The EU is emerging as the world’s climate trailblazer. Last week, EU lawmakers and European governments agreed on the European Climate Law, anchoring our climate-neutrality target in statute. With the “green deal” as our growth strategy and our 2030 emissions-reduction target of at least 55 percent, the EU is well on the way to achieving climate neutrality by 2050.

However, Europe is not alone: A critical mass is developing globally as more countries bolster their decarbonization commitments.

Recent meetings with US Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry confirmed that the EU and the US are once again working closely to mobilize an international coalition around the goal of substantially raising climate ambitions for the UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow in November.

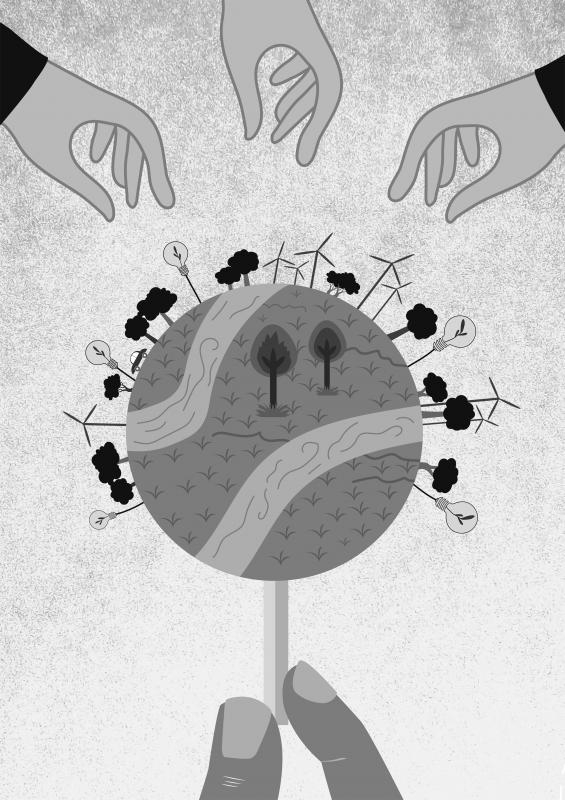

Illustration: Lance Liu

There is no time to lose. Unchecked climate change — with its devastating droughts, famines, floods and mass dislocations — would fuel new migration waves and significantly increase the frequency and intensity of conflicts over water, arable land and natural resources.

To those who complain about the large investments needed to tackle climate change and biodiversity loss, we would simply point out that inaction would cost far more.

By tackling the climate and biodiversity crises, everyone will be better off, thanks to better jobs, cleaner air and water, fewer pandemics and improved health and well-being.

However, as with any broad transition, the coming changes will upset some and benefit others, creating tensions within and between countries. As we accelerate the transition from a hydrocarbon-based economy to a sustainable one based on renewable energy, we cannot be blind to these geopolitical effects.

In particular, the transition itself will drive power shifts away from those controlling and exporting fossil fuels toward those mastering the green technologies of the future.

For example, phasing out fossil fuels will significantly improve the EU’s strategic position, not least by reducing its reliance on energy imports.

In 2019, 87 percent of our oil and 74 percent of our gas came from abroad, requiring us to import more than 320 billion euros (US$388 billion at the current exchange rate) worth of fossil-fuel products that year.

Moreover, with the green transition, the old strategic choke points — starting with the Strait of Hormuz — will become less relevant and thus less dangerous.

These seaborne passages have preoccupied military strategists for decades, but as the oil age passes, they will be less subject to competition for access and control by regional and global powers.

Phasing out energy imports will also help reduce the income and geopolitical power of countries like Russia, which relies heavily on the EU market.

Of course, the loss of this key source of Russian revenue could lead to instability in the near term, particularly if the Kremlin sees it as an invitation to adventurism.

In the long term, a world run on clean energy could also be a world of cleaner government, because traditional fossil-fuel exporters will need to diversify their economies, and free themselves from the “oil curse” and the corruption it so often fosters.

