When Shubham Saxena took his electricians course online during India’s COVID-19 lockdown, he spent the first few days teaching his class of mainly unskilled migrant workers how to use the mute button. They fast progressed to weightier matters.

Millions of migrant workers who lost their jobs during the country’s strict lockdown earlier this year have turned to online training courses like Saxena’s to learn new skills as they seek to re-enter the labor market, or start a business.

“The response is amazing and we encourage our students to set up their own shop,” said Saxena, 26, who uses an online platform created by start-ups Spayee and JustRojgar to teach.

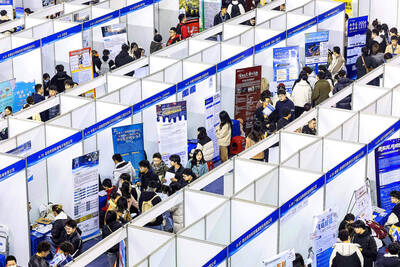

Photo: AP

“In fact, the lockdown has seen many workers become entrepreneurs, starting their own food stalls or vegetable carts and small businesses,” he said.

An estimated 100 million migrants, predominantly daily wage workers with no job security, were among the worst affected by tough lockdown restrictions between March and early June — their plight drawing global attention.

Considered the backbone of India’s urban economy, they poured out of cities where they had worked on building sites and factories, drove taxis or delivered takeouts. Some trekked hundreds of kilometers to reach their home villages.

Many are reluctant to return to the cities having gone without work, pay or financial assistance in the first three months of lockdown, labor right campaigners said.

Various state governments began mapping migrants for the first time this year, emphasizing the need for them to gain new skills and increase their chances of finding work nearer home.

The Indian government is also revamping its Skill India program, which aims to give skills training to 400 million people by 2022 to broaden their employment options.

It has launched an app aimed at workers, shifting focus to their needs rather than the skills requirements of businesses.

“We are launching a pilot project in January where district committees will be asked to identify what skills will help workers get better jobs,” Indian Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship Secretary Praveen Kumar said.

“The new app will be user-friendly, in multiple languages and help workers identify their aptitude. We are also customizing content for cheaper smartphones that workers use and are creating both practical and online training modules,” he said.

Ankit Kumar, 22, a student in Saxena’s electricians classes, sees the training program as a way to expand his options.

“Nearly 90 percent of my friends and people around our village lost their jobs during the lockdown,” Kumar told reporters from his home near Haridwar in northern Uttarakhand State.

“I dropped out of college and recently found a job in a private company. But I want to upskill, because this course will help me get a better job, maybe more money also. I may also work independently as an electrician. The options are more,” he said.

From access to recorded sessions to the promise of practical training and job placement, many skills programs are promising workers “dignified employment.”

“These courses give workers an opportunity to divert from hazardous or unproductive lifelong work to self-employment and dignified work,” said Sanjay Chittora, program manager with charity Aajeevika Bureau, which works on migrant rights.

Skill centers run by Aajeevika Bureau have seen a rise in the number of migrant workers signing up for short-term courses, with bike-repairing proving the most popular.

Abhishek Chola, founder of job portal JustRojgar — a social enterprise — said that besides upskilling and reskilling, they also provide placement to their students and ensure they have proper offer letters and salary details in their contracts.

“The basic mission is to motivate candidates to improve their livelihood,” Chola said.

Mahadev mobile store in Rajsamand district of western Rajasthan State opened for business last week.

Store owner Ganesh Meghwal, 23, was working in a scrap shop in neighboring Gujarat State when the lockdown was announced in March. He lost his job and after a month’s struggle to survive in Jamnagar, he returned home.

“I was scared and worried about survival,” Meghwal said. “I had to quarantine for a month when I returned and then worked for sometime under the 100-day [rural work] scheme. Then I joined a mobile repair course and have now opened my shop.”

Meghwal borrowed money from his father and dipped into his small savings to start the shop. He hopes to recover the investment of 50,000 Indian rupees (US$679) within a few months.

“There aren’t many mobile stores here and I do everything, from repairing phones to recharging cards, helping people pay bills and selling accessories,” Meghwal said.

“Now I’m trying to see if my wife can also do a skill course she is interested in. I’m trying to enroll her in a computer course, though she is more keen on tailoring. Once she is done, she can also get back to earning,” he said.

Saxena has just enrolled a new intake of workers on a four-month online electricians training course.

“The challenge is not just Internet connectivity, but also helping them switch their mindset,” Saxena said. “They have to switch off from being employees and start

Stephen Garrett, a 27-year-old graduate student, always thought he would study in China, but first the country’s restrictive COVID-19 policies made it nearly impossible and now he has other concerns. The cost is one deterrent, but Garrett is more worried about restrictions on academic freedom and the personal risk of being stranded in China. He is not alone. Only about 700 American students are studying at Chinese universities, down from a peak of nearly 25,000 a decade ago, while there are nearly 300,000 Chinese students at US schools. Some young Americans are discouraged from investing their time in China by what they see

MAJOR DROP: CEO Tim Cook, who is visiting Hanoi, pledged the firm was committed to Vietnam after its smartphone shipments declined 9.6% annually in the first quarter Apple Inc yesterday said it would increase spending on suppliers in Vietnam, a key production hub, as CEO Tim Cook arrived in the country for a two-day visit. The iPhone maker announced the news in a statement on its Web site, but gave no details of how much it would spend or where the money would go. Cook is expected to meet programmers, content creators and students during his visit, online newspaper VnExpress reported. The visit comes as US President Joe Biden’s administration seeks to ramp up Vietnam’s role in the global tech supply chain to reduce the US’ dependence on China. Images on

New apartments in Taiwan’s major cities are getting smaller, while old apartments are increasingly occupied by older people, many of whom live alone, government data showed. The phenomenon has to do with sharpening unaffordable property prices and an aging population, property brokers said. Apartments with one bedroom that are two years old or older have gained a noticeable presence in the nation’s six special municipalities as well as Hsinchu county and city in the past five years, Evertrust Rehouse Co (永慶房產集團) found, citing data from the government’s real-price transaction platform. In Taipei, apartments with one bedroom accounted for 19 percent of deals last

US CONSCULTANT: The US Department of Commerce’s Ursula Burns is a rarely seen US government consultant to be put forward to sit on the board, nominated as an independent director Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電), the world’s largest contract chipmaker, yesterday nominated 10 candidates for its new board of directors, including Ursula Burns from the US Department of Commerce. It is rare that TSMC has nominated a US government consultant to sit on its board. Burns was nominated as one of seven independent directors. She is vice chair of the department’s Advisory Council on Supply Chain Competitiveness. Burns is to stand for election at TSMC’s annual shareholders’ meeting on June 4 along with the rest of the candidates. TSMC chairman Mark Liu (劉德音) was not on the list after in December last