The dance around the golden Nobel medallion began more than 100 years ago and is still going strong. As icon, myth and ritual, the Nobel Prize is well secured. But what do we actually know about the Nobel Prize?

Shrouded in secrecy and legend, the Nobel Prize first became an object for serious scholarly study after 1976, when the Nobel Foundation opened its archives. Subsequent research by historians of science leaves little doubt: The Nobel medallion is etched with human frailties.

Although many observers accept a degree of subjectivity in the literature and peace prizes, the science prizes have long been assumed to be an objective measure of excellence.

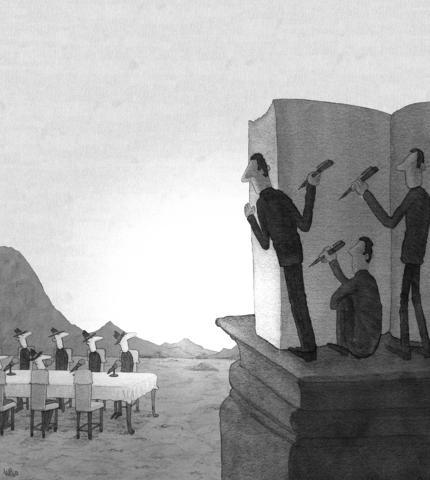

But, from the start, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, which awards the physics and chemistry prizes, and the Caroline Institute, which awards those for medicine/physiology, have based their decisions on the recommendations of their respective committees. And the committee members' own understanding of science has been critical in determining outcomes.

From the beginning, the inner world of those entrusted to make recommendations was marked by personal and principled discord over how to interpret Alfred Nobel's cryptic will and to whom prizes should be awarded. While committee members tried to be dispassionate, their own judgment, predilections and interests necessarily entered into their work, and some championed their own agendas, whether openly or cunningly.

Winning a Nobel has never been an automatic process, a reward that comes for having attained a magical level of achievement. Designated nominators rarely provided committees with a clear consensus, and the committees often ignored the rare mandates when a single strongly nominated candidate did appear, such as Albert Einstein for his work on relativity theory. Academy physicists had no intention of recognizing this theoretical achievement "even if the whole world demands it." The prize is a Swedish prerogative.

Moreover, a simple change in the composition of the committee could decide a candidate's fate. Not until committee strongman C. W. Oseen died in 1944 could the theoretical physicist Wolfgang Pauli -- one of the giants of quantum mechanics -- receive a prize.

Conversely, the Academy of Sciences sometimes rebelled against its committees. Harboring a grudge, one chemist rallied the academy to block the committee's recommendation for the Russian Dmitry Mendeleyev, who created the periodic table.

Even when all involved tried to rise above pettiness and partiality, selecting winners was always difficult -- and remains so. Committee members occasionally confessed privately that often several candidates could be found who equally deserved a prize. Unambiguous, impartial criteria for selecting a winner were not at hand -- and never will be.

The confused situation faced by the Caroline Institute in 1950 reminds us that all prize committees face difficult choices: After four indecisive rounds of preliminary voting, three primary alternatives emerged, but the outcome was still uncertain. When urging a colleague to come to the meeting, one committee member noted that if somebody were to catch cold, a completely different decision might be reached.

The image of science advancing through the efforts of individual genius is, of course, appealing. Yet, to a greater extent than the prizes allow, research progresses through the work of many.

Brilliant minds do matter, but it is often inappropriate and unjust to limit recognition to so few, when so many extremely talented scientists may have contributed to a given breakthrough. The Nobel bylaws do not allow splitting a prize into more than three parts, thereby excluding discoveries that entailed work by more than three researchers, or omitting key persons who equally deserved to share in the honor.

It has also become clear that many important branches of science are not addressed by Alfred Nobel's testament (limited to physics, chemistry, physiology/medicine). Some of the past century's greatest intellectual triumphs, such as those related to the expanding universe and continental drift, have not been celebrated. Environmental sciences -- surely of fundamental importance -- also come up empty. There is nothing wrong with wanting heroes, but we should understand the criteria used to select those whom we are asked to revere.

Why do people venerate the Nobel Prize? There is no easy answer. The cult of the Nobel began even before the first winners were announced. Media fascination whipped up speculation and interest. The creed of the Nobel did not depend so much on the merit of the winners, as much as the understanding that the Nobel was a powerful means to gain prestige, publicity, and advantage.

Even scientists who frowned upon the committees' limitations and sometimes odd choices nevertheless still nominated and lobbied for candidates, knowing that if successful, a winner can draw attention and money to a research specialty, institution, or scientific community.

Is science or society well served by a fixation on prizes and on nurturing a culture of extreme competition? Perhaps once the mystery of the Nobel Prize is reduced, we might reflect on what is truly significant in science. The soul and heritage of science going back several centuries is far richer than the quest for prizes.

Robert Friedman, professor of the history of science at the University of Oslo, is the author of The Politics of Excellence: Behind the Nobel Prize in Science.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

China has not been a top-tier issue for much of the second Trump administration. Instead, Trump has focused considerable energy on Ukraine, Israel, Iran, and defending America’s borders. At home, Trump has been busy passing an overhaul to America’s tax system, deporting unlawful immigrants, and targeting his political enemies. More recently, he has been consumed by the fallout of a political scandal involving his past relationship with a disgraced sex offender. When the administration has focused on China, there has not been a consistent throughline in its approach or its public statements. This lack of overarching narrative likely reflects a combination

US President Donald Trump’s alleged request that Taiwanese President William Lai (賴清德) not stop in New York while traveling to three of Taiwan’s diplomatic allies, after his administration also rescheduled a visit to Washington by the minister of national defense, sets an unwise precedent and risks locking the US into a trajectory of either direct conflict with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) or capitulation to it over Taiwan. Taiwanese authorities have said that no plans to request a stopover in the US had been submitted to Washington, but Trump shared a direct call with Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平)

Heavy rains over the past week have overwhelmed southern and central Taiwan, with flooding, landslides, road closures, damage to property and the evacuations of thousands of people. Schools and offices were closed in some areas due to the deluge throughout the week. The heavy downpours brought by the southwest monsoon are a second blow to a region still recovering from last month’s Typhoon Danas. Strong winds and significant rain from the storm inflicted more than NT$2.6 billion (US$86.6 million) in agricultural losses, and damaged more than 23,000 roofs and a record high of nearly 2,500 utility poles, causing power outages. As

The greatest pressure Taiwan has faced in negotiations stems from its continuously growing trade surplus with the US. Taiwan’s trade surplus with the US reached an unprecedented high last year, surging by 54.6 percent from the previous year and placing it among the top six countries with which the US has a trade deficit. The figures became Washington’s primary reason for adopting its firm stance and demanding substantial concessions from Taipei, which put Taiwan at somewhat of a disadvantage at the negotiating table. Taiwan’s most crucial bargaining chip is undoubtedly its key position in the global semiconductor supply chain, which led