Walking proudly down a catwalk, the lights and glamor seemed like a lifetime away from Elzat Kazakbaeva’s nightmare ordeal five years ago when she was grabbed off a Kyrgyzstan street by a group of men wanting to marry her to an uninvited suitor.

Kazakbaeva is one of thousands of woman abducted and forced to marry each year in the former Soviet republic in Central Asia, where bride kidnappings continue, particularly in rural areas.

Bride kidnapping — which also occurs in nations like Armenia, Ethiopia and Kazakhstan — was outlawed in 2013 in Kyrgyzstan, where authorities recognized that it could lead to marital rape, domestic violence and psychological trauma.

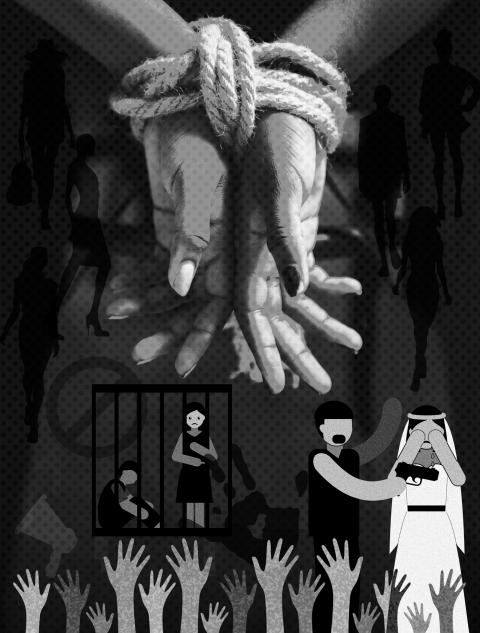

Illustration: Louise Ting

However, some communities still see it as a pre-Soviet tradition dating back to tribal prestige, said Russell Kleinbach, professor emeritus of sociology at Philadelphia University and cofounder of women’s advocacy group Kyz Korgon Institute.

Now a new generation of women are eschewing acceptance of this abuse, with their campaign escalating last year when one kidnapped bride, Burulai Turdaaly Kyzy, 20, was put in the same police cell as the man who abducted her and stabbed to death.

Her killer was jailed for 20 years, but her murder sparked national outrage and protests against bride kidnappings in a country where campaigners said that until recently, tougher sentences were handed down for kidnapping livestock than women.

Fashion designer Zamira Moldosheva is part a rising public movement against bride kidnapping that has ranged from charity bike rides to flag installations, with campaigners saying more events would be planned this year.

She organized a fashion show featuring only women who had been abused or kidnapped dressed as historical Kyrgyz women.

“Can’t we women do something against the violence taking place in our country?” Moldosheva said in an interview in Bishkek, the capital of the majority-Muslim nation of 6 million people.

“Bride kidnapping is not our tradition — it should be stopped,” she said, adding that bride kidnapping was a form of forced marriage and not a traditional practice.

Kazakbaeva, one of 12 models in the fashion show, said she was glad to participate in the event in October last year to highlight her ordeal and encourage other women to flee forced marriages.

Kazakbaeva, then a student aged 19, was ambushed in broad daylight on a Saturday afternoon outside her college dormitory in Bishkek and forced into a waiting car by a group of men.

“I felt as if I was an animal,” Kazakbaeva told reporters, her faced streaked with tears. “I couldn’t move or do anything at all.”

Kazakbaeva was taken to the groom’s home in rural Issyk Kul region, about 200km east of Bishkek, where she was dressed in white and taken into a decorated room for an impending ceremony.

She spent hours pleading with the groom’s family — and her own — to stop the forced marriage.

“My grandmother is very traditional, she thought it would be a shame and she started convincing me to stay,” Kazakbaeva said.

When her mother threatened to call the police, the groom’s family finally let her go.

She was lucky to escape unwed, she said, and hoped the fashion show, depicting historical female figures, would help to bring the taboo subject to the fore.

“Women nowadays can also be the characters of new fairy tales for others,” said Kazakbaeva, dressed as a female freedom fighter from ancient Kyrgyzstan, which gained independence from Moscow in 1991. “I’m fighting for women’s rights.”

Kyrgyzstan toughened laws against bride kidnapping in 2013, making it punishable by up to 10 years in prison, according to the UN Development Program, which said it was a “myth” that the practice was ever part of the culture.

In a handful of cases the kidnappings are consensual, said Kleinbach, especially in poorer communities where the practice was akin to eloping to save costs of a ceremony or hefty dowry.

A UN Development Program spokeswoman said data were scant on the number of women abducted each year, as many women did not report the crime through fear, but they estimated that about 14 percent of women aged under 24 are still married through some form of coercion.

“They don’t want to report, this is the issue,” Umutai Dauletova, gender coordinator at the UN Development Program in Kyrgyzstan, told reporters.

Dauletova said most cases did not make it to court, as women retracted their statements, often under pressure from female family members, fearing public shaming for disobedience or no longer being a virgin.

“This is the phenomenon of women suppressing other women,” she said.

Aida Sooronbaeva, 35, was not as fortunate as Kazakbaeva.

Back from school, aged 17, she found her grandfather tied up and her home smashed up, so she hid until her brother tricked her to seek refuge with a friend, whose family kidnapped her.

Initially she refused to marry their son and tried to escape, but she said she was eventually worn down by social pressure in her village and was married for 16 years, despite domestic abuse.

“He kept me at home, never letting me out, just in the yard,” said Sooronbaeva, exposing scars on her neck and stomach. “I lived with him only for the sake of my children.”

A few years ago, the violence got so bad that she ran into the street where she was rescued by a passer-by and she finally plucked up the courage to leave her husband.

She said she hoped that speaking out, and taking part in campaigns like the fashion show, would break the taboos surrounding forced marriage.

“Now I perceive any man as an enemy. I never even think of getting remarried,” said Sooronbaeva, adorned in heavy jewelery and colorful make-up.

However, she added, with a note of optimism: “Women are strong, we can survive.”

The Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, covers humanitarian news, women’s rights, trafficking, property rights, climate change and resilience.

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were born under the sign of Gemini. Geminis are known for their intelligence, creativity, adaptability and flexibility. It is unlikely, then, that the trade conflict between the US and China would escalate into a catastrophic collision. It is more probable that both sides would seek a way to de-escalate, paving the way for a Trump-Xi summit that allows the global economy some breathing room. Practically speaking, China and the US have vulnerabilities, and a prolonged trade war would be damaging for both. In the US, the electoral system means that public opinion

They did it again. For the whole world to see: an image of a Taiwan flag crushed by an industrial press, and the horrifying warning that “it’s closer than you think.” All with the seal of authenticity that only a reputable international media outlet can give. The Economist turned what looks like a pastiche of a poster for a grim horror movie into a truth everyone can digest, accept, and use to support exactly the opinion China wants you to have: It is over and done, Taiwan is doomed. Four years after inaccurately naming Taiwan the most dangerous place on

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

Wherever one looks, the United States is ceding ground to China. From foreign aid to foreign trade, and from reorganizations to organizational guidance, the Trump administration has embarked on a stunning effort to hobble itself in grappling with what his own secretary of state calls “the most potent and dangerous near-peer adversary this nation has ever confronted.” The problems start at the Department of State. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has asserted that “it’s not normal for the world to simply have a unipolar power” and that the world has returned to multipolarity, with “multi-great powers in different parts of the