Mao Zedong (

China is in the midst of a guerrilla war, a conflict against the world's biggest censor that is very much in keeping with the information age. In the 1940s, Mao's communist rebels used hit-and-run tactics to sap the morale -- and eventually defeat -- the numerically superior but morally bankrupt Nationalist forces. This time, it is journalists, bloggers and dissidents who are probing the defenses of a more powerful but equally despised enemy: the propaganda department of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Media battles are nothing new in China, where the best journalists have been quietly pushing at the boundaries of free speech for more than 20 years. But the past week has seen a very public and international escalation of hostilities.

After the sacking of three leading editors and the closure of Freezing Point -- a respected publication -- some of the country's most influential liberals have joined forces and fought back, using new technology and a rediscovered boldness not seen since the late 1980s.

The fired editor of Freezing Point, Li Datong (

Fighting back rather than accepting punishment is unusual, but not unprecedented. What has been astonishing -- and what should alarm the authorities the most -- is where their support has come from.

In a joint letter, 13 retired officials, academics and lawyers -- including Li Rui (

"History demonstrates that only a totalitarian system needs news censorship, out of the delusion that it can keep the public locked in ignorance," they wrote. "Depriving the public of freedom of expression so nobody dares speak out will sow the seeds of disaster for political and social transition."

The signatories were a who's who of liberal elders, many of whom dictated media policy during the flowering of free expression in the 1980s. They included Zhu Houze (

This old guard declared the closure of Freezing Point a "major historic incident," a claim that was sharpened by the background -- widespread discontent with the CCP; and the timing -- the same week that the US Congress took Google, Yahoo and Microsoft to task for collaborating with the censors in Beijing.

But the real force for change is technology rather than politics, as the censors are the first to admit.

"The Internet is now the main influence on public opinion," a government official responsible for Internet surveillance said. "The people who get their information from the Web are the most active sector of society -- 80 percent of Web users are under 35. So our government pays more and more attention to the Internet because it is so important."

That attention does not appear to be paying off.

"On the bulletin boards, most of the comment about the party is negative," the official admitted. "We need to work on that. We cannot ignore public opinion, especially when it is allied to technological change."

At first sight, China's online population of 111 million seems studiously apolitical. Most just chat, play games, download music and watch porn, like everywhere in the world. Very few would consider themselves interested in politics, which has become something of an old-fashioned word, let alone democratic activism.

Yet there is lively debate on the Internet that is largely critical of the CCP, which is blamed for corruption, injustice and restrictions on the Web.

Print journalists are among the most active and the most influential voices on the Web, which they use to publish what the censors block from newspapers and magazines. Many were furious about the closure of Freezing Point, but their frustrations -- and ambitions for change -- stretch back far further.

"There is a big change in attitude among journalists," said one former editor, who asked to remain nameless. "The Communist Party always claimed to be on the side of the public, but most journalists and editors no longer believe this. They want to write reports that reform society, that hold the authorities to account. This is now mainstream thinking. It wasn't 10 years ago."

Another editor, who -- like many of the reformers -- was a student during the 1989 Tiananmen protests, agrees.

"I think our generation may be a revolutionary one. Not in the old sense, but in the way we embrace change, very rapid change. We want more democracy," the editor said.

Many had hoped for a loosening of controls when Hu Jintao (

It did not last.

We have learned that former president Jiang Zemin (

New filtering software has been introduced to limit access to "spiritually impure" information, which includes positive references to the Dalai Lama, Taiwanese independence or the Falun Gong spiritual movement. An Internet police force -- reportedly numbering 30,000 -- trawls Web sites and chatrooms, deleting anti-Communist comments and posting pro-government messages.

Even foreign Internet giants have been press-ganged into the biggest censorship operation in history. In order to do business in China, Microsoft does not allow the word "democracy" to be used in a subject heading for its MSN Spaces blog service; Google last month restricted search results for the Tiananmen Square Massacre and Yahoo handed over private e-mail information that reportedly led to the conviction of two Internet dissidents.

