Sitting in his office in Bhutan’s sleepy capital, newspaper editor Tenzing Lamsang muses on the dramatic impact of cellphone technology on a remote Himalayan kingdom known as the “last Shangri-La.”

“Bhutan is jumping from the feudal age to the modern age,” said Lamsang, editor of the Bhutanese biweekly and online journal. “It’s bypassing the industrial age.”

As the last country in the world to get television and one that measures its performance with a “Gross National Happiness” yardstick, Bhutan might have been expected to be a hold-out against mobile technology.

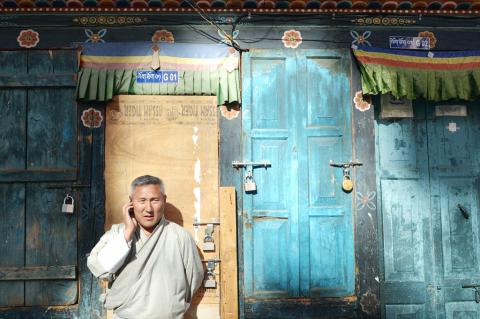

Photo: AFP

While monks clad in traditional saffron robes remain a common sight on the streets of the capital Thimpu, they now have to dodge cellphone users whose eyes are glued to their screens.

It has a largely rural population of just 750,000, but Bhutan’s two cellular networks have 550,000 subscribers. And the last official figures, in 2012, showed more than 120,000 Bhutanese had some kind of mobile Internet connectivity.

Wedged between China and India, the sparsely populated “Land of the Thunder Dragon” only got its first television sets in 1999, at a time when less than one-quarter of households had electricity.

Thanks to a massive investment in hydropower in the following decade and a half, nearly every household is now hooked up to the electricity grid.

The radical change in lifestyle has coincided with an equally dramatic transformation of the political system, with the monarchy ceding absolute power and allowing democratic elections in 2008.

The second nationwide elections took place last year, bringing Bhutanese Prime Minister Tshering Tobgay, a charismatic former civil servant, into office.

In a recent interview, Tobgay underlined how he regarded technology as a force for good and not something to be resisted.

“Technology is not destructive. It’s good and can contribute to prosperity for Bhutan,” the prime minister said. “Cellular phones became a reality 10 years ago. We adopted it very well, almost everybody has a cellular phone, that’s the reality.”

The prime minister’s own Facebook page has more than 25,000 followers who can get updates on everything from his talks with Myanmar opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi to photographs of Bhutan police recruits in training.

Lamsang says social media had “a largely positive role” to play in the fledgling democracy as a way of raising awareness in government circles about a range of issues.

He said there were now 80,000 Facebook users and the number was rising by the day.

“That gives you an idea of how popular the Internet has become in such a short time, he said.

As the number of households with Internet connections remain limited, Bhutan has seen a proliferation of cybercafes.

Jigme Tamang, an employee at Norling Cyber World in Thimpu, says the best time of year for business comes when students need to check their examination results and then register online for courses.

“We are a little bit worried about the rise of smartphones, because if people can connect through them they will not come here to use our system,” he said.

Eighteen-year-old Suraj Biswa said his smartphone was a fundamental part of his life.

“With my smartphone linked to the Internet, I can use Facebook and various software for editing photos,” said Biswa, a high -school student from Samtse in southern Bhutan. “I use Facebook to exchange with friends or relatives abroad. For example, I have cousins in Nepal — without Internet and Facebook, I cannot communicate with them.”

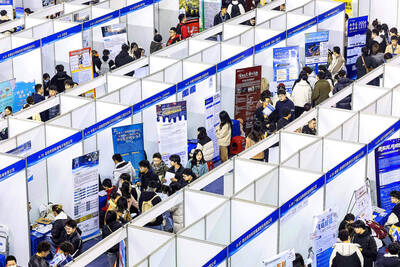

Stephen Garrett, a 27-year-old graduate student, always thought he would study in China, but first the country’s restrictive COVID-19 policies made it nearly impossible and now he has other concerns. The cost is one deterrent, but Garrett is more worried about restrictions on academic freedom and the personal risk of being stranded in China. He is not alone. Only about 700 American students are studying at Chinese universities, down from a peak of nearly 25,000 a decade ago, while there are nearly 300,000 Chinese students at US schools. Some young Americans are discouraged from investing their time in China by what they see

MAJOR DROP: CEO Tim Cook, who is visiting Hanoi, pledged the firm was committed to Vietnam after its smartphone shipments declined 9.6% annually in the first quarter Apple Inc yesterday said it would increase spending on suppliers in Vietnam, a key production hub, as CEO Tim Cook arrived in the country for a two-day visit. The iPhone maker announced the news in a statement on its Web site, but gave no details of how much it would spend or where the money would go. Cook is expected to meet programmers, content creators and students during his visit, online newspaper VnExpress reported. The visit comes as US President Joe Biden’s administration seeks to ramp up Vietnam’s role in the global tech supply chain to reduce the US’ dependence on China. Images on

New apartments in Taiwan’s major cities are getting smaller, while old apartments are increasingly occupied by older people, many of whom live alone, government data showed. The phenomenon has to do with sharpening unaffordable property prices and an aging population, property brokers said. Apartments with one bedroom that are two years old or older have gained a noticeable presence in the nation’s six special municipalities as well as Hsinchu county and city in the past five years, Evertrust Rehouse Co (永慶房產集團) found, citing data from the government’s real-price transaction platform. In Taipei, apartments with one bedroom accounted for 19 percent of deals last

US CONSCULTANT: The US Department of Commerce’s Ursula Burns is a rarely seen US government consultant to be put forward to sit on the board, nominated as an independent director Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電), the world’s largest contract chipmaker, yesterday nominated 10 candidates for its new board of directors, including Ursula Burns from the US Department of Commerce. It is rare that TSMC has nominated a US government consultant to sit on its board. Burns was nominated as one of seven independent directors. She is vice chair of the department’s Advisory Council on Supply Chain Competitiveness. Burns is to stand for election at TSMC’s annual shareholders’ meeting on June 4 along with the rest of the candidates. TSMC chairman Mark Liu (劉德音) was not on the list after in December last