Only five years ago, then-British prime minister David Cameron was celebrating a “golden era” in UK-China relations, bonding with Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) over a pint of beer at the pub and signing off on billions in trade deals.

Those friendly scenes now seem like a distant memory.

Hostile rhetoric has ratcheted up in recent days over Beijing’s new National Security Law for Hong Kong. Britain’s decision to offer refuge to millions in the former colony was met with a stern telling-off by Beijing, and Chinese officials have threatened “consequences” if Britain treats it as a “hostile country,” and decides to cut Chinese technology giant Huawei out of its critical telecoms infrastructure amid growing unease over security risks.

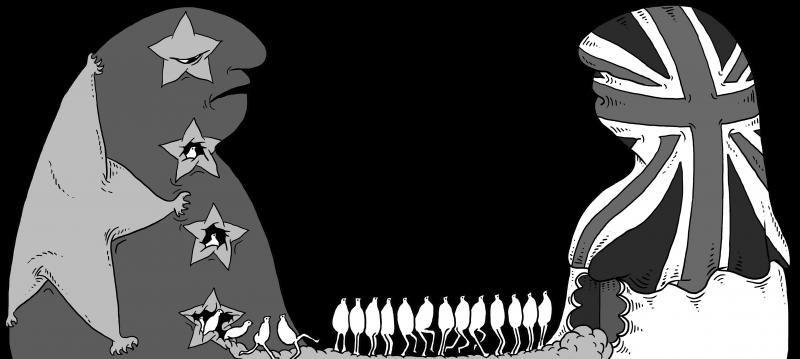

Illustration: Mountain People

All that is pointing to a much tougher stance against China, with a growing number in Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s Conservative Party taking a long, hard look at Britain’s Chinese ties.

Many are saying Britain has been far too complacent and naive in thinking it could reap economic benefits from the relationship without political consequences.

“It’s not about wanting to cut ties with China. It’s that China is itself becoming a very unreliable and rather dangerous partner,” British MP and former Conservative leader Iain Duncan Smith said.

He cited Beijing’s “trashing” of the Sino-British Joint Declaration — the treaty supposed to guarantee Hong Kong a high degree of autonomy when it reverted from British to Chinese rule — and aggressive posturing in the South China Sea as areas of concern.

“This is not a country that is in any way managing itself to be a good and decent partner in anything at the moment. That’s why we need to review our relationship with them,” he added. “Those who think this is a case of separating trade from government — you can’t do that, that’s naive.”

Duncan Smith has lobbied other Conservative lawmakers to cut Huawei out from Britain’s new 5G network. Not only that: He says all existing Huawei technology in the UK telecoms infrastructure also needs to be eliminated as soon as possible.

The company has been at the center of tensions between China and Britain, as UK officials review how the latest US sanctions — imposed over allegations of cyberspying and aimed at cutting off Huawei’s access to advance microchips made with US technology — would affect British telecom networks.

Johnson in January decided that Huawei can be deployed in future 5G networks as long as its share of the market is limited. However, Johnson, his senior ministers and security chiefs yesterday decided to ban telecoms from buying 5G equipment from the Chinese firm.

Huawei says it is merely caught in the middle of a US-China battle over trade and technology. It has consistently denied allegations it could carry out cyberespionage or electronic sabotage at the behest of the Chinese Communist Party.

“We’ve definitely been pushed into the geopolitical competition,” Chinese Vice President Victor Zhang (張國威) said on Wednesday last week.

US accusations about security risks are all politically motivated, he added.

Nigel Inkster, senior adviser to the International Institute for Strategic Studies and former director of operations and intelligence at Britain’s MI6 intelligence service, said the issue with Huawei was not so much about immediate security threats.

Rather, the deeper worry lies in the geopolitical implications of China becoming the world’s dominant player in 5G technology, he said.

“It’s less about cyberespionage than generally conceived because, after all, that’s happening in any place,” he said. “This was never something of which the UK was lacking awareness.”

Still, Inkster said he has been cautioning for years that Britain needed a more coherent strategy toward China that balances the economic and security factors.