Yet even with the sophisticated filtering software, the collaboration of Internet giants and the increasingly heavy-handed crackdowns on dissidents and journalists, the propaganda department appears to be losing the battle for hearts and minds.

It is partly because there are so many ways around the restrictions, including the use of proxy servers to reach blocked Web sites and the use of slang terms to discuss sensitive subjects in chatrooms.

It is partly because the volume of information available online is so huge that even an army of Internet police can not cover all of the billion-plus Web pages, 111 million users, more than 5 million blogs, countless bulletin boards, numerous languages and a vast smorgasbord of images. English results turn up far more sensitive information than those in Mandarin. Pictures of demonstrations -- which cannot easily be filtered by keyword -- are widely available.

But the main reason why the propaganda department is losing credibility is that its message has become even more out of date than its technology.

China is getting richer, but its 1.3 billion people are becoming more divided. Demonstrations -- usually sparked when corrupt officials seize land for development -- are now commonplace.

Even the central government appears to be struggling to rein in avaricious local leaders, who treat their territories like personal fiefdoms. For the past three years, many journalists feel they have been encouraged by Beijing to go out into the provinces and expose bribery, pollution and lax industrial safety because central government officials cannot otherwise get reliable information, let alone implement the law.

But every scandal tarnishes the party. The media may still be state-controlled, but that does not mean the journalists are on their side. The CCP is in trouble -- there are guerrillas in its midst -- and the crackdown suggests its leaders know it.

According to the Committee to Protect Journalists and Reporters Without Borders, 32 journalists and 81 Internet dissidents are in jail.

For the moment, the authorities still have the upper hand. But the past week has brought closer together some of the most powerful opinion-formers from China's future and its past: the angry young online and the retired old guard. The propaganda authorities are now wedged uncomfortably between the two.

Pressure is also building overseas, particularly in the US. At a congressional hearing last week, Yahoo, Microsoft, Cisco and Google were accused of sacrificing principles for profits in colluding with Beijing's censors.

Some Chinese bloggers believe the media furore surrounding them misses the point.

In his EastSouthWestNorth blog, Roland Soong wrote: "These are regarded as simply Western exercises in self-absorption, self-indulgence and self-flagellation, and completely alien to the Chinese situation."

Others strike a distinctly nationalist tone, saying Washington should mind its own business.

"The freedom and rights of the Chinese people can only be won by the Chinese people themselves," said Zhao Jing (趙京), who blogs under the pen name Michael Anti (安替).

"The only true way of solving the Internet blockage in China is this: Every Chinese youth with conscience must practice and expand their freedom and oppose any blockage and suppression every day. This is the country that we love ... Nobody wants her to be free more than we do," he said.

Whether because of young bloggers, old cadres or US congressmen, the Chinese authorities are -- at least temporarily -- on the defensive. As well as retired cadres joining forces, another previously unheard of event took place last week: a press conference by the normally secretive Internet Affairs Bureau of the State Council.

"No one in China has been arrested simply because he or she said something on the Internet," insisted Liu Zhengrong (

The propaganda office also announced that it will re-open Freezing Point, though with a new editor. A condition for the resumption is that the first edition must include self-criticism of the "mistakes" that led to the closure.

We could not reach Li Datong, the sacked editor, for comment. But he told Reuters that the re-opening was a sham.

"This exterminates the soul of Freezing Point, leaving an empty shell," he was quoted as saying.

He went on to say he was "extremely disappointed," but before he could explain, his telephone was abruptly cut off.

Muted voices

Shi Tao (

Yang Tongyan (楊同彥): He has been held without contact since last December on the grounds that the case involves "state secrets." He had previously spent 10 years in prison on "counter-revolution" charges for condemning the Tiananmen Square Massacre.

Huang Jingao (

Li Changqing (李長青): Sentenced to three years' imprisonment last month in connection with an article on the banned Boxun News Web site exposing an outbreak of dengue fever in Fujian Province before the authorities officially announced it.

