Five hundred tonnes of Christmas tree lights and at least 25 million bags of plastic sweet wrappers, turkey coverings, drinks bottles and broken toys were thrown away by UK homes at Christmas and New Year. However, only a tiny proportion of this festive plastic waste will be recycled.

Even at more typical times of year, only a little under one-quarter of the UK’s plastic waste is recycled, but over the festive period still less escapes the tip, according to survey by home drinks makers SodaStream. Globally, recycling of plastics is even smaller.

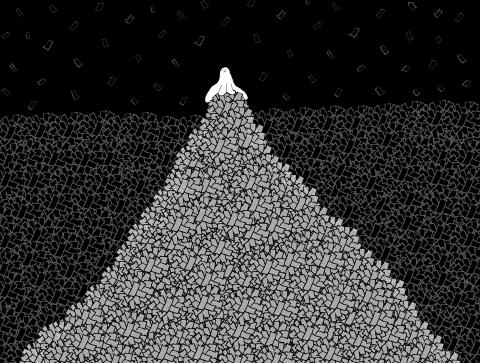

The outcome is a belief that planet Earth is being slowly strangled by a gaudy coat of impermeable plastic waste that collects in great floating islands in the world’s oceans; clogs up canals and rivers; and is swallowed by animals, birds and sea creatures. In many parts of the developing world it acts as a near ubiquitous outdoor decoration, along roads in India, around villages in Africa and fluttering off fences across Latin America. And when it is not piling up, it is often burned in the open, releasing noxious smoke into the surrounding area.

From the central parks of Moscow after the spring thaw, strewn with plastic uncovered by the melting snows, to some of the most remote places on Earth — the summit of Mount Everest or the Tibetan Plateau — nowhere, it seems, is free of discarded bags, bottles, unwanted toys, used toothbrushes and lost beach shoes.

There are no global figures on the true scale of the problem, but according to the European Packaging and Films Association (PAFA) 265 million tonnes of plastic are produced globally each year. In the UK at least, about two-thirds of this is for packaging, which globally would translate to 170 million tonnes of plastic largely created to be disposed after one use. Even at the almost unmatched EU recycling rate averaging 33 percent, two-thirds of that, or more than 113 million tonnes, would end up in landfill, being burned, or cluttering up the environment that people and wildlife live in.

Such a figure — almost certainly a huge underestimate, and excluding more “permanent” items from car parts to Barbie dolls — would be more than enough to cover the 48 contiguous states of the US in plastic food wrapping. If the world recycled packaging at the rate the US does, 15 percent, it would generate more than enough plastic to cover China in plastic wrap. Every year.

A few years ago the UK was seized by worry about plastic bags: communities went “plastic-bag free,” and then-British prime minister Gordon Brown announced he would talk to major retailers about phasing out their use. In the absence of much change, his successor as prime minister, David Cameron, recently re-raised the idea of a national levy.

In response, the plastics industry argues that the alternatives would be even more wasteful in terms of extra greenhouse gas emissions.

What would this world without plastic look like? Earlier this year Austrian-based environmental consultancy Denkstatt imagined such a world, where farmers, retailers and consumers use wood, metal tins, glass bottles and jars, and cardboard to cover their goods. It found the mass of packaging would increase by 3.6 times, it would take more than double the energy to make, and the greenhouse gases generated would be 2.7 times higher.

To understand this, consider the properties of plastic that make it so attractive to use: it is durable, it is flexible and does not shatter, it can breathe — or not, and it is extremely lightweight. As a result, food and drink are protected from damage and kept for lengths of time previously unimaginable. The PAFA says average spoilage of food between harvest and table is 3 percent in the developed world, compared with 50 percent in developing countries where plastic palates, crates, trays, film and bags are not so prolific. Once the food reaches people’s homes its lifespan is also increased — in the case of a shrink-wrapped cucumber from two to 14 days. A less obvious benefit of plastic packaging is that by being much lighter than alternatives it greatly reduces the fuel needed to transport the goods. Because of the huge carbon content of our diets, it is estimated that for every tonne of carbon produced by making plastic, five tonnes is saved, says Barry Turner from the PAFA.

