The new COVID-19 coronavirus has spread to more than 100 countries — bringing social disruption, economic damage, sickness and death — largely because authorities in China, where it emerged, initially suppressed information about it. Yet China is now acting as if its decision not to limit exports of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and medical supplies — of which it is the dominant global supplier — was a principled and generous act worthy of the world’s gratitude.

When the first clinical evidence of a deadly new virus emerged in Wuhan, Chinese authorities failed to warn the public for weeks, and harassed, reprimanded and detained those who did.

This approach is no surprise: China has a long history of “killing” the messenger. Its leaders covered up SARS, another coronavirus, for more than a month after it emerged in 2002, and held the doctor who blew the whistle in military custody for 45 days. SARS ultimately affected more than 8,000 people in 26 countries.

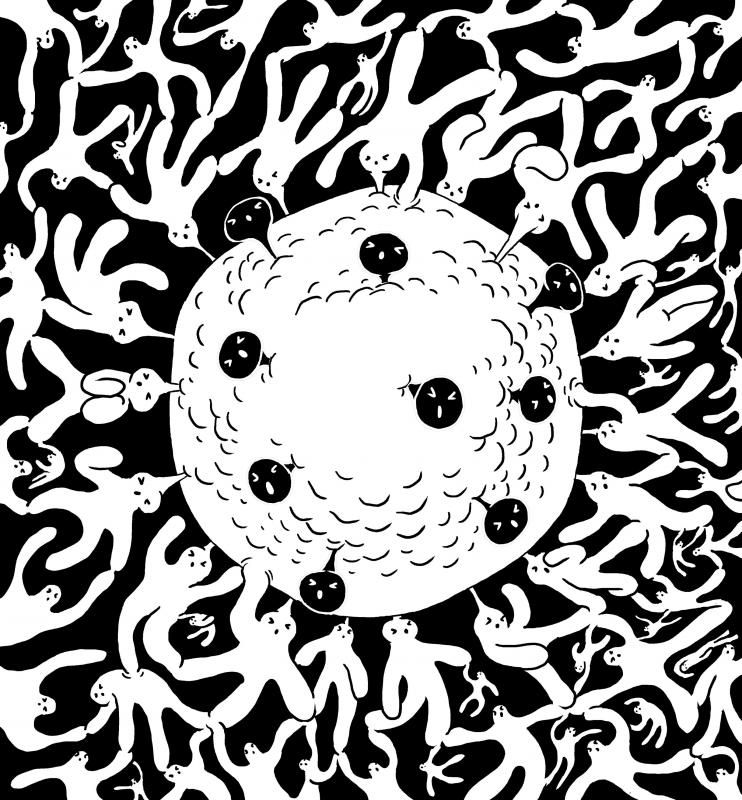

Illustration: Mountain People

This time around, the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) proclivity for secrecy was reinforced by Chinese President Xi Jinping’s (習近平) eagerness to be perceived as an in-control strongman, backed by a fortified CCP.

However, as with the SARS epidemic, China’s leaders could keep it under wraps for only so long. Once Wuhan-linked COVID-19 cases were detected in Thailand and South Korea, they had little choice but to acknowledge the epidemic.

About two weeks after Xi rejected scientists’ recommendation to declare a state of emergency, the government announced heavy-handed containment measures, including putting millions in lockdown.

However, it was too late: Many thousands of Chinese were already infected with COVID-19 and the virus was rapidly spreading internationally.

US National Security Adviser Robert O’Brien has said that China’s initial cover-up “probably cost the world community two months to respond,” exacerbating the global outbreak.

Beyond the escalating global health emergency, which has already killed thousands, the pandemic has disrupted normal trade and travel, forced many school closures, roiled the international financial system and sunk global stock markets. With oil prices plunging, a global recession appears imminent.

None of this would have happened had China responded quickly to evidence of the deadly new virus by warning the public and implementing containment measures. Indeed, Taiwan and Vietnam have shown the difference a proactive response can make.

Taiwan, learning from its experience with SARS, instituted preventive measures, including flight inspections, before China’s leaders had even acknowledged the outbreak. Likewise, Vietnam quickly halted flights from China and closed all schools. Both responses recognized the need for transparency, including updates on the number and location of infections, and public advisories on how to guard against COVID-19.

Thanks to their governments’ policies, both Taiwan and Vietnam — which normally receive huge numbers of travelers from China daily — have kept total cases relatively low. Neighbors that were slower to implement similar measures, such as Japan and South Korea, have been hit much harder.

If any other country had triggered such a far-reaching, deadly and above all preventable crisis, it would now be a global pariah.

