Sometimes the acknowledgements appended to a book can feel distinctly intimidating. The author of Queer Marxism in Two Chinas, Petrus Liu (劉奕德), states, for example, that portions of his book were given as talks in no fewer than 16 universities, and that some of the material appeared earlier in four academic journals. A reviewer for a family newspaper such as the Taipei Times may naturally wonder whether such a text can be presented without appropriate reverence in the face of such apparent and widespread authentication.

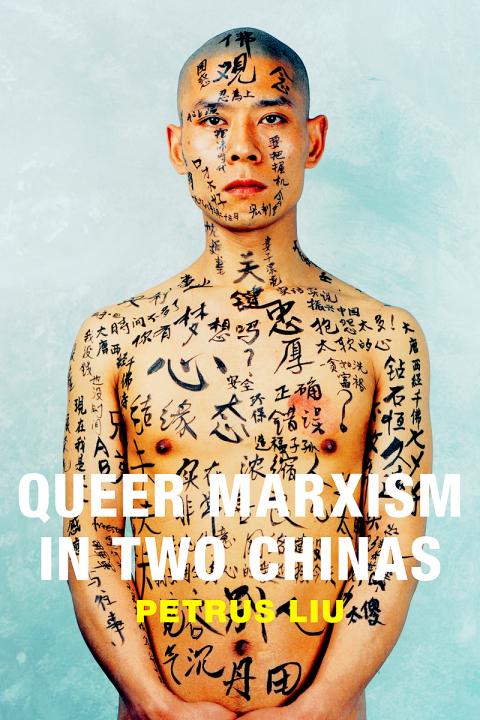

But review it we must, because Taiwan forms the subject of well over half the text. There is another problem, however, and that is that this book is written in the context of the academic area known as “queer theory.” The practical result of this is that it contains terms the general reader may not be over-familiar with, such as “imaginary” used as a noun (all the dictionaries I’ve consulted give it only as an adjective), “cisnormative,” “alterity” and “desynchronizingation.” Non-academic readers in Taiwan, nonetheless, will no doubt be curious to know what a book with such a title, let alone such a cover image, contains, and so the following remarks are aimed in part at easing their discomfort.

The essence of what Liu argues is that “Queer Marxism” in Taiwan and China is not simply the US product imported into Asian universities. Instead, these two places have their own queer Marxist traditions and founding texts, and the US and European assumption that the relative freeing up of gay life in China today is a result of the disappearance of Marxism there is wide of the mark.

Of course, readers are likely to react with surprise to learn of Marxism of any kind in Taiwan. They would be wrong, argues Liu. In the KMT-dominated 1960s, he points out, a journal, Literature Quarterly (文學季刊), was founded in Taipei that was heavily influenced by Marxism, so much so that one of its leading lights, Chen Ying-zhen (陳映真), was sentenced to ten years in prison in 1968 for, among other things, participating in a reading group on Marx and Marxist authors. In addition, today Taiwan’s cultural queer theorists “adamantly refuse to let the official political identity of anticommunist Taiwan define them.”

As for individuals who represent this home-grown queer theory, significantly different from the Western variety, Liu concentrates on Cui Zien (崔子恩) in China (of whom more in a moment), and Josephine Ho (何春蕤) and Ding Naifei (丁乃非) in Taiwan. All three set their sights against the focus in US culture on gay life being little different from the heterosexual form, and being happily focused on domesticity and consumption. “My gay lifestyle? Eat, sleep, go to work, pay taxes,” as a popular T-shirt had it on a Pride March in San Francisco.

Instead, these three iconic academics here in Asia all prefer to look at sexual outsiders for whom gay marriage, for instance, holds little attraction. What about these people, they ask. Aren’t sex workers, people with HIV/AIDS, and lovers of sexual variety in general, human too, and with rights?

Cui claims to be China’s only openly gay academic. He’s a professor at the Beijing Film Academy, but without any teaching assignments. He makes improvized, unscripted films featuring transvestites, dinosaurs, reptiles and extra-terrestrials, all beings he considers “queer” in that they live at some remove from conventional society. His attempt to found China’s first gay pride march in 2005 was blocked by the authorities. His purpose in producing his films, he once said, was to “destroy the respectability of gays.” He is therefore the last person to want to import US “queer theory” into Asia.