Zhu Wanxiang (祝萬祥) and Wu Zhengyou (吳正有): Detained last August after reporting on land disputes and rural unrest in Zhejiang Province. Zhu was sentenced to 10 years, Wu to six year.

Ching Cheong (程翔): A correspondent for the Singapore-based daily the Straits Times, Ching was detained last April while seeking transcripts of interviews with ousted former Chinese leader Zhao Ziyang (

Zheng Yichun (程益中): Imprisoned in December 2004 after criticizing the Chinese Communist Party and China's political leaders in online publications, including the banned US-based dissident Web site Dajiyuan.

Zhao Yan (趙岩): The New York Times researcher faces 10 years in prison for "providing state secrets to foreigners." Zhao was detained in September 2004 after the Times printed an article correctly predicting the retirement of former president Jiang Zemin (江澤民) as chairman of the central military commission.

Zhang Lin (張林): A political essayist, who wrote regularly for overseas online news sites, he was sentenced to five years last July on allegations of inciting subversion.

Zheng Yichun (

Yu Huafeng (喻華峰) and Li Minying (李民英): The editor-in-chief and former editor of Nanfang Dushi Bao are serving eight years and six years in prison for corruption and bribery. In December 2003, their paper reported the first suspected SARS case in China since the epidemic died out in July that year.

Kong Youping (

Huang Jinqiu (

Luo Yongzhong (

Luo Changfu (

Cai Lujun (

Abdulghani Memetemin: Sentenced to nine years in 2003 on charges of "leaking state secrets."

Zhang Wei (

Tao Haidong (

Yang Zili (

Jiang Weiping (

Xu Zerong (

Wu Yilong (吳義龍), Mao Qingxiang (毛慶祥) and Zhu Yufu (朱虞夫): Sentenced to 25 years in 1999.

Gao Qinrong (

Hua Di (華棣): Charged with revealing state secrets. Serving a 10-year sentence.

Fan Yingshang (範穎尚): Serving a 15-year prison sentence.

Chen Renjie (陳人傑) and Lin Youping (林佑平): Chen was sentenced to life in 1983 and Lin was sentenced to death, later reprieved, for publishing a counter-revolutionary pamphlet.

Executed: Chen Biling (

Source: The Guardian and the Committee to Protect Journalists

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were born under the sign of Gemini. Geminis are known for their intelligence, creativity, adaptability and flexibility. It is unlikely, then, that the trade conflict between the US and China would escalate into a catastrophic collision. It is more probable that both sides would seek a way to de-escalate, paving the way for a Trump-Xi summit that allows the global economy some breathing room. Practically speaking, China and the US have vulnerabilities, and a prolonged trade war would be damaging for both. In the US, the electoral system means that public opinion

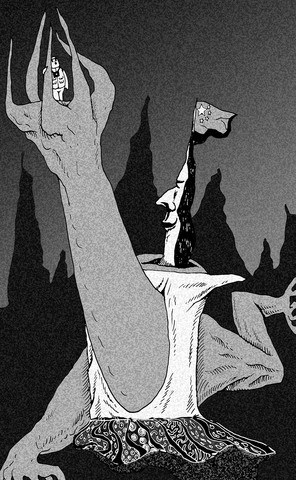

They did it again. For the whole world to see: an image of a Taiwan flag crushed by an industrial press, and the horrifying warning that “it’s closer than you think.” All with the seal of authenticity that only a reputable international media outlet can give. The Economist turned what looks like a pastiche of a poster for a grim horror movie into a truth everyone can digest, accept, and use to support exactly the opinion China wants you to have: It is over and done, Taiwan is doomed. Four years after inaccurately naming Taiwan the most dangerous place on

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

Wherever one looks, the United States is ceding ground to China. From foreign aid to foreign trade, and from reorganizations to organizational guidance, the Trump administration has embarked on a stunning effort to hobble itself in grappling with what his own secretary of state calls “the most potent and dangerous near-peer adversary this nation has ever confronted.” The problems start at the Department of State. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has asserted that “it’s not normal for the world to simply have a unipolar power” and that the world has returned to multipolarity, with “multi-great powers in different parts of the