“Don’t walk so fast, walk behind me and film my backpack,” says 11-year-old Zhang Zhechen (張澤晨), known as “Chang Chang” (晨晨), at the beginning of Chang Chang Going to School Overseas (晨晨跨海上學去). “You’re too close ... People say I look like Justin Bieber, but it’s not true … I’m the main character, of course I have to be awe-inspiring.”

This scene sets the tone for the rest of the film — it is natural and completely candid. Chang Chang appears to simply be himself, often interacting with the camera operator and making funny statements to the audience, who frequently burst out in laughter during the film’s Taipei screening on Wednesday.

More than once he tells the operator to stop shooting, and there is even a hilarious sequence where he declares his love to a female schoolmate and suggests that they should have a traditional Chinese wedding.

Photo Courtesy of Wu Shwu-mey

Indeed, Chang Chang’s larger-than-life personality drives the narrative, which was filmed over two years. Director Wu Shwu-mey (吳淑美), a Hsinchu University of Education special education professor, who shot most of the film, says that she was forced to include herself in the final cut because Chang Chang kept mentioning her name in the scenes.

“Otherwise people would be wondering, who is this Professor Wu?” she says.

Despite having no filmmaking background, this is Wu’s third documentary about children with disabilities, winning her a Bronze Remi at WorldFest Houston last year.

Photo Courtesy of Wu Shwu-mey

A native of China’s Zhengzhou (鄭州) in Henan Province, Chang Chang was having difficulties at school due to intellectual disabilities and behavioral issues. In the fifth grade, he came to Taiwan to attend an inclusive education school in Hsinchu run by Wu, where special needs and typical students study side by side. Usually, each class is about one-third special needs.

The camera follows him through his everyday life over two years, through the good times and the bad, telling Chang Chang’s story as a human being rather than a child with disabilities.

His exact disability is never mentioned in the film — a conscious decision by Wu, who wanted to let the narrative do the talking. Wu started shooting a few months after Chang Chang started attending school in Hsinchu, so there were no scenes of his previous behavior and how he was like in China, or even when he first arrived.

We do hear about his difficulties and the challenges of dealing with him from his parents, teachers, caretakers and former classmates, and watch his struggles and meltdowns in Taiwan — but the main focus appears to be how his behavior, performance and self-esteem improves as he finds his place in a more accepting environment. You almost forget that he has a disability at one point.

Over two years, Chang Chang visited Taiwan nine times — going back to China for holidays and other reasons as his mother was not able to be with him in Taiwan all the time. But the narrative does not get messy because of this disjointed timeline, even following him back home several times. It is well-organized and briskly paced, making full use of the 70 minutes of running time — it helps that Wu had Liao Ching-sung (廖慶松), best known for his long-time collaboration with Hou Hsiao-hsien (侯孝賢), as editing consultant.

But, as mentioned earlier, it is Chang Chang that captures the audience’s attention and keeps the story moving. It is more than the fact that he is simply hilarious. It is the compassion, the potential, the genuine humanity that exists in a person who was once deemed a lost cause by society and those around him. No drastic events, major conflicts or sharp social commentary actually take place in the film, but maybe that is not needed in every production.

Unfortunately, Wednesday was the only screening of this film in Taiwan due to limited finances, Wu says. It will be released in DVD format at the end of June.

In late October of 1873 the government of Japan decided against sending a military expedition to Korea to force that nation to open trade relations. Across the government supporters of the expedition resigned immediately. The spectacle of revolt by disaffected samurai began to loom over Japanese politics. In January of 1874 disaffected samurai attacked a senior minister in Tokyo. A month later, a group of pro-Korea expedition and anti-foreign elements from Saga prefecture in Kyushu revolted, driven in part by high food prices stemming from poor harvests. Their leader, according to Edward Drea’s classic Japan’s Imperial Army, was a samurai

The following three paragraphs are just some of what the local Chinese-language press is reporting on breathlessly and following every twist and turn with the eagerness of a soap opera fan. For many English-language readers, it probably comes across as incomprehensibly opaque, so bear with me briefly dear reader: To the surprise of many, former pop singer and Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) ex-lawmaker Yu Tien (余天) of the Taiwan Normal Country Promotion Association (TNCPA) at the last minute dropped out of the running for committee chair of the DPP’s New Taipei City chapter, paving the way for DPP legislator Su

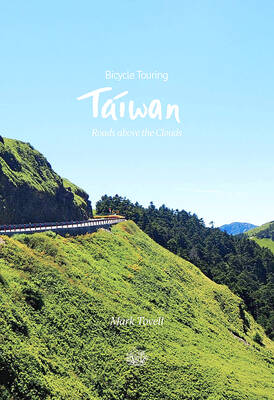

It’s hard to know where to begin with Mark Tovell’s Taiwan: Roads Above the Clouds. Having published a travelogue myself, as well as having contributed to several guidebooks, at first glance Tovell’s book appears to inhabit a middle ground — the kind of hard-to-sell nowheresville publishers detest. Leaf through the pages and you’ll find them suffuse with the purple prose best associated with travel literature: “When the sun is low on a warm, clear morning, and with the heat already rising, we stand at the riverside bike path leading south from Sanxia’s old cobble streets.” Hardly the stuff of your

Located down a sideroad in old Wanhua District (萬華區), Waley Art (水谷藝術) has an established reputation for curating some of the more provocative indie art exhibitions in Taipei. And this month is no exception. Beyond the innocuous facade of a shophouse, the full three stories of the gallery space (including the basement) have been taken over by photographs, installation videos and abstract images courtesy of two creatives who hail from the opposite ends of the earth, Taiwan’s Hsu Yi-ting (許懿婷) and Germany’s Benjamin Janzen. “In 2019, I had an art residency in Europe,” Hsu says. “I met Benjamin in the lobby