A more surprising point is made by Friends of the Earth’s waste campaigner Julian Kirby, who points out that because it is inert in landfill, plastic waste buried in the ground is a counterintuitive way of “sequestering” carbon and so avoiding it adding to global warming and climate change.

However, this focus on carbon and climate change ignores the very reasons plastic bags, and plastic packaging generally, first gripped the public imagination — namely that it is such a highly visible result of our throw-away society.

Wales, Ireland and other countries have opted to levy a tax on plastic bags to deter their use, but making deeper cuts to plastic waste will need other options too.

Many “ethical” products from sandwiches to nappy bags have switched to biodegradable plastics, made either from natural products such as cornstarch or by using a special additive which helps breakdown the plastic. However, Turner suggests this will remain a niche, because the process is expensive and — in his words — is “destroying” a resource that could be recycled.

Recycling plastic is particularly hard, because there are so many types, and because plastic melts below the boiling point of water, making it hard to remove contamination. Increasing recycling is, though, one of the two key areas focused on by the plastics industry, which estimates if every council in the UK operated at the rates achieved by the best local authority for each type of plastic — PET bottles, cartons, trays, bags and so on — the country could raise total plastic recycling from 23 percent to 45 percent.

“On the go recycling” — currently almost non-existent — also needs to be dramatically improved by things like separated waste bins, or simply more bins in public places, Turner said.

To meet the industry’s self-imposed target of zero plastic waste to landfill by 2020, however, it is largely looking to incineration, which is highly controversial with environment groups and local communities who worry about how waste ash is disposed of and breathing in emissions from the plants — despite the Health Protection Agency giving modern plants the go ahead as not damaging to health.

Greenhouse gas emissions from such plants are also high: equivalent to 540g of carbon dioxide per kilowatt hour, more than gas power and more than 100 times that for nuclear.

Instead, environment and wildlife campaigners want far more attention to the “waste hierarchy” — reduce, reuse, recycle. To drive this change, the UK government last month proposed increasing all recycling targets, raising plastics to 50 percent. If enforced, that should encourage innovations, such as more food recycling (which research suggests reduces over-purchasing and so the need for packaging), and the recent development of a new dye for black plastic bags which, unlike the traditional compound, can be detected by the automatic sorting machines.

Further afield, 47 industry groups from around the world have joined forces to fund research and schemes to stop plastic from getting into the seas and oceans. While on land, countries without plastic recovery regulations could adopt a system used in several European countries like Belgium, where manufacturers are responsible for recovering a percentage of the plastic they produce.

“The idea of producer responsibility is one of the ones people are most agreed on, but no-one’s sure how,” Kirby said.

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were born under the sign of Gemini. Geminis are known for their intelligence, creativity, adaptability and flexibility. It is unlikely, then, that the trade conflict between the US and China would escalate into a catastrophic collision. It is more probable that both sides would seek a way to de-escalate, paving the way for a Trump-Xi summit that allows the global economy some breathing room. Practically speaking, China and the US have vulnerabilities, and a prolonged trade war would be damaging for both. In the US, the electoral system means that public opinion

They did it again. For the whole world to see: an image of a Taiwan flag crushed by an industrial press, and the horrifying warning that “it’s closer than you think.” All with the seal of authenticity that only a reputable international media outlet can give. The Economist turned what looks like a pastiche of a poster for a grim horror movie into a truth everyone can digest, accept, and use to support exactly the opinion China wants you to have: It is over and done, Taiwan is doomed. Four years after inaccurately naming Taiwan the most dangerous place on

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

Wherever one looks, the United States is ceding ground to China. From foreign aid to foreign trade, and from reorganizations to organizational guidance, the Trump administration has embarked on a stunning effort to hobble itself in grappling with what his own secretary of state calls “the most potent and dangerous near-peer adversary this nation has ever confronted.” The problems start at the Department of State. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has asserted that “it’s not normal for the world to simply have a unipolar power” and that the world has returned to multipolarity, with “multi-great powers in different parts of the