“There was a high degree of complacency” back in the 2000s, he said. “There was always less to the ‘golden era’ than met the eye.”

Britain rolled out the red carpet for Xi’s state visit in 2015, with golden carriages and a lavish banquet at Buckingham Palace with Queen Elizabeth II. A cybersecurity cooperation deal was struck, along with billions in trade and investment projects — including Chinese state investment in a British nuclear power station.

Cameron spoke about his ambitions for Britain to become China’s “best partner in the West.”

Enthusiasm has since cooled significantly.

The English city of Sheffield, which was promised a £1 billion (US$1.25 billion) deal with a Chinese manufacturing firm in 2016, said the investment never materialized.

Critics have called it a vanity project and a “candy floss deal.”

Economic and political grumbles about China erupted into sharp rebukes earlier this month, when Beijing imposed sweeping new national security laws on Hong Kong. Johnson’s government accused China of a serious breach of the Sino-British Joint Declaration, and announced it would open a special route to citizenship for up to 3 million eligible Hong Kong residents.

That amounts to “gross interference,” Chinese Ambassador to the UK Liu Xiaoming (劉曉明) said.

Liu also warned that a decision to get rid of Huawei could drive away other Chinese investment in the UK and derided Britain for succumbing to US pressure over the company.

Rana Mitter, an Oxford history professor specializing in China, said that the National Security Law — combined with broader resentment about Chinese officials’ handling of information about COVID-19 — helped set the stage for a perfect storm of wariness among Britain’s politicians and the public.

Mitter added that Britain has careened from “uncritically accepting everything about China” to a confrontational approach partly because of a lack of understanding about how China operates.

Some have cautioned against escalating tensions.

Former UK chancellor of the exchequer Philip Hammond said that weakening links with the world’s second-largest economy was particularly unwise at a time when Britain is severing trade ties with Europe and seeking partners elsewhere.

Hammond added that he was concerned about an “alarming” rise of anti-Chinese sentiment within his Conservative Party.

Duncan Smith rejected that, saying concerns about China’s rise are cross-party and multinational.

He is part of the Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China, a newly launched group of lawmakers from more than a dozen countries — from the US to Australia to Japan — that want a coordinated international response to the Chinese challenge.

“We need to recognize that this isn’t something one country can deal with,” he said.

Could Asia be on the verge of a new wave of nuclear proliferation? A look back at the early history of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), which recently celebrated its 75th anniversary, illuminates some reasons for concern in the Indo-Pacific today. US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin recently described NATO as “the most powerful and successful alliance in history,” but the organization’s early years were not without challenges. At its inception, the signing of the North Atlantic Treaty marked a sea change in American strategic thinking. The United States had been intent on withdrawing from Europe in the years following

My wife and I spent the week in the interior of Taiwan where Shuyuan spent her childhood. In that town there is a street that functions as an open farmer’s market. Walk along that street, as Shuyuan did yesterday, and it is next to impossible to come home empty-handed. Some mangoes that looked vaguely like others we had seen around here ended up on our table. Shuyuan told how she had bought them from a little old farmer woman from the countryside who said the mangoes were from a very old tree she had on her property. The big surprise

The issue of China’s overcapacity has drawn greater global attention recently, with US Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen urging Beijing to address its excess production in key industries during her visit to China last week. Meanwhile in Brussels, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen last week said that Europe must have a tough talk with China on its perceived overcapacity and unfair trade practices. The remarks by Yellen and Von der Leyen come as China’s economy is undergoing a painful transition. Beijing is trying to steer the world’s second-largest economy out of a COVID-19 slump, the property crisis and

Former president Ma Ying-jeou’s (馬英九) trip to China provides a pertinent reminder of why Taiwanese protested so vociferously against attempts to force through the cross-strait service trade agreement in 2014 and why, since Ma’s presidential election win in 2012, they have not voted in another Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) candidate. While the nation narrowly avoided tragedy — the treaty would have put Taiwan on the path toward the demobilization of its democracy, which Courtney Donovan Smith wrote about in the Taipei Times in “With the Sunflower movement Taiwan dodged a bullet” — Ma’s political swansong in China, which included fawning dithyrambs