However, China, with its tremendous economic clout, has largely escaped censure. Nonetheless, it would take considerable effort for Xi’s regime to restore its standing at home and abroad.

Perhaps that is why China’s leaders are publicly congratulating themselves for not limiting exports of medical supplies and APIs used to make medicines, vitamins and vaccines. If China decided to ban such exports to the US, Xinhua news agency has said, the US would be “plunged into a mighty sea of coronavirus.”

China, the article implied, would be justified in taking such a step. It would simply be retaliating against “unkind” US measures taken after COVID-19’s emergence, such as restricting entry to the US by Chinese and foreigners who had visited China. Isn’t the world lucky that China is not that petty?

Maybe so.

However, that is no reason to trust that China will not be petty in the future. After all, China’s leaders have a record of halting other strategic exports (such as rare-earth minerals) to punish countries that defied them.

Moreover, this is not the first time China has considered weaponizing its dominance in global medical supplies and APIs.

Last year, Li Daokui (李稻葵), a prominent Chinese economist, suggested curtailing Chinese API exports to the US as a countermeasure in the trade dispute.

“Once the export is reduced, the medical systems of some developed countries will not work,” Li said.

That is no exaggeration. A US Department of Commerce study found that 97 percent of all antibiotics sold in the US come from China.

“If you’re the Chinese and you want to really just destroy us, just stop sending us antibiotics,” Gary Cohn, former chief economic adviser to US President Donald Trump, said last year.

If the specter of China exploiting its pharmaceutical clout for strategic ends were not enough to make the world rethink its cost-cutting outsourcing decisions, the unintended disruption of global supply chains by COVID-19 should be.

China has had no choice but to fall behind in producing and exporting APIs since the outbreak — a development that has constrained global supply and driven up the prices of vital medicines.

That has already forced India, the world’s leading supplier of generic drugs, to restrict its own exports of some commonly used medicines. Almost 70 percent of the APIs for medicines made in India come from China. If China’s pharmaceutical plants do not return to full capacity soon, severe global medicine shortages would become likely.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the costs of Xi’s increasing authoritarianism. It should be a wake-up call for political and business leaders who have accepted China’s lengthening shadow over global supply chains for far too long. Only by loosening China’s grip on global supply networks — beginning with the pharmaceutical sector — can the world be kept safe from the country’s political pathologies.

Brahma Chellaney is a professor of strategic studies at the New Delhi-based Center for Policy Research and a fellow at the Robert Bosch Academy in Berlin.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

Recently, China launched another diplomatic offensive against Taiwan, improperly linking its “one China principle” with UN General Assembly Resolution 2758 to constrain Taiwan’s diplomatic space. After Taiwan’s presidential election on Jan. 13, China persuaded Nauru to sever diplomatic ties with Taiwan. Nauru cited Resolution 2758 in its declaration of the diplomatic break. Subsequently, during the WHO Executive Board meeting that month, Beijing rallied countries including Venezuela, Zimbabwe, Belarus, Egypt, Nicaragua, Sri Lanka, Laos, Russia, Syria and Pakistan to reiterate the “one China principle” in their statements, and assert that “Resolution 2758 has settled the status of Taiwan” to hinder Taiwan’s

The past few months have seen tremendous strides in India’s journey to develop a vibrant semiconductor and electronics ecosystem. The nation’s established prowess in information technology (IT) has earned it much-needed revenue and prestige across the globe. Now, through the convergence of engineering talent, supportive government policies, an expanding market and technologically adaptive entrepreneurship, India is striving to become part of global electronics and semiconductor supply chains. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Vision of “Make in India” and “Design in India” has been the guiding force behind the government’s incentive schemes that span skilling, design, fabrication, assembly, testing and packaging, and

Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong’s (李顯龍) decision to step down after 19 years and hand power to his deputy, Lawrence Wong (黃循財), on May 15 was expected — though, perhaps, not so soon. Most political analysts had been eyeing an end-of-year handover, to ensure more time for Wong to study and shadow the role, ahead of general elections that must be called by November next year. Wong — who is currently both deputy prime minister and minister of finance — would need a combination of fresh ideas, wisdom and experience as he writes the nation’s next chapter. The world that

As former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) wrapped up his visit to the People’s Republic of China, he received his share of attention. Certainly, the trip must be seen within the full context of Ma’s life, that is, his eight-year presidency, the Sunflower movement and his failed Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement, as well as his eight years as Taipei mayor with its posturing, accusations of money laundering, and ups and downs. Through all that, basic questions stand out: “What drives Ma? What is his end game?” Having observed and commented on Ma for decades, it is all ironically reminiscent of former US president Harry