However, at the same time, the green transition itself will require scarce raw materials, some of which are concentrated in countries that have already shown a willingness to use natural resources as foreign-policy tools. This growing vulnerability will need to be addressed in two ways: by recycling more of these key resources and by forging broader alliances with exporting countries.

Moreover, as long as other countries’ climate commitments are not on par with our own, there will be a risk of “carbon leakage.” That is why the EU is working on a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM).

We know that some countries, even among our allies, are concerned about this.

However, we want to be clear: Setting a price on imported carbon-intensive goods is not meant to be punitive or protectionist.

In addition to ensuring that our plans are compliant with WTO rules, we will engage with our international partners early on to explain what we have in mind. Our goal is to facilitate cooperation and help others reach their climate targets.

We hope that the CBAM will trigger a race to the top.

Although the green transition will bring about more sustainable and resilient economies, it will not automatically usher in a world with less conflict or geopolitical competition.

The EU, harboring no illusions, will need to analyze the impact of its policies across different regions, recognizing the likely consequences and planning for the foreseeable risks.

For example, in the Arctic, where temperatures are rising twice as fast as the global average, Russia, China and others are already trying to establish a geopolitical foothold over territory and resources that were once under ice.

While all of these powers have a strong interest in reducing tensions and “keeping the Arctic in the Arctic,” the scramble for position is putting the entire region at risk.

To Europe’s south, there is enormous potential to generate energy from solar and hydrogen, and to establish new sustainable growth models based on renewable energy. Europe will need to cooperate closely with the countries of sub-Saharan Africa and elsewhere to seize these opportunities.

The EU has embarked on a green transition because science tells us that we must, economics teaches us that we should and technology shows us that we can.

We are convinced that a world run on clean technology would benefit people’s well-being and political stability.

However, the road to get there will be fraught with risks and obstacles.

That is why the geopolitics of climate change must inform all of our thinking.

Geopolitical risk is no excuse to alter our course or reverse direction. Rather, it is an impetus to accelerate our work toward a just transition for all. The sooner we can ensure that global public goods are there for everyone to enjoy, the better.

Frans Timmermans is executive vice president of the European Commission. Josep Borrell, EU high representative for foreign affairs and security policy, is vice president of the European Commission.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

Could Asia be on the verge of a new wave of nuclear proliferation? A look back at the early history of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), which recently celebrated its 75th anniversary, illuminates some reasons for concern in the Indo-Pacific today. US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin recently described NATO as “the most powerful and successful alliance in history,” but the organization’s early years were not without challenges. At its inception, the signing of the North Atlantic Treaty marked a sea change in American strategic thinking. The United States had been intent on withdrawing from Europe in the years following

My wife and I spent the week in the interior of Taiwan where Shuyuan spent her childhood. In that town there is a street that functions as an open farmer’s market. Walk along that street, as Shuyuan did yesterday, and it is next to impossible to come home empty-handed. Some mangoes that looked vaguely like others we had seen around here ended up on our table. Shuyuan told how she had bought them from a little old farmer woman from the countryside who said the mangoes were from a very old tree she had on her property. The big surprise

The issue of China’s overcapacity has drawn greater global attention recently, with US Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen urging Beijing to address its excess production in key industries during her visit to China last week. Meanwhile in Brussels, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen last week said that Europe must have a tough talk with China on its perceived overcapacity and unfair trade practices. The remarks by Yellen and Von der Leyen come as China’s economy is undergoing a painful transition. Beijing is trying to steer the world’s second-largest economy out of a COVID-19 slump, the property crisis and

Former president Ma Ying-jeou’s (馬英九) trip to China provides a pertinent reminder of why Taiwanese protested so vociferously against attempts to force through the cross-strait service trade agreement in 2014 and why, since Ma’s presidential election win in 2012, they have not voted in another Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) candidate. While the nation narrowly avoided tragedy — the treaty would have put Taiwan on the path toward the demobilization of its democracy, which Courtney Donovan Smith wrote about in the Taipei Times in “With the Sunflower movement Taiwan dodged a bullet” — Ma’s political swansong in China, which included fawning dithyrambs