouraging liberalization.

World Athletics president Sebastian Coe claimed at the 2019 World Athletics Championships in Qatar that sport can uniquely “shine the spotlight on issues” and is “the best diplomat we have.”

However, there is little academic evidence of these effects. China’s human rights abuses got worse between the 2009 Summer Olympics and this year’s Winter Olympics. The same is true of Russia and the 2014 Sochi Olympics. The 1936 Berlin Olympics were undoubtedly a propaganda coup for the Nazis.

Sporting competitions would lead to improvements only if sports bodies were to take a tough approach with host nations, attaching stringent conditions that improve human rights records beyond the period of the competition itself.

However, they are generally not willing to do this. In fact, they are much more likely to equivocate and protest their neutrality over the most dreadful human rights abuses.

When asked what he would say to Chinese Uighurs forcibly separated from their children and interned in concentration camps, International Olympic Committee (IOC) president Thomas Bach said on the eve of this year’s Beijing Olympics: “The position of the IOC must be to give political neutrality. If we get in the middle of intentions and disputes and confrontations of political powers, then we are putting the games at risk.”

Could there be anything more morally decrepit than a policy of neutrality on genocide?

The problem does not start and stop with sport. The approach international sports bodies take to countries such as the Gulf states is a reflection of international politics. Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates are considered close allies of the UK, with cooperation on security and the fostering of trade links, including arms sales.

The British Royal Air Force even has a joint air force squadron with Qatar. Earlier this year, then-British prime minister Boris Johnson went to Saudi Arabia to meet Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, despite the fact that his government had arranged for the Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi to be murdered in its consulate in Istanbul in 2018.

International sporting competitions should not be awarded to governments with appalling human rights records.

However, this is a line that Western political, not just sporting, leadership has proved all too willing to cross.

Could Asia be on the verge of a new wave of nuclear proliferation? A look back at the early history of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), which recently celebrated its 75th anniversary, illuminates some reasons for concern in the Indo-Pacific today. US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin recently described NATO as “the most powerful and successful alliance in history,” but the organization’s early years were not without challenges. At its inception, the signing of the North Atlantic Treaty marked a sea change in American strategic thinking. The United States had been intent on withdrawing from Europe in the years following

My wife and I spent the week in the interior of Taiwan where Shuyuan spent her childhood. In that town there is a street that functions as an open farmer’s market. Walk along that street, as Shuyuan did yesterday, and it is next to impossible to come home empty-handed. Some mangoes that looked vaguely like others we had seen around here ended up on our table. Shuyuan told how she had bought them from a little old farmer woman from the countryside who said the mangoes were from a very old tree she had on her property. The big surprise

The issue of China’s overcapacity has drawn greater global attention recently, with US Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen urging Beijing to address its excess production in key industries during her visit to China last week. Meanwhile in Brussels, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen last week said that Europe must have a tough talk with China on its perceived overcapacity and unfair trade practices. The remarks by Yellen and Von der Leyen come as China’s economy is undergoing a painful transition. Beijing is trying to steer the world’s second-largest economy out of a COVID-19 slump, the property crisis and

As former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) wrapped up his visit to the People’s Republic of China, he received his share of attention. Certainly, the trip must be seen within the full context of Ma’s life, that is, his eight-year presidency, the Sunflower movement and his failed Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement, as well as his eight years as Taipei mayor with its posturing, accusations of money laundering, and ups and downs. Through all that, basic questions stand out: “What drives Ma? What is his end game?” Having observed and commented on Ma for decades, it is all ironically reminiscent of former US president Harry