So what does a Chinese version of “queer theory”, whether in Taiwan or in China, look like? Here Liu has to fall back on what could be thought of as over-familiar literary examples — Pai Hsien-yung’s (白先勇) Crystal Boys (孽子), Chen Ruoxi’s (陳若曦) Paper Marriage (紙婚), which was filmed by Ang Lee (李安) in 1993 as The Wedding Banquet, and Xiao Sa’s (蕭颯) Song of Dreams (如夢令), all three first published in Taiwan, plus a few others. Liu has to lean over backwards to make the last of these fit into his queer discourse; it’s the story of a straight woman, after all, and has only one minor gay male character.

For a while I was unsure what to make of this book, but my eyes were opened when I saw Liu described in the post-Sunflower movement online publication New Bloom (破土) as a member of “the pro-unification left”. This, if true, would explain why, despite so much of his material coming from Taiwan, he has a section close to the book’s end on “Queer Illiberalism in Taiwan” in which he states: “While rhetorically endorsing human rights, the Taiwanese state regularly mobilizes the police to raid gay parties and harass gay bars.” Unfortunately, of the four instances he cites, the most recent comes from 12 years ago. This hardly adds up to “illiberalism” of any kind in contemporary Taiwanese society.

Elsewhere he writes: “In fact, the rhetoric of tolerance, liberalism, and progress is a political ruse designed to win over the sympathy of the American public, since Taiwan’s continuous de facto and imagined future de jure status as a sovereign nation-state depends on American military protection and support.”

This may be the reason why Liu, who is an associate professor at the Yale-NUS College in Singapore, is in places less than fully enthusiastic about Taiwan’s gay scene, and certainly about what he calls “the Taiwanese independence project,” despite his admission that Taiwan has created “a greater civic space” than anywhere else in the region for gay concerns in general.

Queer Marxism in Two Chinas, then, is a comprehensive but fundamentally paradoxical book that may end up flattering and infuriating Taiwanese readers in approximately equal measure.

In late October of 1873 the government of Japan decided against sending a military expedition to Korea to force that nation to open trade relations. Across the government supporters of the expedition resigned immediately. The spectacle of revolt by disaffected samurai began to loom over Japanese politics. In January of 1874 disaffected samurai attacked a senior minister in Tokyo. A month later, a group of pro-Korea expedition and anti-foreign elements from Saga prefecture in Kyushu revolted, driven in part by high food prices stemming from poor harvests. Their leader, according to Edward Drea’s classic Japan’s Imperial Army, was a samurai

Located down a sideroad in old Wanhua District (萬華區), Waley Art (水谷藝術) has an established reputation for curating some of the more provocative indie art exhibitions in Taipei. And this month is no exception. Beyond the innocuous facade of a shophouse, the full three stories of the gallery space (including the basement) have been taken over by photographs, installation videos and abstract images courtesy of two creatives who hail from the opposite ends of the earth, Taiwan’s Hsu Yi-ting (許懿婷) and Germany’s Benjamin Janzen. “In 2019, I had an art residency in Europe,” Hsu says. “I met Benjamin in the lobby

April 22 to April 28 The true identity of the mastermind behind the Demon Gang (魔鬼黨) was undoubtedly on the minds of countless schoolchildren in late 1958. In the days leading up to the big reveal, more than 10,000 guesses were sent to Ta Hwa Publishing Co (大華文化社) for a chance to win prizes. The smash success of the comic series Great Battle Against the Demon Gang (大戰魔鬼黨) came as a surprise to author Yeh Hung-chia (葉宏甲), who had long given up on his dream after being jailed for 10 months in 1947 over political cartoons. Protagonist

A fossil jawbone found by a British girl and her father on a beach in Somerset, England belongs to a gigantic marine reptile dating to 202 million years ago that appears to have been among the largest animals ever on Earth. Researchers said on Wednesday the bone, called a surangular, was from a type of ocean-going reptile called an ichthyosaur. Based on its dimensions compared to the same bone in closely related ichthyosaurs, the researchers estimated that the Triassic Period creature, which they named Ichthyotitan severnensis, was between 22-26 meters long. That would make it perhaps the largest-known marine reptile and would